Atlas F1 Technical Writer

Changes to the regulations mean that the teams will be penalised for using more than one engine per driver per two race weekends from the season opening Australian Grand Prix, as well as tyres that must survive qualifying and a race. Atlas F1's technical writer Craig Scarborough reviews the changes, and how the teams will cope with the new rules

Tyres

There are a number of contradicting requirements from the tyres now while, outwardly, the rules have been seen as nonsensical and negative to the sport. They have in fact been cleverly worded to ensure the teams have to compromise at every step of the race weekend; this caps speeds quite efficiently, and penalizes bad driving.

The drivers will now get two sets of tyres on a Friday to choose between (the prime and option tyres from their suppliers); at the end of the day one set will go back to the supplier and the team will get two additional sets of their preferred tyre choice. One of these sets will be used for both qualifying and the race, with the other set as a spare which cannot be used unless the race tyres and Friday tyres get damaged - any damage to the drivers' race tyres will see the well-worn Friday tyres fitted before the fresh set. It was suggested that tyres could be switched from one side to the other in a race situation; this is not allowed, as it constitutes a tyre change.

The effect of the new tyre rule will see the teams changing the set up of the cars and the electronics to reduce wear. While the fastest lap may be much faster than the teams actually achieve, the pace will be set by the rate of tyre wear or degradation. As these tyres will last through qualifying without any set up changes allowed in parc ferme, outstanding second qualifying times could be the result of an over-ambitious or strategic tyre strategy. Tracks with poor overtaking that are easy on tyres could see more risky strategies employed.

Suspension geometry is the first factor in tyre wear - putting too much camber (angle) onto the wheels will wear the tyre unevenly, resulting in a worn outer tread. Secondly, traction control (TC) is a great factor in tyre wear - the electronics can keep a tyre right on the edge of traction and slip for a longer period than any driver is capable of, so the tyre is constantly at the maximum wear rate during acceleration. Calming the TC down for the race to preserve the tyres will be common place, with the exciting option of the drivers turning up the TC to maximum to aid overtaking another slower car, who is probably nursing its tyres.

Tyres can be changed during the race - that in itself is not banned, but the penalty of a drive through ‘punishment' (the driver will not be allowed to refuel on the same stop) makes this option a last resort rather than a strategic choice. Should a circuit see lap times drop off dramatically, a driver could find himself able to regain the time lost in the pits (one pit stop and another drive through) by capitalising on fresh tyres, but the FIA would take a dim view on such tactics, and consider penalties or subsequent clarifications on the rules.

There could of course be a unique set of conditions, where tyre wear is at dangerous level or something has been proven to be cutting the tyres. The team principals have stated they will take the drivers safety as the primary concern and bring their cars in.

With testing being so cold and Barcelona being re-surfaced, the teams have found it hard to evaluate tyres. To make the tyre last longer, harder compounds are being used - these do give very good and durable grip, but getting the tyres up to working temperature has proven difficult in testing with the low ambient temperatures. As a result the first hot races could see teams with set ups that are not kind to their tyres.

Aerodynamics

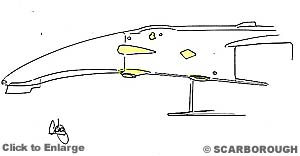

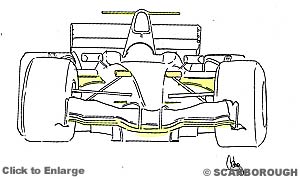

With the second tranche of rule changes aimed at reducing downforce, the cars will be subtly different this year. The front wing has been raised 5cm, the rear wing moved forwards 15cm and the diffuser height restricted at 12.5cm. This has slashed downforce by around 30%, with the loss being split equally between the three changes.

With all the teams except Ferrari, Minardi and Jordan releasing all new cars, some of the design trends are quite apparent. What has been a surprise is that no team has gone for a really radical approach - the higher front wings led me to expect to see noses and chassis being raised to clear the front wing flow, but this hasn't proved necessary, nor has the need for previously unseen supplementary wings designs. As a result the cars are developments of design ideas seen over the past few years, and most cars bear a strong resemblance to their predecessors.

These solutions lead to their own problems - the lower centre section needs to merge its wake with the less dramatic outer sections, with some of the flow even moving sideways across the wing at the steepest transitions. The increased wing angle has several problems - the wing needs to sit lower on the endplate, reducing its sealing effect, and the steep angles send a lot of flow upwards over the suspension and sidepods, upsetting the rear wing. Additionally, the steep wing angles send stronger vortices around the front wheels again, upsetting the flow to the rest of the car.

The resulting solution seems to be centering on a single design, using two or three elements - a deeply dished centre span and slightly raised outer tips. This provides a compromise between downforce and tidy flow over the rest of the car. How the teams arrange the nose above the wing is an area of great contrast - Ferrari have made their nose low and bulbous to follow the shape of the front wing, while Williams have gone for a high, narrow nose to remove it from influencing the front wing. High or low, narrow or wide, the shape is a small part of the cars aerodynamic effectiveness, and certainly no one solution is better than the others.

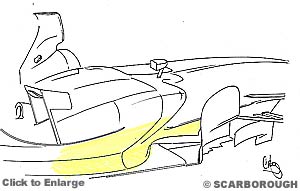

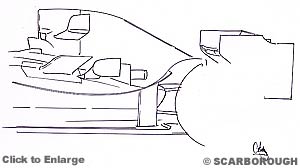

The offset of these bargeboards is their effect on the flow heading around the front of the sidepods. In the past teams have used a sidepod fin, mounted low and wide in front of the sidepods - this collects the flow heading in various directions, routing it to where the designer wants it to go. The net result is the flow under the floor is kept clean, and the messier flow is sent around the lower half of the sidepods. These fins have been reduced in size, now only forming a triangular fin jutting from the outer corner of the sidepod floor.

Teams like Sauber and McLaren have taken this shaping to an extreme, with the section under the drivers legs blending straight into the lower half of the sidepod. This results in the cooling inlet being moved higher up and, in Sauber's case, being more horizontal than vertical. This can appear to form a smaller inlet, but it is largely an optical illusion.

The ‘coke bottle' area has been reduced to slimmer and lower dimensions, an effect made more dramatic by the higher sidepod fronts - most are now near cockpit height (Williams excepted), with the sidepods needing to drop dramatically to wrap in tightly near the gearbox. This shape actually creates lift, but the resulting improvement in net flow to the rear wing increases the total downforce produced.

With such tight shaping of the sidepods cooling has to be tackled more innovatively. Curiously Renault has returned to upright radiators, rather than the book-folded versions in 2004. A remarkable degree of convergence in design sees a large chimney working in conjunction with the winglet, with louvered panels optimising the rest of the cooling.

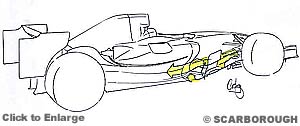

With so much cooling flow being exhausted directly above the radiators, the rest of the sidepod merely acts to fare in the exhausts. As a result the teams are now wrapping the exhausts in as tightly as possible, moving the main jumble of pipe-work forwards towards the space behind the radiators.

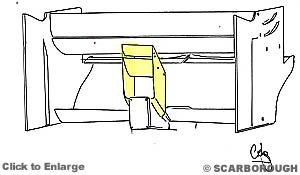

By the time the flow over the car reaches the gearbox it has been messed up by every single preceding part on the car. While efforts are made to keep the flow as clean as possible the quality, speed and direction of the flow ahead of the rear wing is far from ideal. Since the two-element rear wings were introduced last year most teams have made greater strides to pre-condition the airflow ahead of the rear wing. The better the on set flow, the more aggressive the rear wing can be, allowing it to produce more downforce.

We now see mid wings on the roll structure and shelf wings between the rear wheels being used at most circuits. These are not wings used for their own downforce, but devices to direct the flow in a more sympathetic way for the rear wing to deal with. This year Williams have adopted two large mid wings, while McLaren have created the so-called horn wings as new takes on the conditioning solutions.

Under the car the flow passing along the flat floor will be pulled through by smaller diffuser tunnels - as their absolute height and length is limited, teams have to put in a very steep initial gradient at the start of the tunnel to kick-off the diffusing effect as aggressively as they can. This risks stalling if the flow under the car is not as clean or in the direction as expected, with immediate loss of half of the car's rear downforce.

Engines

The teams now have to make their engines last two race weekends, rather than one in 2004 - this moves engine life from 800 km to nearly 1500 km (932 miles). It was the FIA's aim to use this rule to reduce costs and limit power, but as it is the last year for V10 engines before the V8 rules the teams have probably spent more money developing these units for just one year of competition. Power reduction is also a target missed by the rules; most teams aim to have the same power and rev limits as at the end of 2004.

The horsepower of the first engines raced this year will simply be a plateau on the ever-rising curve of power outputs from the V10 units. The engines used in Australia will also be used at Malaysia before being replaced for Bahrain. At the end of the first race, the engines will be sealed - this comprises lock wires and seals, as well as a blanking plate over the exhaust ports, which will only be removed by the FIA at the start of the next race weekend.

The team will keep the engines in their possession between races, with internal inspection only allowed through the normal apertures in the engine, i.e. with endoscopes through the inlet ports, oil ways and exhaust port (through a hole created in the blanking plate). The team cannot fire the engine up in between races, but can turn it over - the hole in the exhaust blanking plate allows the compression to be released through the exhaust ports.

Making the engines last twice the distance has been a three part process - detail design made sure parts are as light as possible and still as strong as their use demands, ahead of quality issues to make sure every component is as well made as its design dictates, and lastly the oil system has been revised with new oils and circulation to ensure bearings are cooled and lubricated, to minimise wear. As a result the majority of teams have evolved their 2004 engines, rather than going for a new design.

Gearboxes

Although engines now have to last 1500 km, gearboxes are under no such restriction. Development of gearboxes has been focused on size, weight and shift speeds. Last year BAR ran a full carbon fibre case with no reliability issues for the full season - the weight saving and stiffness gains were said to be significant. Others teams tended to centre on cast titanium, maintaining a very short casting and light overall weight, and citing advantages of greater repeatability of the casting and the ability to farm the work out to specialists, resulting in composite department production schedules not being bogged down with complex gear cases.

Shift speed has been getting shorter annually as a result of detail development to otherwise conventional gearboxes. Formula One gearboxes use longitudinally mounted gear clusters with two shafts, while a motorcycle-style selector drum operates the gear change forks, with the gears engaged using dog rings (unlike road cars, which now often use synchromesh). The actual process of a shift is more than the selection of a gear; the gearbox needs to sequence the throttle and clutch to unload the gears, then deselect the old ratio and select the new one, then release the clutch and throttle to match road speed to engine revs.

This whole process takes around 40 milliseconds - the reduction in shift speed is not directly related to lap time, as the car is not accelerating during the shift but is still moving, hence lopping 10 milliseconds off the shift will not result in a 10 millisecond lap time improvement. Lap time simulations predict around 0.2 of a second could be gained by maintaining drive when shifting gear, i.e. a zero shift speed - this is a significant gain if the technology to create it does not offset too much of the theoretical gain.

There are some technologies that would allow a continuous drive during shifts, such as CVT (constantly variable transmission) or double clutch arrangements, but these are effectively banned by the rules demanding no more than seven forward speeds.

The current sequential shift and dog engagement can be made to shift quicker - the problems occur when the shift is faster than the engine's ability to slow down enough to match road speed with revs. When this occurs the driver feels a jolt as the slower moving gearbox suddenly decelerates the engine. This upsets the car's balance, sending unwanted loads and oscillations through the engine and gearbox, potentially leading to failures. Currently, despite the V10 engines very low inertia, the gear engagement speed is often faster than the engine can handle.

BAR have admitted to running a new shift mechanism, termed ‘seamless shift' by the media albeit refuted by BAR. They have not released any information about the system other than that the FIA have accepted its legality and confirmed that at least two other teams will use similar technology in 2005. One of the guiding principles of the FIA's gearshift rules is that the car must see some break in power transmission during shifting; otherwise the seven forward speed rule is not upheld, as the car is effectively seeing one long shift formed of seven seamless individual shifts.

I would imagine the new shift technology uses some variation on the dog engagement rings, possibly discarding dog rings for clutches that allow a gear to be engaged and wait for the engine revs to rise once road speed is matched. This would mean the gearbox consists of seven gear clutches, with one conventional clutch for starts but thereafter unused in shifting. Hopefully more information on this exciting technology will be made public during the year.

Winter Testing

Winter testing was focused on Valencia, Spain, a small, tight track in comparison to other frequently used test tracks. Barcelona has also been used, but it was closed and resurfaced to rid the track of some of the worst bumps - it has subsequently been a virgin surface that has provided little real data in preparation for the GP or against other test tracks.

Additionally a cold, bitter winter in Europe has seen very low temperatures and even snow - in contrast the opening, hot races will challenge the teams preparations. Some teams with tighter sidepod shapes have already shown scorch marks where exhausts touch the bodywork - adaptations to cooling arrangements will probably be seen in Malaysia.

Team by Team

Ferrari

Running with the aim of racing their revised car until the opening races of the European season the car has, by the team's own admission, reached the limit of its potential. Simplistically the F2004M is a F2004 revised with new wings, floor and electronics - as a result the team have a lot of testing under their belt with the interim car, as well as the full experience of it racing last year.

In concept the car is little different from its predecessor, aside from Ferrari's novel chin wing, which acts much like pre-conditioner wings for the rear wing. During testing the team have been able to focus more fully on tyre testing, as the rest of the car is such a known package. The interim car's pace appears to be at least competitive with the fastest of the new cars, but should it start to fall behind on pace over the opening races the team have no fall back position, with the new car yet to launch and the F2004M developed to its maximum. It appears Ferrari is gambling on a risky hand this year.

BAR

After a successful 2004 and the early release of the 007, the team's testing performances have been disappointing. Engine reliability and pace have been the key issues; this despite the team running the interim concept car since December to prove the engine and gearbox combination. Honda now suggests the engine is at a level where it will last the double race weekend, but it has to be presumed the RPM limit and power output have been affected by the problems.

Additionally the drivers are not happy with the car's handling - the car has seen some new developments to combat this, including a revision to the aggressive front wing seen at the car's launch. The team has been running a 2004 spec front wing in testing, and has now also produced a three element front wing without the very long chord central section. These problems will probably hamper the team's first races, but not their potential performance over the balance of the season, as updates progress at the launch of the European season.

Renault

Sensitive handling, and a lack of power, stymied Renault's 2004 season - this year in testing Renault has shown they have reduced both deficits to their rivals. Outwardly the R25 is little different from its predecessor, but small details like the tidier sidepod cooling arrangement and the V keel suggest there wasn't much else wrong with the concept of the R24. Both drivers commented that the R25 was good for high-speed grip and low speed balance, while setting strong lap times in the process. The team seems to have overcome the lack of downforce and lack of grip from the new harder tyres, producing a well-balanced car.

Renault is still running the 72-degree engine, unlike the otherwise universal 90-degree layout of the engine suppliers. The layout doesn't appear to create the same problems as the wide-angle unit used up to 2003. Their use of a six-speed gearbox appears to suggest they are still lacking in power, albeit with a broader rev range. This power delivery worked well for the team in 2004; the advantages in traction, with the flatter torque curve, overcame the other teams' peakier response.

For the early season, while their rivals get up to speed, Renault should be a strong contender for podiums and even race wins.

Williams

Over the last year Williams have been commissioning their second wind tunnel - heading this project was Loic Bigois, who is now the team's head of aerodynamics. The new tunnel runs a larger scale model than the older version (60% against 50%). The new car's development was completed in both tunnels, working with different scale models, and without the new tunnel having produced parts for the 2004 car program. As a result, when the full-sized car was run in the tunnel, it didn't correlate to the figures expected.

Assuming the car doesn't have any other faults in the mechanicals or engine, the team again need to ramp up their aero program. It takes time to design new parts on CAD, run the CFD code on them and prove them in the wind tunnel or on track. Once again we will see Williams playing a catch up game with their rivals as the season unfolds.

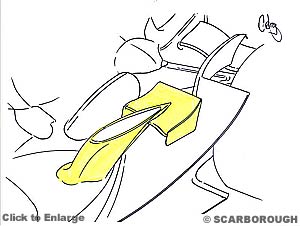

Williams have already been trying quick fixes to recoup the lost downforce and lap times. Bigger gurneys on the rear wing, as well as the untidy mini-wing mounted to the rear light (highlighted in yellow). This little wing works simply to add downforce at the rear, and being in the wing's shadow produces little drag. It sits within a small free zone in the bodywork rules, exploited by Renault last year with the un-raced winglet used at Monaco, albeit mounted above the rear wing.

The team has also run a new diffuser tunnel shape from the launch version, with the lower half of the centre tunnel being curved in. Other detail developments include a small strut to reinforce the flip up and direct flow away from the floor opening around the rear wheels.

McLaren

Launched with little fanfare, the MP4-20 is McLaren's closest design concept to its rivals. Many of the solutions have moved towards the design trends described above, although Adrian Newey and his team still retain a strong sense of individualism - for example the car eschews the single keel format of all of its rivals, yet moves a step away from the twin keel designs started with the MP4-17 - the front lower wishbone picks up on the lower edge of the monocoque, with the forward mounting to a vestigial keel in the form of a bump on the monocoque to make the mounting low enough for the desired suspension geometry.

Since the car started testing it has proven quick and reliable and, with progress being made, some of the team's new aerodynamic tweaks have emerged. These include the so-called horn wings - these act in the manner of mid wings as used by most teams, but the format of the device is a right-angled fin. The inner edges of these surfaces wear small gurneys - the effect of the fin and gurney combination would be to turn the flow inwards over the engine cover, producing a higher pressure over the centre of the wing. The McLaren design team has found an alternative approach to the same issue affecting other teams.

Sauber

With the huge resources of their wind tunnel and super-computer powered CFD program, both united to Ferrari engines and Michelin tyres, Sauber were looking to be in a strong position this year. But by the teams own admission the car has a flaw - this hasn't been elaborated on, and could be mechanical or aerodynamic, but the car hasn't met their expectations.

In testing the car has dropped the bi-plane front wing arrangement, seen at its first tests, and the 2004 spec front wing has been replaced with a new triple element front wing, following the fashion for deep central curvature. Hopefully the problems are easy to overcome with new parts and not major redesign, but the team's early season will no doubt be compromised by deficiencies leaving them trailing what could otherwise have been a strong position among the Michelin runners.

Red Bull

While we now have to say Red Bull when we used to mean Jaguar, the newly re-christened team have been solidly working on their 2005 program. The new for 2005 RB1 has been setting good testing times, and comments from Cosworth claim the new engine is their best yet and a step forward over their recent line of engines.

It's too early to be sure if these signs are proof of a competitive 2005, but a positive start to their campaign is a welcome change from pre-season bad news in years past. Externally the car has differed little from the launch specification.

Toyota

There have been mixed signals emanating from the Toyota team - some testing times have eclipsed other runners, but there have also been tales of poor handling from the drivers. With two professional and experienced drivers I would take their comments quite seriously - the car has proven to lack rear downforce, and as a result it wears it rear tyres too quickly.

Fortunately these comments were made before the new aero package was released, and there are yet more updates due for Melbourne, which is typical of Mike Gascoyne development methodology.

The small nose fins are akin to the versions Williams ran last year while trying to get the walrus nose to work. Moreover, the shoulder wings mimic Jordan's 2004 mid-season rework - these changes suggest the team is trying to redirect the up wash off the front wing from going over the sidepod tops. At this early stage such a proliferation of devices look bad for the team's aerodynamic efficiency.

Jordan

With the EJ15 being a lightly modified EJ14 with a Toyota engine, the team has been able to focus their testing on electronics integration, trying launches, traction control and checking the anti-stall and pit stop exit systems. This has also been practice for the team's two new drivers, inexperienced in Formula One and with little track time before their first race.

Testing has shown the car to be far off the pace - this could be a reflection of the car's inherent pace, but also of the testing program undertaken as well as driver pace. Whichever, the team have only Minardi as realistic opponents

Minardi

Minardi announced a radical concept for their definitive 2005 car, although this won't be released until the eve of the European season. Rumours suggest that Minardi have found a new sidepod treatment which will be very different from their opposition, and the team have also boasted the new car is the first clean sheet chassis design since the PS02.

In the mean time the 2004 car will be used instead - this has not yet appeared with a full 2005 aero package, although a raised front wing and revised rear wing have been run, but I have not yet seen a new diffuser to meet the new regulations. Apparently Minardi have requested permission to run their old car for the opening races - this has rightly been met with opposition from Ferrari.

Yet again we will see a team writing off the opening races to race a new car at the start of the European season - should the new car be a success the team may be able to beat Jordan, but most likely they will remain consigned to the back of the grid.

This season should prove to be a close competition - new rules affects every area of the car, from long life tyres and engines to now-crippled aerodynamics. Such major changes have seen a intense testing period, with teams running both modified 2004 cars and releasing their 2005 early enough to complete some testing. Three teams have effectively rolled out their 2004 cars revised to the new rules for the opening races - testing suggests this route may be a bigger risk this year as the 'made for 2005' cars are meeting their potential early in testing, while the modified 2004 cars are already at their limit.

With tyres now having to last two qualifying sessions and the whole race it would be reasonable to assume that the tyres will be rock hard and give no grip. While the tyres are running a harder compound, the drivers have found they last a surprisingly long time, with many drivers putting in their fastest times in the last laps of a race distance test. This development will still see tyres punished at hot or abrasive tracks, and teams will have to manage their tyre use carefully.

With tyres now having to last two qualifying sessions and the whole race it would be reasonable to assume that the tyres will be rock hard and give no grip. While the tyres are running a harder compound, the drivers have found they last a surprisingly long time, with many drivers putting in their fastest times in the last laps of a race distance test. This development will still see tyres punished at hot or abrasive tracks, and teams will have to manage their tyre use carefully.

As the raised outer span of the front wing loses downforce through the lack of ground effect, the teams have a big problem regaining this downforce. There is quite a tight envelope into which to fit the front wing - the outer sections must fit within the endplates profile, while the 50cm centre section can be as low as the floor but no higher than the rest of the wing assembly. Clearly the teams have made the most of the lower central span, cranked up the front wing angle and lengthened the chord as much as possible.

As the raised outer span of the front wing loses downforce through the lack of ground effect, the teams have a big problem regaining this downforce. There is quite a tight envelope into which to fit the front wing - the outer sections must fit within the endplates profile, while the 50cm centre section can be as low as the floor but no higher than the rest of the wing assembly. Clearly the teams have made the most of the lower central span, cranked up the front wing angle and lengthened the chord as much as possible.

The stronger wake from the front wing bargeboards leads to a convergence of design with smaller forward placed bargeboards, often consisting of two elements: a large inner board and smaller outer forward vane. The forward placement of these bargeboards collects the front wing's flow more effectively, and also moves the aerodynamic centre of pressure forwards, improving front downforce.

The stronger wake from the front wing bargeboards leads to a convergence of design with smaller forward placed bargeboards, often consisting of two elements: a large inner board and smaller outer forward vane. The forward placement of these bargeboards collects the front wing's flow more effectively, and also moves the aerodynamic centre of pressure forwards, improving front downforce.

To further improve the effect sidepods are now undercut, leaving a flatter floor area on the front corner of the sidepod. This year this design is almost universal on new cars. The undercut eases the path around the sidepods for the flow passing under the nose and chassis, reducing drag, as there is less frontal area, which improves flow quality over the rest of the car.

To further improve the effect sidepods are now undercut, leaving a flatter floor area on the front corner of the sidepod. This year this design is almost universal on new cars. The undercut eases the path around the sidepods for the flow passing under the nose and chassis, reducing drag, as there is less frontal area, which improves flow quality over the rest of the car.

The chimney and winglet combination works effectively as the airflow speeds up directly in front of the winglet - this pulls hot air from the chimney through the winglet before spiraling to the outside of the rear wing. This effect makes the chimney more efficient than if it were run alone. Grills are now proliferating around the rearmost parts of the sidepods, which are more effective than a single large opening as they smooth the messy air passing through the sidepods, flattening it out to pass over the lower rear wing. This does create a small downforce penalty, but as these grills are only the secondary provider of cooling outlet they are only used to tune the cooling to the track. The rest of the time they are run as closed as much as possible.

The chimney and winglet combination works effectively as the airflow speeds up directly in front of the winglet - this pulls hot air from the chimney through the winglet before spiraling to the outside of the rear wing. This effect makes the chimney more efficient than if it were run alone. Grills are now proliferating around the rearmost parts of the sidepods, which are more effective than a single large opening as they smooth the messy air passing through the sidepods, flattening it out to pass over the lower rear wing. This does create a small downforce penalty, but as these grills are only the secondary provider of cooling outlet they are only used to tune the cooling to the track. The rest of the time they are run as closed as much as possible.

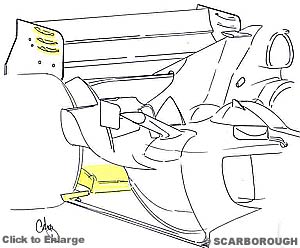

Given the lower diffusers and forward mounted rear wings the lower wing has less ability to interact with them - last year the combined effect of the upper wing, lower wing and diffuser created more downforce than the parts individually. Subjectively, the teams now appear to be trying to get the lower wing working with the diffuser to regain the lost downforce, with shapes sweeping forwards and down to get as close to the tunnels as possible. BAR and Toyota have lightened their lower wings by taking away the load bearing task, instead installing a supplementary vertical support for the upper wing.

Given the lower diffusers and forward mounted rear wings the lower wing has less ability to interact with them - last year the combined effect of the upper wing, lower wing and diffuser created more downforce than the parts individually. Subjectively, the teams now appear to be trying to get the lower wing working with the diffuser to regain the lost downforce, with shapes sweeping forwards and down to get as close to the tunnels as possible. BAR and Toyota have lightened their lower wings by taking away the load bearing task, instead installing a supplementary vertical support for the upper wing.

Despite both conservative and radical approaches to design, several new Williams have disappointed the team with their pace over the last few years. This year's Williams appears outwardly to have all the right shapes and elements, yet it has now been made clear that, even by the time the car was launched, it was flawed. The team has disclosed that the car lacks downforce - this was not a result of failing to set the right targets, as per last year, but rather the accuracy of their measurements.

Despite both conservative and radical approaches to design, several new Williams have disappointed the team with their pace over the last few years. This year's Williams appears outwardly to have all the right shapes and elements, yet it has now been made clear that, even by the time the car was launched, it was flawed. The team has disclosed that the car lacks downforce - this was not a result of failing to set the right targets, as per last year, but rather the accuracy of their measurements.

This improves the load path from wishbone to chassis, whereas the keel passed the load through an offset path, requiring a lot of weight in carbon fibre reinforcement for the requisite stiffness. Theoretically McLaren now have the underside of their nose with the clean aerodynamics of a twin keel and the light weight and stiffness of a single keel.

This improves the load path from wishbone to chassis, whereas the keel passed the load through an offset path, requiring a lot of weight in carbon fibre reinforcement for the requisite stiffness. Theoretically McLaren now have the underside of their nose with the clean aerodynamics of a twin keel and the light weight and stiffness of a single keel.

Other detail development seen on the car in testing has been the reinstatement of the sidepod winglets (not on the launch version of the car) and a wide vane between the floor and flip up - this should both reinforce the flip up and turn the general airflow away from the opening around the rear wheels. On the strength of their testing performance, and the inherent design of the MP4-20, McLaren will be a leading challenger amongst the Michelin runners this year.

Other detail development seen on the car in testing has been the reinstatement of the sidepod winglets (not on the launch version of the car) and a wide vane between the floor and flip up - this should both reinforce the flip up and turn the general airflow away from the opening around the rear wheels. On the strength of their testing performance, and the inherent design of the MP4-20, McLaren will be a leading challenger amongst the Michelin runners this year.

First run in poor weather, the new aero package consists of a new front wing, nose fins and shoulder wings. Taking something from many other teams, the new package looks a bit disjointed. The front wing uses an unusually wide U-shaped central section, with almost horizontal outer spans and now common flicked up outer edges. The wings' unusual profiles create distinct junctions between each different shape, but these also align with the turning vanes, which efficiently split the very different flows of each section.

First run in poor weather, the new aero package consists of a new front wing, nose fins and shoulder wings. Taking something from many other teams, the new package looks a bit disjointed. The front wing uses an unusually wide U-shaped central section, with almost horizontal outer spans and now common flicked up outer edges. The wings' unusual profiles create distinct junctions between each different shape, but these also align with the turning vanes, which efficiently split the very different flows of each section.

Notwithstanding the mountain they have to climb in the time available, new developments have appeared over the car's first tests - the floor has been revised to a full 2005 specification, with the in-filled tunnels of the first EJ15 being replaced by proper low tunnels, and the floor has also been given a turning vane to deflect flow from the opening around the rear wheels.

Notwithstanding the mountain they have to climb in the time available, new developments have appeared over the car's first tests - the floor has been revised to a full 2005 specification, with the in-filled tunnels of the first EJ15 being replaced by proper low tunnels, and the floor has also been given a turning vane to deflect flow from the opening around the rear wheels.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 11, Issue 8

2005 Season Preview

The Atlas F1 2005 Gamble

The 2005 Drivers Preview

The 2005 Teams Preview

The 2005 Technical Preview

Regular Columns & Articles

F1's Tobacco Addiction II

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |