Atlas F1 Technical Writer

The opening round of the 2004 season provided the ten teams with the new challenge of having to produce an engine that lasts for the entire weekend, as well as having to cope with regulation changes to the bodywork and the Grand Prix schedule. Atlas F1's technical writer Craig Scarborough reviews the cars on their racing debut, and looks at any mechanical changes introduced in Melbourne

Several far reaching rule changes affected engines, aerodynamics and the operation of the car over the weekend. However, the teams have reacted well and no one suffered the ten grid place penalty for an engine failure, although there has been a mix up in the teams' comparative pace. Whether this situation is due to a car's inherent design or a team's more cautious approach to the new rules remains to be seen as events unfold over the next few races.

One Engine Rule

Considering the immense challenge to get a highly strung F1 engine to last throughout an entire race weekend, the teams' reliability results by the of Sunday were impressive. The revised weekend format has assisted the teams - there was less overall running due to the change in the order of the sessions; and, admittedly, many teams opted for a safer strategy for the opening race, with well tested engines and cautious rev limits over Friday and Saturday. But overall, the rev limits of the cars were made public on the TV feeds and the near 19,000rpm limits of the top engines (BMW and Ferrari) were certainly impressive.

BAR's Jenson Button's incident on Saturday lead to a forced chassis change, in which the engine had to be transfer to the spare car. No teams posted a engine failure during the practice or qualifying sessions, and in the race itself there were few engine failures - with Kimi Raikonnen's being the most notable. For the next two flyaway races the pattern should be similar, albeit with the higher ambient temperatures iexpected in Malaysia and Bahrain affecting the teams a little more. But for the European season, starting at Imola, the first major steps in development should arrive.

Driver Aids

The Australian Grand Prix was the first recent race with a ban on launch control, and the start of the race proved less troublesome than might have been envisaged. All the cars left the grid cleanly and many made a similar paced start. Of course, the Renaults trounced the cars ahead - leading to speculation that an innovative form of legal launch control was used.

The rules dictate that no form of assistance can be used at the start, both in the form of traction control to limit wheel spin and manual control of throttle, and that clutch must be used. Previously the driver released a steering wheel button to initiate the launch sequence, which managed the throttle position and clutch release, reacting to wheelspin detected by the wheel sensors. Now the driver has to release the clutch paddle and modulate the throttle himself.

However, the way the clutch is released is under the control of the management system and while it cannot react to wheelspin, it can adopt a release pattern that best suits the track, tyres and temperature from information gathered from telemetry over the weekend. This way a passive launch control can be legally adopted.

Drivers now have to change the gears manually, albeit with the semi-automatic selection system operated from the paddles on the steering wheel. Onboard cameras showed the drivers were quite accurate in initiating the change at the correct revs. Over the course of a lap, individual gears require their own shift point, while lower gears generally use a shift at higher revs. So over the course of two laps, the shift point for the same gear in the same corner was within a hundredth of RPM.

Tyres

It was openly accepted that Michelin should have the upper hand in the opening races, with more top line teams and an ambitious development program. Bridgestone meanwhile were only supplying one top team plus a few mid-field teams, they had a relatively poorer season in 2003 and were low key in winter testing.

In the later tests, the Bridgestone shod Ferraris turned in a more competitive pace, and it now transpires that Bridgestone's two development teams had taken independent directions on construction and compound. These were then combined into the final run of tyres for the last tests and subsequently Melbourne. The result was a tyre with some Michelin-like properties - that is, a drop of in performance over the opening two laps before bedding in and remaining durable over long runs.

Michelin meanwhile took tyres that suffered graining in the cooler conditions and tight turns. Teams running too little downforce or scrubbing tyres in slow corners were losing even more grip from the car. McLaren, for example, had pre-season problems with getting heat into the front tyres, and this was exacerbated by the Melbourne track. Subsequently, they suffered heavily in these conditions. Renault conversely chose a tyre to match the cool weather and found their well balanced chassis looking after the tyres perfectly.

A specific tyre performance at this track should not be considered definitive for the season, however, as Albert Park track is fairly unique. The weather was relatively cool, the track surface dusty, un-rubbered and it consists of tight turns. Forthcoming races will be in hot, humid conditions, on a purpose-built track surface with fast straights. These are traditionally Michelin territories.

Downforce and Changes since Launch

With the regulation changes made to the rear wings for this season, most of the teams raced bodywork seen frequently in winter testing. Only a few new solutions were debuted in Australia, which is surprising as the street circuit layout favours higher downforce. It is possible that some teams chose not to run solutions still in development, preferring the safer route for the opening race.

Of all the new parts on show only BAR and Toyota's rear wing endplates were truly new solutions. Remakes on old solutions were seen with Ferrari running their mid wing and BAR running a low mounted shelf-wing. Progress on the rear wings themselves were seen with 3d shaping appearing on most cars, which sacrificed downforce for less drag, suggesting the 5% loss in downforce has been more than recovered and the FIA regulations change has not had a lasting impact.

Team by Team

Ferrari

Arriving at Australia as the underdog against the Michelin shod teams, Ferrari rolled out a car in a format seen at the last test at Imola. Most obvious among the updates to the car was the mid wing mounted behind the rollover bar. This sits in a blind spot in the bodywork regulations, pinpointing its position and width to one that is perhaps less than ideal.

While this is a wing due to its aerofoil shape, its function is not to produce its own downforce, but to act as a turning vane for the air flowing over the car and to the rear wing. The flat angle of the wing directs and conditions the flow to improve the function of the rear wing.

A new front wing with a flat mid span and flicked up outer sections, was matched to endplates with split Toyota-like dive-planes. This fed back to new two panel bargeboards, with the stepped outer panels reaching right under the front suspension.

Williams

After pre-season testing, Williams were clear favourites for the 2004 title, yet they didn't shine in Australia as one might have expected. As the first team to debut their car back in January and a string of fast trouble-free laps around the European test circuits, the car arrived in Melbourne barely altered from its launch spec. Still, they were the fastest pair of Michelin shod cars, with only their getaway from the grid dropping them behind their rivals.

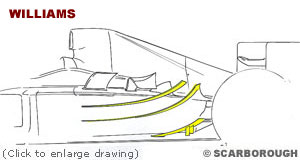

This creates lower pressure ahead the rear wheels and judging by the height of the rear of the flip-up, it also splits the flow over and under the rear wishbone. Williams also sported a new rear wing with less cambered chords nearest the endplate in a similar 3D format to that seen last year.

Renault

Renault is very much an unqualified threat, after winter testing proved the car to be fast over longer runs. The Renault team with their technical management depleted and replaced over the winter impressed with their pace and new engine. No one yet is sure of the power output of the 72-degree engine - it produces more power than the late spec, wide angle 2003 engine, yet that could still put the team some 50hp down on the leading manufacturers. Most likely the gap is less and more constrained by the revs the engine was able to reach, being some 1000rpm down on the other teams.

Yet the drivers were able press on throughout the race at top revs with reliability. More than matching the engine is the chassis, with its tight sidepod shape exposing its apertures. Renault ran at the relatively cool Melbourne race with three grills added to the sidepods, one inboard of the chimney and two behind it, the lower outlets remained covered up. Renault's more efficient use of the Michelin tyres allowed their drivers to keep up their pace in the race without the degradation seen on their similarly shod rivals.

BAR

Even less predictable than Renault's pace, was that of BAR. After posting seriously quick and repetitive times in testing, BAR were expected to pressure the leading teams. And, while BAR didn't top the timesheets throughout the weekend, they were very close to Williams's times and beat Renault and McLaren in many sessions. A combination of the new Honda engine and the evolved BAR chassis represents a major leap for the team.

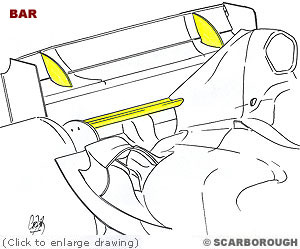

Appearing Melbourne with the much tested shelf wing and much hidden rear wing fences, BAR have evolved from their launch specification.

The other solution to improve rear downforce efficiency are the two fences added to the rear wing. These act like intermediate endplates to reduce the higher pressure created in the middle section of the wing, spilling into the lower chord and lower pressure outer edges of the wing. By containing the pressure differentials, the vortex produced at the main endplate is kept smaller, at the expense of a smaller vortex created by the fence.

Since their launch, the large hot air outlets on the car's sidepods have been dropped for cooler conditions or shorter runs. These result in a clean sidepod shape under the winglet.

This was BAR's first race with Michelin tyres and Alcon brakes. The tyres were more worn at the rear than desired towards the end of the stints and the brakes were looking marginal towards the end of the race. But overall the performance was convincing enough to put BAR at the head of the midfield.

McLaren

There was initial optimism in testing with the MP4-19, but the later engine upgrade and tyre developments left McLaren trailing in the latter half of the pre-season testing. Undisclosed issues with the engine's installation (probably down to heat or vibration), gearbox problems and front grip blighted the car's potential.

The car run in Melbourne can only be considered an interim spec, as its engine was detuned to encourage reliability, the carbon fibre cased gearbox was replaced with an alloy cased version and the new curved front wing was not evident over the old "W" format wing.

Sauber

Sauber did not appear to run with many significant developments since early testing introduced the definitive floor for the car. As the top mid-field team on Bridgestone tyres they seem to suffer behind the hoards of Michelin-shod cars. From the TV footage showing RPM limits, the Ferrari provided Sauber engine revved as well as Ferrari's own engines, to the top end of 18,750rpm.

Jaguar

After moderate success in testing, the Jaguar team appeared at Melbourne with the usual front wing/rear wing updates and little other noticeable change.

Toyota

After a good showing in 2003 and an evolution in their car design, the Toyota did not show the pace expected in winter testing or in Melbourne. Now with a definitive front wing following the established flat centre span and flicked up outer spans, the car looks the part. On top of that, the powerful engine and the Michelin tyres are no hindrance. Therefore, the chassis/aerodynamics are clearly the weak link in the package.

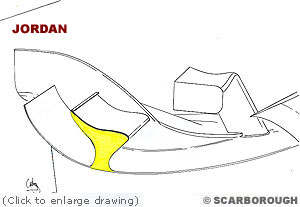

Jordan

After a brief test in the UK before setting off to Australia, Jordan focussed more on testing their drivers than new parts. One novelty was a change to the sidepod flip up after several seasons with their old set up. The minor change downsized the old larger endplate to a smaller version with a small support to the lower parts of the bodywork.

Minardi

Only officially launched at Melbourne, the Minardi did not have any technical novelties other than those seen in their initial testing.

After a winter of testing new solutions to meet the demands of the regulation changes for 2004, the buck stopped in Melbourne.

Although seen in the later winter tests, the Williams flip-up arrangement ahead of the rear wheels was effectively new for Melbourne. Williams have run a single large flip-up and in the latter races of 2003 added a smaller upper flip-up above the larger one. This twin set up was augmented with the new development of a lower, almost floor level flip-up. This matches the curves of the upper ones and sits just a few centimetres above the floor, mounted to the sidepod at its front end and supported by two stays at its rear end.

Although seen in the later winter tests, the Williams flip-up arrangement ahead of the rear wheels was effectively new for Melbourne. Williams have run a single large flip-up and in the latter races of 2003 added a smaller upper flip-up above the larger one. This twin set up was augmented with the new development of a lower, almost floor level flip-up. This matches the curves of the upper ones and sits just a few centimetres above the floor, mounted to the sidepod at its front end and supported by two stays at its rear end.

The shelf wing is an aerofoil mounted between the flip ups and connected to the engine cover. Much as Ferrari use their mid wing as a turning vane for the airflow, BAR's shelf wing acts in a similar way. The wing profile is cambered to almost horizontal so it doesn't create a large load in itself, but shapes the flow under the rear wing to reduce separation.

The shelf wing is an aerofoil mounted between the flip ups and connected to the engine cover. Much as Ferrari use their mid wing as a turning vane for the airflow, BAR's shelf wing acts in a similar way. The wing profile is cambered to almost horizontal so it doesn't create a large load in itself, but shapes the flow under the rear wing to reduce separation.

New features on the car were longer exhausts, which were protruding through the fairing by several centimetres, and the redirected flow from the pipes was scorching the bodywork along the rear of the car. bargeboards were also revised with a small third panel included between the main and keel boards.

New features on the car were longer exhausts, which were protruding through the fairing by several centimetres, and the redirected flow from the pipes was scorching the bodywork along the rear of the car. bargeboards were also revised with a small third panel included between the main and keel boards.

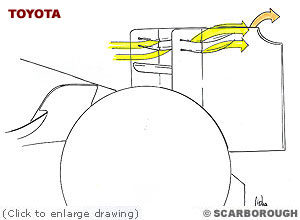

One innovative detail on the car was the rear wing endplate. As with Renault, Toyota have sought a way to equalise the pressure between the high pressure above the flap and lower pressure to the side of the endplate, to prevent a strong drag-inducing vortex being created at the tip of the wing. To achieve this there are two slits in the endplates ahead of the rear flap that pass high pressure flow from within the endplate to outside, directing towards the wing tip. The local high pressure region tricks the flow inside the endplate into forming a smaller vortex.

One innovative detail on the car was the rear wing endplate. As with Renault, Toyota have sought a way to equalise the pressure between the high pressure above the flap and lower pressure to the side of the endplate, to prevent a strong drag-inducing vortex being created at the tip of the wing. To achieve this there are two slits in the endplates ahead of the rear flap that pass high pressure flow from within the endplate to outside, directing towards the wing tip. The local high pressure region tricks the flow inside the endplate into forming a smaller vortex.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.