Ferrari Beyond Enzo

Atlas F1 Magazine Writer

Wrapping up his four-part feature on the life and times of Enzo Ferrari, Atlas F1's David Cameron looks at the team the Old Man left behind, and how a group of men have taken the Ferrari name to levels of success that not even Enzo himself had dreamt of

Ferrari is the most common name in the Modena region, but Enzo made it synonymous with quality, made it famous worldwide. This fame will never fade now, even if the paint on his childhood house does. The team that Enzo built is now preparing to challenge for a consecutive fifth Constructors Championship and fourth World Drivers Championship, and they are in a very strong position to achieve that. This type of success in unprecedented, either by the Scuderia or any other team - it's the stuff that legends are built of.

Why has Ferrari managed to grow in stature when a team like Lotus fell away and died? They were comparable teams - both formed almost single-handedly by a charismatic personality out of nothing, both had a lot of success on the track, both formed companies to produce high end road cars. The differences were the people who took over, and that age-old necessity for success in Formula One - money.

Towards the end of his life Enzo took less and less interest in his creation, and the levels of political chicanery, always high, were astonishing even for the Scuderia. The old man didn't care - he was waiting to die. Agnelli cared, though, as Ferrari have always eschewed advertising in favour of promotion via racing, and when the racing team suffered so did the sales. Agnelli always looked at the bottom line; what he needed was a strong personality to grab the team and pull it into order around him, much as Enzo had done in the old days before he stopped caring. Enzo wanted his son Piero to take an active role, but his personality was never as strong as the old man's, and he would never be a suitable replacement.

Luca di Montezemolo had always been a favourite of Agnelli, and the younger man looked at him as almost a father. He had studied with members of the Agnelli clan, the de facto royal family of Italy, and had come to their attention early. It is said that his appointment as direttore sportivo of Ferrari in June 1973 was as a result of a request from Agnelli to Enzo (who had nonetheless been impressed with the young man himself), and the success that came from his time with the team speaks for itself: two drivers championships and three constructors championships during his stint with the team.

When he left the team in 1977 it was not for the usual reason in the paddock - to move to another team - but rather to progress in business. He had always seemed different to the other men in Formula One; he dressed better, he was educated and refined; and his future was always going to be different to them.

In November 1991, di Montezemolo was brought back home to Ferrari, at the request of Agnelli, to replace the carousel of managers who had gone through the company since the old man's death. The team was foundering without a suitable captain, and the company was losing value. For the first time since Fiat had taken over in 1969 the whole operation at Ferrari was going to be under the control of one man - di Montezemolo. He was charged with improving sales, and he knew that the way to do that was by improving the racing team, and he made moves to do this. Alain Prost had already left the team, horrified at the depths they had sunk to, and they were forced to rely on Jean Alesi, a fast but erratic young driver who had no experience of being a senior driver. Ivan Capelli was brought in to partner him, as none of the recognised top line drivers would come near the team.

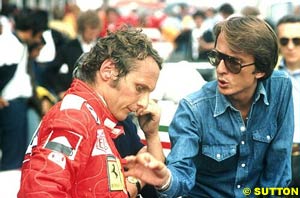

His first attempt to put the Scuderia back on top was an acknowledgement of his past. Di Montezemolo brought Harvey Postlethwaite back, the first man to create a carbon fibre chassis for the team, to organise the technical organisation; Niki Lauda was hired to help with the drivers and their mechanics; and John Barnard was returned as the chief designer. It was an abject failure - 1992 was a bad time to be in anything other than the all-conquering Williams FW14B, and the Scuderia failed to take any wins, poles, or fastest laps. The season was so bad that the high points were two lucky third place finishes for Alesi. Di Montezemolo needed a new team manager, as the work of running both the team and the manufacturing division was too much for one man.

Jean Todt was making a name for himself in the Rally world, first as a driver then as team manager. He won races as a co-driver and championships as a team boss, conquered Le Mans, Paris-Dakar and sportscar championships. By 1992, Formula One was the one remaining motorsport challenge for him. Di Montezemolo had seen Todt's success, and he was impressed. He made an approach to gauge his interest in joining the Scuderia, and the timing was perfect. Todt joined Ferrari in July 1993 and the train was in motion. Less than two years later, they would sign the driver who will become the biggest star and most successful driver of his generation.

Many people have subsequently wondered what Enzo would have made of the German, and there's no doubt that he would have disapproved of the pay packet that came with the deal - Enzo never pulled out his wallet if he could avoid it. That said, he brought champions to the team in times of turmoil - he brought Juan-Manuel Fangio onboard despite the obvious antipathy between the two - and he paid over the odds if he had no other choice - the ebreo contract with Lauda is proof of that. The old man would have been a party to bringing Schumacher to the Scuderia if he had been alive - he would have complained, but that was his default setting anyway, so that wouldn't be a surprise.

Agnelli came to the Ferrari launch in 1996, the first time he had ever done so. When asked why they had paid so much money for Schumacher he replied: "he is the best driver in the world - if we do not succeed now we will know it is our fault."

The year after, and on Schumacher's recommendation, Ross Brawn was brought on as technical director from Benetton, and Brawn immediately hired Rory Byrne from his old team as chief designer. The pair joined Paolo Martinelli, a young Modenese engineer who had joined the company fresh from Bologna University and was promoted in the mid-1990s to head of the engine department, a reflection of Mauro Forghieri all those years ago.

This is the biggest change at the Scuderia since the days of Enzo - political chicanery is a thing of the past, something Jean Todt himself once stated was his biggest achievement at the Scuderia, and the employees work to one overall goal, rather than their own. The only parallel in the history of the team is the period from 1973 to 1977, which not coincidentally was the period when di Montezemolo ran the team. The difference now, though, is that it seems much less likely that the team (or the company) can be as seriously derailed as it was from time to time under the old man.

Some people feel that Enzo Ferrari invented modern racing, and in many ways he did - he was the first to obtain trade credit from auto industry companies, among the first to run sponsorship on a car (the Fernet Branca deal at the Temporada series), and the first to set up a production company, among his initiatives. But inventors don't often perfect their creation, and this is where the new personalities come in - if Enzo Ferrari invented motor racing, then di Montezemolo and his men are now perfecting success. The difference is that it takes more men to succeed now than it did in the days of the old man. Maybe it's harder than it once was, or maybe Ferrari was just different - legends don't grow from nothing.

"His (father's) workshops, and the family house, were sited at 264 via Camurri, next to the railway line running through the northern end of town... The buildings stand there today, now renamed and renumbered but looking almost as they did then, except for the television aerials sprouting from the roof of the two-storey house. From the road, the house looks deserted, the long, low workshops disused. But round the side, where the railway track passes along the front, up there on the brickwork of the upper floor of the house, the name FERRARI can just be seen, carefully lettered in white paint that may be only a decade or two from fading completely." - Enzo Ferrari, A Life by Richard Williams.

Ferrari launched their new Formula One challenger on 7 February at Maranello, naming it the F2003-GA in honour of Gianni Agnelli, the chairman of Fiat Group who had recently passed away at the age of 81. This was an extraordinary honour - no racing car from the Scuderia had borne the name of any man since the Dino in 1957. The honour was not misplaced, as without Agnelli it is safe to say that the Ferrari name, and the team which bore it, would have faded away like Lotus.

Ferrari launched their new Formula One challenger on 7 February at Maranello, naming it the F2003-GA in honour of Gianni Agnelli, the chairman of Fiat Group who had recently passed away at the age of 81. This was an extraordinary honour - no racing car from the Scuderia had borne the name of any man since the Dino in 1957. The honour was not misplaced, as without Agnelli it is safe to say that the Ferrari name, and the team which bore it, would have faded away like Lotus.

After Ferrari, he had many jobs throughout the Fiat empire, where he was the youngest senior manager in the history of the company - he ran the publishing company Itedi (home of the daily newspaper La Stampa) and the drinks company Cinzano, for example - although he never worked at Fiat Auto, which most thought was the obvious next step after Ferrari. He spent time running the first Italian America's Cup challenge, Azzurra, and was the general manager of the organizing committee for Italia 90, the football World Cup held that year, as well as the football team Juventus. Di Montezemolo was a man who succeeded at everything he did, and who had a clear distaste for being bored.

After Ferrari, he had many jobs throughout the Fiat empire, where he was the youngest senior manager in the history of the company - he ran the publishing company Itedi (home of the daily newspaper La Stampa) and the drinks company Cinzano, for example - although he never worked at Fiat Auto, which most thought was the obvious next step after Ferrari. He spent time running the first Italian America's Cup challenge, Azzurra, and was the general manager of the organizing committee for Italia 90, the football World Cup held that year, as well as the football team Juventus. Di Montezemolo was a man who succeeded at everything he did, and who had a clear distaste for being bored.

Michael Schumacher won the 1994 World Championship in controversial manner, but he then went on to win the 1995 Championship in relative ease. It was obvious to all he was a truly talented driver, and despite remaining a controversial figure he was also gaining significant public support. To a large extent, he was exactly what Ferrari needed. And they got him - for the biggest contract signed with any driver in Formula One: $25 million a year, his salary sponsored by a coalition of Marlboro, Shell and Fiat.

Michael Schumacher won the 1994 World Championship in controversial manner, but he then went on to win the 1995 Championship in relative ease. It was obvious to all he was a truly talented driver, and despite remaining a controversial figure he was also gaining significant public support. To a large extent, he was exactly what Ferrari needed. And they got him - for the biggest contract signed with any driver in Formula One: $25 million a year, his salary sponsored by a coalition of Marlboro, Shell and Fiat.

How successful is the new Ferrari, under di Montezemolo's reign, and with Todt, Martinelli, Schumacher, Brawn and Bryne? The statistics speak for themselves, with unprecedented streak of four Constructors' Championships and three World Drivers' Championships. Records trashed one by one - most wins in a season, most points in a season, or poles, or fastest laps. The first Drivers' Championship for the team in 21 years became the beginning of the most successful period in the Scuderia's history.

How successful is the new Ferrari, under di Montezemolo's reign, and with Todt, Martinelli, Schumacher, Brawn and Bryne? The statistics speak for themselves, with unprecedented streak of four Constructors' Championships and three World Drivers' Championships. Records trashed one by one - most wins in a season, most points in a season, or poles, or fastest laps. The first Drivers' Championship for the team in 21 years became the beginning of the most successful period in the Scuderia's history.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 9

Articles

Montoya & Williams: Can They Challenge?

Reflections on Mosley's Brave New World

Pencils at Dawn

The Cult of a Personality, IV

2003 Season Preview

2003 Drivers Preview

2003 Teams Preview

2003 Technical Preview

The 2003 Atlas F1 Gamble

Columns

Off-Season Strokes

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |