The Life and Times of Enzo Ferrari

Atlas F1 Magazine Writer

75 years after he founded the Societa Anonima Scuderia Ferrari, Enzo Ferrari's dream of dominating motor racing is very much a reality - as the team launches its 2003 Formula One challenger in preparation for an unprecedented consecutive fifth Constructors' Championship and fourth World Drivers Championship. This success wouldn't have come about had it not been for the Old Man himself; but in all likelihood, the team would never have been as successful as it is now, had Enzo still been around. In a special four-part feature, Atlas F1's David Cameron reviews Enzo Ferrari's life and times, and beyond

He was known to many, and by many different names - some called him ingegnere, although he never studied engineering (he was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Bologna when he was in his sixties). Others knew him as commendatore, although the man himself thought it a fascist title. Many referred to him as The Old Man. Still others called him il drake - the dragon - while his mother merely called him Enzo. The man himself, though, referred to himself simply as Ferrari.

The name Ferrari is now synonymous with the racing team he started, the team that wouldn't exist today if he hadn't been there pushing and fighting for its existence. The last four World Constructors Championships and three World Drivers Championships are ample evidence of the merits of the team he left behind. But it is equally fair to say that the success the team enjoys today wouldn't have happened with the old man in control, a man who seemed entranced by the politics inherent in the team under him, a man who, while all who worked under him agreed that he controlled the team with an iron fist, seemed unwilling to eradicate the very forces that mitigated against him succeeding - the infighting entrenched under his watch.

In 1916, a year after Italy joined the First World War, the elder Alfredo contracted bronchitis, suffering with it for a small time before dying of the illness. Shortly afterwards Dino, who had joined the Air Force a year before, died in a sanatorium on the front of an unknown illness. Enzo, who felt desperately alone after these tragedies, received his call up papers the following year, and was given the job of shoeing the mules that were used to move field guns in the mountains. Within months he too fell ill, and only two operations prevented the family line dying with him. Many years later, with the rich and famous flocking to Modena to buy his cars, his mother was often heard to cry the better of my sons is dead. Presumably she didn't spend much time reading child rearing handbooks.

After the war, and with the family business finished due to his father's death, Ferrari traveled to Torino with - as he wrote in his memoirs Le mie gioie terribili (My Terrible Joys) - "no money, no experience, limited education. All I had was a passion to get somewhere." He initially approached the car making giant Fiat but was turned down, the personnel manager stating that they didn't have jobs for every ex-serviceman in Italy. Living off a small inheritance he took a room near the main station and was eventually offered a job at Costruzioni Meccaniche Nazionali (CMN), which were changing from the manufacture of tractors during the war to assembling passenger cars from spare parts, on the recommendation of a friend of his. He spent a lot of time testing the company's product, which awoke his enthusiasm for motor racing, leading him to pursue his dream of being a racer, using their cars.

Ferrari's first recorded race was in October 1919 at a hillclimb known as the Parma-Poggia di Berceto, driving a 2.3 litre CMN Tipo bought at a discount from the company. He set off many hours after the first driver started, and his efforts brought him home 12th overall, and 5th in his class. It was an inauspicious start, but enough to convince himself that he had a future in motor racing. To this end he decided that he would attempt the Targa Florio, a famous event run through the narrow, twisting streets of Sicily. In those days it was quite an achievement to even reach the course, let alone compete, given the poor state of the roads of Italy.

But arrive he did, after allegedly driving through a blizzard and scaring off a gang of wolves with a pistol he kept under the driver's seat, to find a 108 km 'circuit' that was entirely made up of public roads which, at any time, could see local peasants walking across the road, entirely unaware of what was about to scream around the corner.

On his first lap Ferrari was delayed by a loose petrol tank, which took 40 minutes to repair, relegating him to last place. On the final lap he was flagged down by 3 policemen who explained that the new president of Italy was making a speech in the piazza of the village ahead of them. Ferrari and his mechanic sat, with increasing agitation, as the long-winded politician spouted forth, only to be stuck behind the official procession for many miles after he finished. By the time Ferrari arrived at the finish line the race officials were long gone, with only a policeman there to record the times of all those who finished outside of the official cut off time of 10 hours.

Ferrari, furious, stormed into the race headquarters in Palermo and demanded that he be installed as an official finisher, and after a lengthy onslaught he was listed as finishing in ninth, and last, place. However, many years later a newspaper reported that the President was not in the village (Campofelice) on the day of the race, but actually in Termini Imerese, approximately 20km away and not on the actual circuit. This is not the only time that Ferrari's stories don't entirely match up with recorded history. Although he may not have approved of memorials, he certainly had no problem with myth making, even adding to the process himself on occasion.

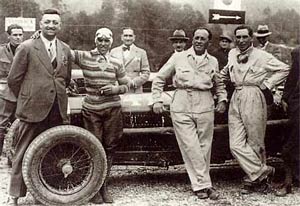

Around this time he split with CMN, picking up a 7 litre Isotta Fraschini for the 1920 Parma-Poggia di Berceto, which he steered to second place behind the opera singer Giuseppe Campari, with whom he became close friends. After some minor races Ferrari was signed as a junior driver for the Alfa Romeo team, becoming Campari's teammate, and at the next Targa Florio Ferrari's drive brought the team second place overall and first in their class, a significant result for the young team and for Ferrari himself. The result drew the attention of Antonio Ascari, already a notable driver on the Italian scene, and he later signed to the team himself.

Ferrari had to wait until 1923 for his first race win, at the Circuito di Savio, held on roads outside of Ravenna. At the finish Ferrari and his mechanic were carried over the heads of the crowd, and Ferrari wrote that on that day he returned to Modena to be introduced to Count Enrico Baracca, whose son had fought and died in the air squadron in which Ferrari's elder brother Dino had also served, and that the Countess instructed him to henceforth put the prancing horse of her son on his car for luck. "I still keep the photograph of Baracca with the dedication by the parents in which they entrusted me with the emblem," Ferrari wrote in his memoirs. "The horse was, and has remained, black, but I myself added the yellow background, this being the colour of Modena."

There are many question marks about this meeting, especially as the cavallino rampante has become such a powerful symbol of the company Ferrari later formed, and of the man himself. Some have suggested that the emblem did not belong to Baracca himself, but was the emblem of the entire squadron he fought for. Others state that the black horse is the symbol of the city of Stuttgart, and as such may have been attached to a plane shot down by the young fighter pilot, who later cut it from the remains of the fuselage, as was the habit of the times. In a way it's appropriate that there is such doubt about the origins of something so integral to the myth of the man, although in any event it was not until 1932 that Ferrari attached the shield to one of his cars.

It was 1921 when Ferrari met Laura Domenica Garello, a girl two years younger than himself from a village near Torino, who he described as una donna buffa - a funny girl. Around this time Ferrari seemed to be taking an increasing interest in the management of Alfa's racing team, persuading mechanics and other drivers to join, even if it meant that he was knocked down the pecking order in the driving roster.

The couple were married in April 1923, beginning a prolonged period of acrimony between wife and mother in law, both women fighting for the attention of Ferrari who seemed unable to ever achieve any sort of peace between the two, and who in any case was to remain seemingly more interested in his work. Ferrari had opened a business preparing and selling Alfa Romeos in Modena for the rich enthusiasts of the region, and it probably gave him respite from the bickering of the two women in his life.

In 1923 Ferrari spent little time in the cockpit of the Alfas, painted in the blood red of Italy - a colour which is said to have originated from the colour of the coats worn by the soldiers who fought with Garibaldi the previous century. It is unclear whether this was the idea of the team or of Ferrari himself, but the cars were good enough to bring success in the hands of Ascari and Campari, who between them won in Cremona, the Grand Prix of Europe, and led a clean sweep of four Alfas at the Italian Grand Prix in Monza.

The following year Ferrari raced only five times, winning three of them, in Savio (ahead of Tazio Nuvolari, just beginning his car racing career after switching from motorbikes), Polesine and Pescara. The latter was a major race, and the win came despite Ferrari starting in a car markedly inferior to the P2 Campari was driving, which meant he held no great expectations prior to the race.

From the start he was able to open a lead on the other drivers due to a large weight benefit, but he spent much of the race looking over his shoulder for his more fancied teammate, whose car had suffered mechanical problems and had accordingly pulled into a side street, so that the opposition would not realise he was missing until it was too late. This was probably Ferrari's introduction to team tactics.

This success led to Ferrari's potential big break - the team invited him to race with the new P2, alongside Ascari and Campari, at the forthcoming French Grand Prix. Ferrari arrived in Lyon with the team, and his memoirs state that "after the practice, which went well, I felt completely shattered. It made me so ill that I had to withdraw from the race."

Subsequent comments by Ferrari, as well as theories put forward from many quarters, seem to contradict themselves as to the actual cause of these strange actions, but it seems most likely that Ferrari suffered a form of mental breakdown. And, apart from a few minor races, this was effectively the end of his career in a car, and from that time on he devoted himself almost entirely to his business of preparing and selling cars, as well as moving into a management role in the Alfa Romeo racing team.

During this period Ferrari expanded his dealership to take in the Emilia Romagna region, opening a new office in Bologna. On a national stage the fascist dictatorship of Benito Mussolini was strengthening. Ferrari claimed to never take much of an interest in such things, although he was astute enough to realise that taking membership in the party would not harm his flourishing business, given the interests of his clientele. He was certainly not alone in this regard, with the owners of most businesses of the time doing likewise.

Alfa's racing team welcomed 1925 with a successful car, and a mood among the drivers and mechanics to match. This ebullient mood was shattered at the French Grand Prix in Linas-Montlhery when, while leading the race and looking for his third success in a row, the P2 of Ascari was pitched into a gruesome series of somersaults, resulting in his almost instant death. Ferrari, who modeled his business and racing career largely on the man, was devastated. At the funeral in Milan, it is said, Campari picked up the dead man's young son Alberto and told him "some day you will arrive at the heights, like he did. Perhaps you will be even more famous." (Which, while prescient, seems a little too quoteworthy to be likely.)

Ferrari tried to persuade the team to pick up Nuvolari at this stage, but in a test session to establish his worth he overdrove the P2, running off and rolling to the bottom of a slope, ending up entwined in a barbed wire fence. He didn't get the drive. Gaston Brilli-Perri did, taking victory at the Italian Grand Prix and the World Championship with it, after which Alfa Romeo announced their withdrawal from the Grand Prix circuit.

Ferrari lobbied hard and gained control of the management of the team and, when the inaugural Mille Miglia (thousand mile) race was run in 1927, he entered 3 cars to compete. Brilli-Perri set the initial running, but eventually each of the Alfas was to fall by the way. Nonetheless, the new race had captured the imagination of racing fans around the country and, eventually, around the world.

Nuvolari, shunned by the Alfa team, formed his own scuderia with five Bugattis purchased from the proceeds of racing. He was not alone, as many others were starting their own teams at the time. Ferrari had seen many of the cars prepared in his dealership race to some success, and the obvious next stage was to start a team of his own.

At a dinner with some of his wealthy clients he proposed the creation of his team, the Societa Anonima Scuderia Ferrari, with the result that Alfredo Caniato and Mario Tadini, who were already racing cars purchased from Ferrari, put up 130,000 lire, with a further 50,000 from Ferrari himself and a small addition from another friend. How Ferrari managed to extract this amount from men already driving his cars is not recorded, although he was always a persuasive man.

The Alfa Romeo executives in charge of racing, who had grave concerns about their own abilities to run a team but knew the value of success in racing, were easily convinced by Ferrari that he would be able to carry out this role successfully, in conjunction with the factory team, and they provided a token sum to this end, along with the tyre manufacturer Pirelli, as well as supplying the cars.

Flush with success Ferrari approached the spark plug manufacturer Bosch and the Shell lubricant company for support, inadvertently beginning the practice of trade sponsorship for racing teams.

The scuderia set up base back in Modena and prepared for the 1930 Mille Miglia. Ferrari entered 6 cars, none of which were to see the finish line, in a dramatic race won by Nuvolari, who tailed Achille Varzi in the dark for many miles without his lights on, sweeping past him just before they arrived at Brescia, giving Varzi no chance to retaliate. Both drivers were to play a major part in Ferrari mythology in the years to come.

A week later Ferrari entered himself in the race at the Circuito di Alessandria, driving a 1750, finishing third and earning the team's first podium, with Campari joining the team later in the year to earn a further third place in Caserta. This success led to Alfa providing the team with the more powerful P2, for which Campari was expected to return to the factory team.

Ferrari, in a brilliant move, secured the services of Nuvolari to drive the powerful new vehicle. Nuvolari, whose driving abilities were never in doubt even if his business acumen was, rewarded the team with a hat trick of win in hill climb events. At the end-of-season dinner Ferrari noted that, from 22 races, his team had secured 8 victories and a number of other good placings - a magnificent debut in all. With the proceeds of this success Ferrari set up a new headquarters, on Viale Trento e Trieste, on which location the team was to remain until the war.

The following year Ferrari competed in his final race as a driver, at the age of 33 and with his wife pregnant, at the Circuito delle Tre Provincie, south of Bologna, in one of the new Alfa 8C Monzas. Nuvolari, competing in a smaller 1750, broke the throttle cable in a heavy landing after hitting a trough. For a lesser driver this would have been the end of the race, but Nuvolari took his mechanic's belt and instructed him to use it to run the throttle while he steered and used the brakes normally. Making up the time lost, and more besides, he won the race to the astonishment of all in attendance. Ferrari, second in the race in a superior car, realised that his time as a driver was over. He signed Piero Taruffi, another young motorbike racer, and retired from driving.

Dino Ferrari was born on February 19th 1932, named after his dead uncle and grandfather, suffering from the rare defect known as Duchene's Muscular Dystrophy. His parents never had another child, possibly because they learned that the illness was genetic. They were simple people, for all their success, and medical advice was not what it is now. Certainly the relationship between the two parents was strained from this time, although the open secret that Ferrari had taken up with Lina Lardi, a quiet, elegant local girl, couldn't have helped.

Ferrari increasingly spent time with Lardi, in a relationship that lasted for the rest of his life, but a divorce would have been unthinkable for the times. Lardi was also to provide him with another male heir some years later, although Ferrari refused to publicly acknowledge that he had fathered Piero until after his wife's death in 1978. While divorce was unthinkable, the shame that would be brought to his wife if Ferrari admitted the affair was equally so. In Italy, then and now, appearances are important. An example, possibly apocryphal, of working for appearances sake: the Ferrari engine tuners, working on a new model, played with the trumpets at length to achieve the right engine note, not for performance sake, but rather to be pleasing to the ear. It worked - the famous conductor Herbert von Karajan once told Ferrari that, when he drove his car, he heard a symphony.

Caniato decided the time was right to sell his shares in the company, and the buyer was Count Carlo Felice Trossi, an amateur driver who took the team's first win for the 1932 season in the Coppa Gallenga. For the Mille Miglia, Ferrari transported nine cars to the start in support of the 4 factory cars. The Alfa of Mario Borzacchini won, with Trossi and Scarfiotti following behind for the Scuderia's best result to date in the race.

The famous shield made its first appearance later that year at the 24-hour race in Spa, where the team took first and second places, and after which the team never raced without the emblem. The team received their first new P3 from Alfa later that year, to immediate effect, with Nuvolari winning the Coppa Acerbo easily.

The political situation in Italy was changing rapidly at the time, with Mussolini pushing into Africa and demanding more support from the large national industries. To this end Alfa Romeo was placed under a state protection order and requested to turn their focus to supplying vehicles for the expanding military. The factory announced their complete withdrawal from motor racing with immediate effect at the start of 1933. Ferrari, always quick to seize an opportunity, organised a meeting with senior executives at Alfa to persuade them to allow the scuderia to take over all of the factory team's activities. And, of course, the supply of new P3s, which had proven so successful. Despite all of his success in the previous three seasons the answer was no, and the beautiful cars were locked away in a warehouse.

Nuvolari, seeing the writing on the wall, signed a contract to race with immediate effect for Maserati, with predictable results. Ferrari was livid, but he managed to extract a deal whereby the Maserati Nuvolari was to drive in Spa would be entered by Scuderia Ferrari. Predictably he won, but later in the year Nuvolari announced he was leaving for good, taking his mechanic, and teammates Borzacchini and Taruffi with him to Maserati. Ferrari, in desperation, turned to his friend Mario Lombardini from Pirelli to intercede on his behalf with Alfa to obtain the P3s. The deal was done, albeit for a hefty price, and the team was saved.

With his driving force depleted Ferrari turned to his old friend Campari, who came out of retirement for him, and he signed Luigi Fagioli and Louis Chiron. The scuderia was back in business, celebrating wins at the Coppa Acerbo, and the Comminges and Marseilles Grand Prix. The Italian Grand Prix at Monza was another success for Fagioli before tragedy struck on the banked track that afternoon for the Monza Grand Prix, when a four-car crash resulted in the deaths of Campari and Borzacchini. Ferrari mourned the death of his great friend Campari, and the scuderia had suffered their first fatal loss.

For the 1934 season Fagioli left to join Mercedes Benz and the test driver Eugenio Siena decided to form his own team. However, Alfa Romeo confirmed that the scuderia was to represent their interests in racing, recommending two young Algerian drivers, Marcel Lehoux and Guy Moll, to the team. Varzi was also brought on board, the only driver of the time seen to be comparable in skill to the great Nuvolari. It was Moll, however, who drew first blood; winning in Monaco after his teammate Chiron spun off towards the end of the race. Varzi followed up with a win in the Mille Miglia before leading his teammates home in the Tripoli Grand Prix in a clean sweep for the scuderia, as well as winning the Targa Florio after Chiron's success in the Moroccan Grand Prix.

The German teams of Mercedes Benz and Auto Union, however, were becoming increasingly difficult to beat, due to the massive support being put into the automotive industry in Germany under the instruction of Adolf Hitler. Moll managed a lucky win at the AVUS circuit in Berlin when the German cars retired with mechanical problems, but these were to be rectified by the time they arrived at the Nurburgring, where the beautifully streamlined silver cars came home first and second at the hands of Manfred von Brauchitsch and Hans Stuck (father of Hans Joachim Stuck). Hereafter the Italian cars were only able to succeed in the absence of the silver machines, either through retirement or non-appearance.

Tragedy was to strike the scuderia again at the Targa Abruzzo/Coppa Acerbo joint meeting when Moll, chasing Fagioli's Mercedes after the retirement of the other German cars, swerved off the road and hit a stone pillar and bridge, dying instantly. Years later Ferrari wrote about Moll: "never have I seen such coolness and self-assurance in the face of danger. Moll had what it takes to be one of the all time greats."

At Monza, Nuvolari was the highest placed of the Italian teams in fifth, and the destruction by the German cars was complete. Varzi signed with Auto Union for the following year and, with no one else to turn to, Ferrari re-signed Nuvolari, for a very large salary and 50% of all winnings, to the joy of the scuderia's workforce, if not the accountant. Rene Dreyfus joined him, and the designer Vittorio Jano returned to Alfa to come up with the replacement for his P3.

Ferrari, knowing that he would not be able to compete with the Germans for some time, started looking at other formulas which would offer him a chance at success. At the time the Formula Libre category offered the most likely chance, as there was no restriction in size or weight on the car. He commissioned his workers to take two P3 engines, placing them front and rear of a single seater chassis, and link them with a three-speed gearbox.

The resultant car was known as the Bimotore, and although it was badged as an Alfa Romeo it was in fact the first car manufactured entirely by Scuderia Ferrari, with the shield appearing as an enamel badge on the front of the car, rather than being painted on the side. The car was raced in Tunis, with Nuvolari at the wheel, but he was to return to the pits 3 laps later for new tyres, a process he repeated 12 times during the race. The same problem hit the car at the AVUS circuit and, after a publicity-seeking run near Firenze - where the record for fastest flying mile and kilometer was broken, the Bimotore was quietly retired.

Meanwhile the team recorded a one-two in Pau, followed up by yet another success in the Mille Miglia. The Grand Prix season, however, began as the previous one had finished, with the silver cars sweeping all others away. At the German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring, under the watchful eye of Hitler's Korpsfuhrer Adolf Huhnlein, the Germans were so confident of victory that they had only the German national anthem to hand for the post race celebrations. Nuvolari, in the same aging car as his teammates, who retired, moved slowly up from fourth to first before the pit stops, where he was stuck for over two minutes because of a pressure pump failure in the fuel rig.

Hereafter Nuvolari worked a miracle, using all of his abilities to run the car from sixth to second before the last lap where, pushing Brauchitsch to the full, the leader's tyre burst and Nuvolari was through for a win, in what was declared by many as the greatest drive ever. It was several minutes before an Italian flag was found to run up the pole at the ceremony afterwards, and the national anthem was provided by Nuvolari's own record, which he always carried with him for luck. The Germans were beaten on their home turf, and the Italians were delirious with joy, although it was to prove a brief high point in an otherwise disappointing season.

As part of this deal, engineer Gioacchino Colombo was transferred to the scuderia, and he immediately began plans to build a car with which to compete in voiturette racing - a single seater formula with engines restricted to 1.5 litres, and which the Germans did not compete in. The car was to be based on the Auto Union Grand Prix cars, including the rear engine, but Ferrari declined to follow through on the idea, stating that "it's always been the ox that pulls the cart." This conservatism was surprising, considering that he had spent a year having his cars soundly beaten by this very engineering design, but Ferrari always maintained the final say at his team, and the idea was shelved.

Ferrari won at the Mille Miglia for the fifth consecutive time, but the Grand Prix season ran much as the previous two. Another trip to New York had been a farce, with the Germans winning easily, and to make matters worse Nuvolari's 18 year old son Giorgio died of pericarditis while he was away.

Alfa had presented the team with a new car, the 12C, but it was a failure. Nuvolari, after much pressure, signed to drive with Auto Union, and morale at the scuderia was at an all time low. Alfa, reeling, announced that they were purchasing the scuderia outright, and that the team would be formed into a new factory team, Alfa Corse, with Ferrari running the team. The deal made Ferrari a wealthy man, but instead of being a padrone he was now merely an employee, albeit a well paid one.

The first race held under these new rules was the Tripoli Grand Prix, where 28 of the 30 entrants were in Italian cars, with Mercedes Benz entering the remaining two, driven by Herman Lang and Rudi Caracciola. The Germans finished one-two in that order, with Mimi Villoresi a distant third, leaving the Italian teams to mutter darkly about additives in the German fuel.

Within a month Mimi was dead, the result of an accident in testing, and shortly afterwards Ferrari was sacked by the Alfa chairman after a long running feud between Ferrari and chief designer Wilfredo Ricart. A section of the purchase document forbade Ferrari from forming another racing team using his name for a period of four years. His adventures in racing seemingly at an end, Ferrari retreated to Modena to lick his wounds while all around him Europe was bracing itself for war.

To be continued next week

Non mi piacciono i monumenti, he once said - monuments do nothing for me. Of course, the company he built has become the ultimate monument, in a country full of them, to him. Which is ironic, as he only started it in the first place to bankroll his love of motor racing. When asked which of the many cars his company had built he loved the most, he always replied his favourite was the next one that raced and won. The small, white haired old man was full of such quotes, and he seemed to delight in sharing them with the journalists, drivers, actors, sport stars and anyone else who made the pilgrimage to his factory, to his door, to spend some time with him (and, of course, to buy his wares). Such quotes added to the legend, and he had no problem with keeping the myth alive.

Enzo Anselmo Ferrari was born to Alfredo and Adalgisa Ferrari on 18 February 1898 during a snowstorm of such intensity that it took his father two days to get into Modena to register his birth, two years after his brother Alfredo (who was known as Dino) had entered the world. The boys shared a bedroom above their father's metal work shop, one of many in a region famous for such work, and they seemed to be very different in their outlook in life - while Dino was studious and performed well at school, the young Enzo preferred to run or ride his bike. It is said that at the time he wanted to be an opera singer, a sports writer or a racing driver - the latter presumably came from being taken, at the age of ten, to his first motor race. He briefly became a sports writer, at the age of 16 and before the war, for La Gazetta dello Sport, but the racing bug dug deep and stayed with him for his entire life.

Enzo Anselmo Ferrari was born to Alfredo and Adalgisa Ferrari on 18 February 1898 during a snowstorm of such intensity that it took his father two days to get into Modena to register his birth, two years after his brother Alfredo (who was known as Dino) had entered the world. The boys shared a bedroom above their father's metal work shop, one of many in a region famous for such work, and they seemed to be very different in their outlook in life - while Dino was studious and performed well at school, the young Enzo preferred to run or ride his bike. It is said that at the time he wanted to be an opera singer, a sports writer or a racing driver - the latter presumably came from being taken, at the age of ten, to his first motor race. He briefly became a sports writer, at the age of 16 and before the war, for La Gazetta dello Sport, but the racing bug dug deep and stayed with him for his entire life.

Ferrari would have to survive on the cars he already owned, or look elsewhere for the future. He made enquiries for alternative vehicles around Europe, but meanwhile business had to continue. Nuvolari won the Tunis Grand Prix before bringing the scuderia a win in the Mille Miglia. In Monaco he battled intensely with Varzi for 3 hours before his engine caught fire on the hundredth (and final) lap, at which time he tried to push it to the finish. A mechanic came over and attempted to help him and he was disqualified. His car broke down again in the Marne Grand Prix, and suddenly the cars were looking very old indeed.

Ferrari would have to survive on the cars he already owned, or look elsewhere for the future. He made enquiries for alternative vehicles around Europe, but meanwhile business had to continue. Nuvolari won the Tunis Grand Prix before bringing the scuderia a win in the Mille Miglia. In Monaco he battled intensely with Varzi for 3 hours before his engine caught fire on the hundredth (and final) lap, at which time he tried to push it to the finish. A mechanic came over and attempted to help him and he was disqualified. His car broke down again in the Marne Grand Prix, and suddenly the cars were looking very old indeed.

The following season was to prove equally disappointing, with Nuvolari joined by Giuseppe Farina in the lacklustre 8C-35. A one-two at the Mille Miglia didn't make up for what was a terrible Grand Prix season for the team, and the real highlight was an extremely fortunate win for Nuvolari at the Vanderbilt Cup, a competition designed to test the best of the American cars against those from Europe. This success led Mussolini, who was keen to see Italian cars compete well against those from Germany, to push Alfa into a deal to purchase 80% of the scuderia, providing much needed resources to the small team.

The following season was to prove equally disappointing, with Nuvolari joined by Giuseppe Farina in the lacklustre 8C-35. A one-two at the Mille Miglia didn't make up for what was a terrible Grand Prix season for the team, and the real highlight was an extremely fortunate win for Nuvolari at the Vanderbilt Cup, a competition designed to test the best of the American cars against those from Europe. This success led Mussolini, who was keen to see Italian cars compete well against those from Germany, to push Alfa into a deal to purchase 80% of the scuderia, providing much needed resources to the small team.

The 1938 season began with the unveiling of the new Alfa Tipo 158, which became known as the Alfetta, a beautiful car which won on debut at the Coppa Ciano in the hands of Mimi Villoresi after a fierce battle with the Maserati driven by his brother Gigi. In the Grand Prix circuit, however, the Germans still had the upper hand, which led to the Italian racing authorities announcing that henceforth all Grands Prix held in their territories would be run to the voiturette formula.

The 1938 season began with the unveiling of the new Alfa Tipo 158, which became known as the Alfetta, a beautiful car which won on debut at the Coppa Ciano in the hands of Mimi Villoresi after a fierce battle with the Maserati driven by his brother Gigi. In the Grand Prix circuit, however, the Germans still had the upper hand, which led to the Italian racing authorities announcing that henceforth all Grands Prix held in their territories would be run to the voiturette formula.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 6

Articles

The Cult of a Personality

A Driver's Dream

Back to the Future: The FIASCO War

Missing Senna

Columns

Bookworm Critique

On The Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |