Atlas F1 Columnist

With recent events suggesting Formula One might see another power struggle between the governing body and the sport's participants, it is perhaps worthy having a look at what happened the last time around, and how miniscule today's battles are compared to that Great Big War. In a series of articles, Atlas F1's Don Capps recounts the war that became known since as The FIASCO War, and how it completely changed the face of F1. This week, the final instalment: Götterdämmerung, the Twilight of the Grand Prix Gods...

Here, briefly, is what came out of the FISA Plenary Conference on that fateful October day in Paris. First, the Plenary Conference approved the actions taken by the FISA Executive Committee in January. The banning of the sliding skirts used by the ground effects cars had been the point over which the FOCA and the FISA had crossed swords in the first place. Now, the ban was upheld, effective from the start of the 1981 season.

Second, as of the 1981 season, there would be a new "FIA (Federation Internationale de l'Automobile) Formula 1 World Championship," which would be the exclusive property of the FIA. There would be championships for drivers and constructors, just as in the past. However, the participants had to be licensed by the FIA (for drivers, the FISA established a new "Super License" for this purpose), and the events had to have contractual agreements requiring all parities involved - the FISA, the respective ASN (Autorité Sportive Nationale), the competitors, the organizers, and the circuit - to abide by the regulations governing the FIA Formula 1 World Championship.

In addition, the usual supplementary regulations issued by the respective organizers would now be replaced by a standard set of regulations which would be used by all those hosting a championship event. They would be in both French and English. The championship would consist of no more than 16 rounds nor less than eight rounds. The minimum number of starters would be 24, or should the number of entries exceed 30, then 26 would be the number of starters. If necessary, the organizers could admit cars conforming to the Formula 2 regulations to participate.

The maximum distance of 320 kilometers or two hours carried over from the previous championship. The scoring system was based on splitting the season into two equal parts, with drivers being able to count their results from "half plus one" of the races from each part of the season. The scoring system - 9,6,4,3,2,1 - remained the same.

Teams and organizers wishing to participate in the 1981 championship had to indicate their intention to do so during the period between 1 and 15 November. The FISA would announce those participating a week later, on 22 November. Teams participating had to sign contracts binding them to adhere to all the relevant FISA contracts and regulations. This included the new FISA Standard Financial Regulations. Failure of a team to participate in all of the qualifying rounds of the championship would result in a fine of $20,000 per car per event. Entrants not scoring points in the 1980 constructors' championship had to provide the FISA with information about their organizations and post a $30,000 bond with the FISA which could be refunded at the end of the season if their participations was satisfactory. Should a team not anticipate participating in a complete season, it must provide the FISA with three months' notice and the posting of the $30,000 bond. Should a team wish to run an additional car in certain events, a month's notice was necessary, and no points could be scored by the "extra" car.

And, should there be any thoughts of a "pirate" Formula One series, the FISA made it clear that any such endeavor would be met with harsh penalties. The Plenary Conference supported the FISA in its reiteration of the penalties that were already "on the books," as well as ensuring that a clear message was sent to the FOCA teams that the FISA most certainly meant business. The withdrawal of licenses of not only the teams, organizers, and drivers involved, but even those of the ASN who allowed such events to occur within their jurisdictions.

Needless to say, the FOCA proposal offered to the FISA Plenary Conference was rejected. The retention of sliding skirts was never given any serious consideration by the Plenary Conference. The FISA had offered the constructors, and not just the FOCA, the opportunity to present a set of proposals formulated by a committee composed of Colin Chapman (Lotus), Gordon Murray (Brabham), Patrick Head (Williams), and Teddy Mayer (McLaren). These proposals were obviously "Cosworth-centric." The group wanted an immediate adoption of a "fuel flow" formula, a maximum fuel capacity of 210 litres, and the phasing out of the sliding skirts. The proposals had to be unanimously approved by the constructors. With Ferrari and Renault dissenting with the proposals, so much for the FOCA.

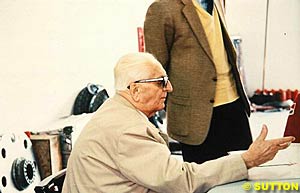

It was also revealed that Enzo Ferrari had offered his services to Bernie Ecclestone of the FOCA as a mediator for the problems which seemed to exist between the FISA and the FOCA. Ferrari wrote that he would work to ensure that Ferrari, Renault and Alfa Romeo would support the continuity of the existing FOCA contracts. However, the on-going lawsuits brought by the FOCA would have to be dropped as a pre-condition. This meant the acceptance of the FISA as the sole source of sporting and technical power in Formula One, to include accepting the existing and future regulations applicable to Formula One.

Ferrari proposed to broker a "protocol" for those participating in the forthcoming FIA Formula 1 World Championship. Ferrari offered a period of three years during which the FOCA would continue to manage the financial arrangements of F1 events. During this period, the FOCA would develop a standard contract for use by all the organizers. There would be an indexing system based upon geographical region to account for any rises in costs due to inflation. Ferrari also suggested that all funds be disbursed immediately at the conclusion of each event.

In the days immediately following the release of the Plenary Conference actions, the silence from the FOCA was deafening. However, on 15 October, a week following the Plenary Conference, the FOCA participated in a meeting of the F1 sponsors in Milano. The sponsors were concerned about the events of the past months since, after all, it was their money being bantered around. What got the attention was that in addition to the new schedule for the 1981 FIA F1 World Championship, also revealed were the dates for a 15-round FOCA championship! There was some overlap, both calendars listing events at Kyalami, Rio de Janeiro, Jarama (on different dates!), Dijon, Silverstone, Hockenheim, Zeltweg, and Zandvoort. The 1981 FISA and FOCA calendars looked like this:

The sponsors looked at this with more than a little dread. While those present went on record as stating that the best solution was a single championship series, there were factions within this group. Gitanes, Elf, and Essex expressed their preference for FISA, while Leyland, Candy, and Parmalat sided with the FOCA side. John Hogan of Marlboro said that Philip Morris was officially neutral. He also said that he wanted the two sides to find a reasonable compromise. Some of the sponsors not present voiced their displeasure with the way things were going, offering the opinion that some would consider their options for the coming year very closely.

The presence of this FOCA calendar was viewed by many as a mere canard and designed simply to serve as a bargaining chip for the almost certain upcoming negotiations. Thus far, the FOCA had not announced a "pirate" or "breakaway" series to compete head to head with the FISA F1 World Championship. That had many wondering exactly what was really going on. The FISA immediately made it known that the appropriate ASNs of South Africa, The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Spain, and France had issued denials of any such a FOCA series being on their calendars. All were quick to make their allegiance to the FISA (and Jean-Marie Balestre) very clear.

However, the FOCA finally broke its silence. It pointed out that none of the ASNs mentioned by the FISA actually owned a circuit. It also said that it would soon reveal that there were contracts in place for the events listed on the calendar it had revealed at the Milano conference with the sponsors. It said the events would be held with or without the blessing of the FISA.

There were rumors that Enzo Ferrari and Bernie Ecclestone had met in Modena to discuss the current situation. Ecclestone was said to have asked Ferrari to participate in the FOCA series, but Ferrari vowed that he had pledged his allegiance to the FISA and thank you very much, but no thank you. It was also said that a revised FOCA calendar would be released in the next week or so.

Then it happened. On 31 October, the FOCA ratcheted up the war more than a few notches: The World Federation of Motor Sport (WFMS) would sanction the World Professional Drivers Championship (WPDC) beginning with the 1981 season.

The calendar for the WFMS series differed in detail from that shown two weeks earlier:

Just a cursory glance at the calendars showed that there was going to be a serious problem in 1981 if the FISA and the WFMS both went ahead with their plans. And there was now what more than a few had been trying to avoid - an open breach between the FOCA and the FISA. Plus, both sides expected its allies to align themselves accordingly.

The WFMS was the previous FOCA proposals codified. The WFMS technical regulations for its "Formula 1" retained the sliding skirts needed for ground effects, but reduced the plane area to four square meters, a reduction of about a third from that of the 1980 cars. There would be a "fuel-flow" formula of 50 cubic centimeters per second. Tires would be restricted to rim sizes between 13 and 15 inches with a volume of 400 litres and a threaded design would be introduced. There would be a ban on refueling during a race. The minimum weight would be 575 kilograms. By the beginning of the 1982 season, a driver survival cell requirement would be implemented. There would be a three year stability period for any regulations. The WFMS would retain the same points systems as the FISA championship, but all scores would count, none being dropped. Race would be between 304 and 320 kilometers or two hours.

Ironically, at the same time the WFMS was making headlines and the troops turning skirmishes into battles, the replacement of the "FOCA Package" with the "FISA Package" as the deals being offered to the organizers were termed, Enzo Ferrari had gotten Balestre and the FISA to rethink their position, despite how the Plenary Conference had voted in October. Ferrari suggested that "FOCA Package" continue to be offered but with a small twist, that being that the teams would be given their shares individually by the organizers after each event rather than through the FOCA.

Balestre considered what Ferrari said, and after mulling things over, thought that the Ferrari proposal made sense. That the two "packages" were almost identical in most aspects meant that, to a large extent, the organizers would not really notice much difference. The breakdown of how the money was to be "earned" was almost the same in each package, with FISA's breakdown being starting money 35%, practice performance 20%, and race results 45%. And besides, this proposal would remove the FISA Standard Financial Agreement from the table as an issue. That is, if there wasn't a World Professional Drivers Championship being sanctioned by the WFMS.

In its declaration of war on the FISA, the FOCA said it created the WFMS because of two issues: the changing of technical specifications without sufficient notice of two years; and the interference of the FISA in the commercial affairs of Formula One. The purpose of the FISA, stated the FOCA, was to be the rules maker (only after consulting with the participants in the opinion of the FOCA) and the referee - in other words, the body responsible for the sporting aspects of racing. The FOCA also said that currently the officials of the FISA contributed nothing to the actual running of a Grand Prix event. They tended to be "armbands" and show their faces only at events such as Monte Carlo where they appeared in droves, compared to virtually none at other less glamorous venues.

The FOCA also made it clear that they had run the financial and commercial side of Grand Prix racing in a manner which was demonstrably fair and beneficial to not only its membership but the sport. It had negotiated travel arrangements which benefited its members. It had made it possible for several events to exist due to the FOCA handling the running of those events. This latter was something that the FISA completely failed to not only comprehend, but was incapable of doing. The rhetorical question was: Who does the most for Grand Prix racing? The FOCA or the FISA?

Not being satisfied with merely thumbing its nose at the FISA and Balestre, the FOCA said that the FISA lacked the authority to deny the WFMS from running its WPDC. The FISA was merely a collection of private clubs which had given itself the authority to run motor sport, there being nothing to prevent other organizations from doing the same thing. Indeed, by blacklisting those holding WFMS events, the FISA simply reduced the number of venues available to its own championship series.

The FOCA also warned that the FISA and its clear preference for the manufacturers' F1 teams over the professional F1 teams would lead to a decline in the state of the sport. The manufacturers' teams had no true stake in Grand Prix racing and could - and would - depart at any point that they wished. Should the professional Grand Prix teams be allowed to be pushed out of the sport, what would happen, the FOCA asked, when the manufacturers dumped the sport once they had milked it for whatever publicity value they could?

When the window opened for entries for the 1981 FIA Formula 1 World Championship, there were three constructors which quickly filed their intentions to contest the championship: Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, and Renault. All entered three car teams. Another team considering entering the FISA-run championship was the Osella team. Some reports stated that the Talbot Ligier-Matra team would opt for the FISA series as well. The FISA was also quick to point out that the FOCA calendar contained events which the host ASNs stated would not accept entries from the FOCA teams running in the "pirate" series.

The FOCA - the WFMS - responded by stating that it had contracts in place with the very same organizers that "shared" events on both the WFMS and FISA calendars. The WFMS intended to see these contracts honored and should there be attempts to not honor the contracts already in place, then the WFMS would take the appropriate measures. This meant, the FOCA were quick to point out, that the FISA calendar would have perhaps only six events for only eight to 10 cars per race.

Into this slugfest was introduced a statement from the Grand Prix Drivers Association (GPDA) which said that it had requested early in the 1980 season that steps needed to be taken to reduce the cornering speeds of the current Grand Prix cars. The steps taken by the FISA - banning the sliding skirts in particular - were in line with what the GPDA deemed the correct direction to be taken.

The FISA launched a counter-attack on the WFMS/FOCA in mid-November. Contrary to what had been said earlier, it now claimed that it had at least 15 cars from six teams and 13 circuits for its championship. And the FOCA were clearly mistaken about many of the venues on its calendar since Spa-Francorchamps denied any intention to host a FOCA event, nor was there to be an event in the New York City area as the FOCA claimed. Many of those the FOCA listed as being aligned with their series were vigorously denying any involvement with the WFMS or the FOCA, according to the FISA. The FOCA stated that it intended to run an event at Imola, but Imola would be hosting a second Italian event in 1981, the FISA pointed out.

The FOCA suddenly found itself in a bit of a pickle when the Royal Automobile Club (RAC) Motor Sports Association (MSA), the organizers of the British Grand Prix, announced that the event would be part of the FIA Formula 1 World Championship. That the WFMS had thought this event to be solidly in its camp - with the contracts to prove it - and then to suddenly have the RAC seemingly switching sides made a messy situation even more nasty. The FOCA turned on the RAC MSA with a vengeance. The RAC MSA stated that it had to consider the thousands of international competition licenses which would become null and void if it aligned itself with the WFMA and its WPDC. The FOCA loudly threatened legal action. The RAC countered that the FISA needed to reform itself from within and that although the WFMS had many good ideas, the fact remained that it had to do what it had to do.

Sensing that its support was clearly slipping if its best ally in the first battles of the war, the RAC MSA, was now aligning itself with the FISA elements, the FOCA decided to tender a new compromise proposal to the FISA. The FOCA proposed a new Formula 1 Commission composed of voting and non-voting members, that decisions be made by requiring a 70% vote to approve changes to the committee; that technical changes - the ban on sliding skirts - be delayed until the first European event, the smaller tire proposed by the FOCA be adopted immediately, that there be new set of standards for chassis construction, there be a two-year stability rule for technical changes, and that all the legal cases, name calling, and other such "unsporting" behavior cease immediately.

The FISA rejected the FOCA compromise outright. Many were even unaware that there had been a compromise proffered until many days later when they read about it in the motor sports weeklies. To some it seemed that Balestre was not interested in compromise and to others that he was taking a firm line to keep things in order. Whatever one believed, it was clear that Grand Prix racing was dying a shameful death, being almost overlooked in the bickering and exchange of insults which were now commonplace and marred the once happy world of a sport.

Here and there a few brave voices tried to get the warring factions to begin speaking with each other and not "to" the other and, most importantly, to take the time to listen to the other. Unless the warring parties soon found a common ground to begin negotiations from, there would be no Grand Prix racing to save, it having been crushed by the two mighty armies wrestling in the mud and the muck. Sponsors were already informing both parties that unless there were a cessation to the hostilities they would walk out and find other sports into which they would pump their monies.

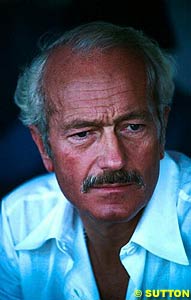

The FISA "Formula 1 Round Table" in Paris was a strange affair. The FISA held its event while just literally meters away the FOCA, nee WFMS, held a press conference to discuss the same issue. When informed that their compromise had been summarily dismissed, the opinion among the FOCA members present - Max Mosley, Bernie Ecclestone, Colin Chapman, Jackie Oliver, Frank Williams, Teddy Mayer, Emerson Fittipaldi, Ken Tyrrell, Mo Nunn, Peter Warr, John Woodington, and Gunther Schmid among them - was mixed, ranging from fierce anger to grim acceptance of a bad situation now made seemingly worse.

The concept of unconditional surrender was one that Balestre now seemed to embrace all the more firmly now that he sensed that the FOCA teams were beginning to be worn down by the constant pounding from the FISA and its allies. Talbot Ligier had now defected to the FISA camp. More of the organizers were lining up behind their ASNs and the FISA. Goodyear was now sending a clear signal that it was considering a withdrawal from Grand Prix racing. Many were now beginning to see that the FIASCO War might be ended when there were no sponsors or teams left to run either series.

The FISA announced that the 1981 Argentine Grand Prix might be postponed given the current climate within the sport. The same might be done with the South African Grand Prix at Kyalami. Both organizers said that was news to them.

Meanwhile, the FISA was making efforts to sow dissent among the FOCA as the start of the season drew closer and closer. It suggested that it would be willing to extend the date for filing an entry in the new FISA championship for any FOCA team willing to avail itself of the opportunity to compete in the championship next season. A spokesman for the FOCA said that if Balestre wanted to talk, he could talk to the FOCA leadership….

As the end of 1980 approached, despite the rosy prospects for eventual victory being offered from both warring camps, many of those whose presence in the grandstands or in front of television screens or whose purchase of the products of those sponsoring Grand Prix cars made it all possible began to express their discontent in many and varied ways. The purchase of tickets for many of the 1981 season's events were lagging far behind the usual pace.

Then Goodyear proved that the rumors weren't rumors after all. On 4 December it announced that it was pulling out of Grand Prix - as well as all of the other European racing series it supported - racing effective immediately. Goodyear stated that the current conditions in Grand Prix racing were one of the factors in its decision to quit. This got the attention of many within the Grand Prix community like few of the other earlier events never had.

Then the FISA announced that it was postponing the Argentine and South African races. This placed the Argentine race in doubt and the organizers of the South African Grand Prix expressed open reluctance to do so. The FOCA pounced on the FISA announcement with an "I told you so" style rebuttal. The Buenos Aires track was also being denied a permit until safety work had been carried out. In any case, the Argentine Grand Prix was not to be held on its assigned January date.

As 1980 ended, Balestre expressed confidence that the FISA would prevail and made it clear that he was in no mood to back down on anything. He said that he had given the FOCA teams plenty of time to build cars which conformed to the new "skirtless" regulations. He also announced that there would be a new system for counting scores in 1981, one half of the number of the season's races plus two.

The FOCA teams geared up for a legal campaign against the FISA. The FOCA lawyers were requesting a series of injunctions be issued in order to prevent a number of the race organizers from honoring their contractual obligations with the FISA.

However, it seemed somehow that the spark was fading in both the FISA and the FOCA camps. There was no doubt that the war had inflicted heavy damage on both of the warring powers. In the dull Winter days of early 1981, as more and more involved openly expressed the idea that the war must end, and end soon, what little hope that there had been for a peaceful solution just weeks earlier seemed as remote as ever. A December meeting between Balestre and Ecclestone was deemed by Ecclestone as a "waste of time."

Then as the start of the season approached in South Africa, it was announced that the event would be a FOCA-only affair. It was also confirmed that the Long Beach Grand Prix was discussing the possibility of switching to CART in the near future. There was now a series of discussions being conducted by intermediaries to find an end to the FIASCO War. Despite the promise the new talks offered, no one was taking anything for granted. In the center of the talks was Enzo Ferrari.

The running of the South African Grand Prix and the approach of the Long Beach Grand Prix stirred the wheels of compromise to spin faster. Balestre was now faced with the prospect of several of his teams - notably Renault - being forced to break ranks since they needed to race in the important American market.

Finally reason prevailed. Balestre now found good reason to compromise, and the FOCA teams realized that they could live with a deal brokered to protect its commercial interests, even if it meant ditching the sliding skirts. In the end, the FISA got rid of the sliding skirts and the FOCA keep control of the commercial interests in an arrangement known as the Concorde Agreement. Despite all the former talk about open covenants openly arrived at, Balestre agreed to the stipulation that details of the Concorde Agreement be kept secret and known only to those directly involved. The agreement was culminated in early March and while there should have been much celebrating, there was actually not at all the level and intensity one would expect. There had been too many harsh words and too many rock and nail-studded cow pies tossed to get all concerned to forgive and forget.

The Long Beach Grand Prix was run with an almost spooky calm. Riccardo Patrese put his Arrows on the pole and Alan Jones and Carlos Reutemann finished one-two for Williams. The first "FISA" team to finish was Alfa Romeo with Mario Andretti taking the fourth spot in the results. The only fly in the ointment was the stewards rejecting the Lotus 88, the clever "twin-chassis" design of Colin Chapman.

The Brazilian Grand Prix saw the just as clever Gordon Murray find a loophole to beat the new six centimeter clearance rule by using hydro-pneumatic suspension. However, that, as they say, is another story….

So, when it is all laid out and looked at, just what did the FIASCO War really accomplish? For starters, it was literally the end of "Grand Prix" racing since the new championship was explicitly a "Formula 1 World Championship." It also saw that although there was a compromise in which it was at first thought that Balestre walked away with the better end of the lollipop, in the long run, the FOCA retention of the commercial rights would see who really got the best end of the deal. Indeed, a decade later would see Max Mosley becoming president of the FIA, something thought beyond reckoning in the days following the FIASCO War.

Perhaps, though, its greatest legacy was to show how the need to compromise was necessary if the sport - now morphing into a true business - was to keep the all important bottom line in the black. The harm done by the FIASCO War on the commercial end of the sport, sponsor support, took time to undo and not much more time to push to levels previously unimagined. The F1 events now operated to a standard set of rules as far as practice times, race starts, support facilities, and used a uniform scoring and timing system.

Although many seem to not realize where the roots of the slick, well-polished show of today sprang from, it has not come without a price. In place of the local flavor and unique environment of each race during the Grand Prix era, there was soon a uniformity which blurred the differences of each F1 event from the others only in small details. While today there are differences, they are not truly "different" in those differences. Gone are the virtually open paddocks and access to the operations of the teams being visible to all.

Many of the harsh and extremely nasty aspects of the FIASCO War I decided to avoid for a simple reason: it was present on both sides of the dispute in abundance, and did neither side any credit. It also tended to obscure the issues at hand and substituted blind emotion and visceral comments for commentary. That Grand Prix racing was in need of change cannot be disputed. The sliding skirts were a technical box canyon and an inelegant solution to a problem. That safety needed to be vastly improved is also without question a factor when looking at this era. That these important issues often were lost in the fury of the battles is a good reason to read my words and hope that we never experience such days ever again.

The FIASCO War was indeed the Götterdämmerung, the Twilight of the Grand Prix Gods...

The year-long struggle between the Federation Internationale de Sport Automobile (FISA) and the Formula One Constructors Association (FOCA) reached a demarcation point on 8 October 1980. On that day, the FISA Plenary Conference met in Paris. A war which had become a quiet exchange of barbs to the unwary on either side now found itself sliding into the very thing that most had been working to avoid: a war with unconditional surrender.

The Plenary Conference approved these new FISA Standard Financial Regulations. On top of the information already discussed, these regulations stated very clearly that the only way to run in the FIA Formula 1 World Championship was to sign a contract with the FISA, which delineated the financial arrangements governing that participation. The FISA would retain a small percentage of the monies exchanging hands each race for its operating expenses. There would be a built-in index during the five years over which the new contracts would be in place to prevent steep jumps which FISA accused the FOCA of imposing from one year to the next. The figures in the new contracts would be made public knowledge, ending the secrecy that the FISA accused the FOCA of maintaining in its contracts.

The Plenary Conference approved these new FISA Standard Financial Regulations. On top of the information already discussed, these regulations stated very clearly that the only way to run in the FIA Formula 1 World Championship was to sign a contract with the FISA, which delineated the financial arrangements governing that participation. The FISA would retain a small percentage of the monies exchanging hands each race for its operating expenses. There would be a built-in index during the five years over which the new contracts would be in place to prevent steep jumps which FISA accused the FOCA of imposing from one year to the next. The figures in the new contracts would be made public knowledge, ending the secrecy that the FISA accused the FOCA of maintaining in its contracts.

Date FISA FOCA

25 January Buenos Aires

7 February Kyalami Kyalami

15 March Long Beach Long Beach

29 March Rio de Janeiro Rio de Janeiro

3 May Montreal

9 May New York

17 May Zolder

31 May Monte Carlo

7 June Jarama

21 June Jarama Spa-Francorchamps

5 July Dijon Dijon

18 July Silverstone Silverstone (or Brands Hatch)

2 August Hockenheim Hockenheim

16 August Zeltweg Zeltweg

30 August Zandvoort Zandvoort

13 September Monza Imola

27 September Montreal Mexico City

4 October Watkins Glen

?? October Las Vegas

Date WFMS FOCA

25 January Buenos Aires

7 February Kyalami Kyalami

15 March Long Beach Long Beach

29 March Rio de Janeiro Rio de Janeiro

2 May New York

17 May Imola Zolder

31 May Monte Carlo Monte Carlo

7 June Jarama

21 June Spa-Francorchamps Jarama

5 July Dijon or Anderstorp Dijon

12 July Anderstorp

18 July Silverstone Silverstone

2 August Hockenheim Hockenheim

16 August Zeltweg Zeltweg

23 August Zandvoort

30 August Zandvoort

13 September Montreal Monza

27 September Watkins Glen Montreal

4 October Watkins Glen

11 October Mexico City

18 October Las Vegas

The FOCA squarely placed the blame for the split on the FISA and Balestre. They accused Balestre of only meeting with the FOCA representatives at his convenience and that despite much effort and negotiations conducted in good faith on their part, that Balestre failed to do so on his part. Since neither Balestre nor other FISA officials had the level of investment in the sport as the members of the FOCA did, there was a failure on the part of Balestre and the FISA to fully comprehend the problems created by arbitrary, short-notice changes to the technical regulations.

The FOCA squarely placed the blame for the split on the FISA and Balestre. They accused Balestre of only meeting with the FOCA representatives at his convenience and that despite much effort and negotiations conducted in good faith on their part, that Balestre failed to do so on his part. Since neither Balestre nor other FISA officials had the level of investment in the sport as the members of the FOCA did, there was a failure on the part of Balestre and the FISA to fully comprehend the problems created by arbitrary, short-notice changes to the technical regulations.

Mario Andretti said it was "an ego thing. Balestre can't handle the job any more." This was one of the more polite things being said. And Andretti was going to drive for a FISA team in 1981, which did not prevent him from calling it like he saw it. Comments from Alan Jones on the matter were so riddled with the Great Australian Adjective that they were often rendered into something along the lines of "Jones was critical of Balestre during the interview."

Mario Andretti said it was "an ego thing. Balestre can't handle the job any more." This was one of the more polite things being said. And Andretti was going to drive for a FISA team in 1981, which did not prevent him from calling it like he saw it. Comments from Alan Jones on the matter were so riddled with the Great Australian Adjective that they were often rendered into something along the lines of "Jones was critical of Balestre during the interview."

After barely a month's existence, the FOCA pulled the plug on its WFMS. One reason was that it was suggested that the contracts that FOCA had in place did not mention the WFMS or its WPDC. So, for that and other reasons, the FOCA switched tactics and returned to a straight-on fight with the FISA using its tactic of enforcing the contracts in place to allow its members to participate within the new FIA Formula 1 World Championship. The FOCA made it clear that it no longer represented the interests of the Alfa Romeo, Renault, Ferrari, Osella, and Talbot Ligier teams with Toleman as a new team never having been associated with the FOCA. The FOCA continued to maintain the position that the ban on sliding skirts was illegal and that it intended to continue using them in races.

After barely a month's existence, the FOCA pulled the plug on its WFMS. One reason was that it was suggested that the contracts that FOCA had in place did not mention the WFMS or its WPDC. So, for that and other reasons, the FOCA switched tactics and returned to a straight-on fight with the FISA using its tactic of enforcing the contracts in place to allow its members to participate within the new FIA Formula 1 World Championship. The FOCA made it clear that it no longer represented the interests of the Alfa Romeo, Renault, Ferrari, Osella, and Talbot Ligier teams with Toleman as a new team never having been associated with the FOCA. The FOCA continued to maintain the position that the ban on sliding skirts was illegal and that it intended to continue using them in races.

As the talks continued, the South African Grand Prix was run on its scheduled 7 February date. The race was supported by the FOCA teams - and Goodyear! - running their cars with sliding skirts. Carlos Reutemann won for Williams with Nelson Piquet (Brabham) second, followed by Elio de Angelis (Lotus), Keke Rosberg (Fittipaldi), John Watson (McLaren), and Riccardo Patrese (Arrows). This race was later to be declared "outside the championship" and the results and points were null and void.

As the talks continued, the South African Grand Prix was run on its scheduled 7 February date. The race was supported by the FOCA teams - and Goodyear! - running their cars with sliding skirts. Carlos Reutemann won for Williams with Nelson Piquet (Brabham) second, followed by Elio de Angelis (Lotus), Keke Rosberg (Fittipaldi), John Watson (McLaren), and Riccardo Patrese (Arrows). This race was later to be declared "outside the championship" and the results and points were null and void.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 8

Atlas F1 Special

The Cult of a Personality, III

The FIASCO War: the Finale

The Return of the Boss

Columns

The Fuel Stop

Bookworm Critique: the 100th Column

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |