|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

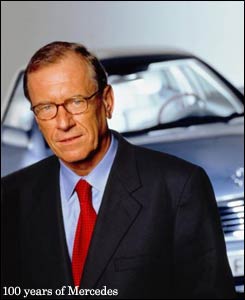

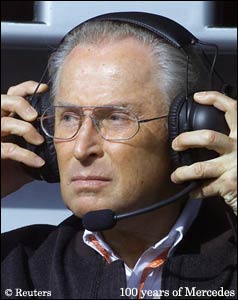

the death of Werner Niefer and the arrival and departure of Helmut Werner. An authentic survivor, Jurgen Hubbert was always willing to support the company's motor sports participation when it was not against its declared policy.

Stuttgarter Hubbert had watched the racing on the old Solitude circuit near his home town in the 1960s. But his importance to the Mercedes-Benz competition effort was that he was not a racing enthusiast. "He was never a 'fan'," said Mercedes racing director Norbert Haug about his boss, Hubbert. "He saw it as a marketing tool, as a means of presenting the brand. Thus motor sports never became a 'toy' of the management." Rather, it was entered, in the 1990s, as part of a planned marketing strategy. "We were all convinced that we could do something for the brand with motor sports," added Haug. "We thought we could. And our motor sports have had a big impact, especially among the young." In 1997, for example, the McLaren-Mercedes was featured on screen for more than 20 of the 244 Formula 1 television hours broadcast in Germany. In the same year the CLK-GTR was the on-screen star for 9 of 60 hours broadcast. In the PPG CART series an average of 140,000 spectators at each race saw Mercedes-Benz on its way to an engine manufacturers' championship. |

The Original Benz |

|

|

The partners came through. Sauber did his job in the 1980s with the rebirth of the Silver Arrows in Group C. AMG achieved excellent results in the all-important German market with its C-Class racers. And with Ilmor, Penske and McLaren as partners, Mercedes-Benz won the Indy 500 in 1994, and in 1998 and '99 again scaled the heights of the Formula One sport that it had once dominated.

Only in the late 1980s did Mercedes-Benz renew the strong motor sports commitment that it suspended after its dominant year of 1955. For three decades, apart from some rallying with standard cars, its great racing reputation was neglected. In both the human and technical senses it was difficult to bridge the gap. But the spirit never died. Determined and enthusiastic people kept it alive. When it was necessary in their view for the welfare of the firm they 'did good and spoke not of it'. The gap was bridged. And when it came time to make a return, suitable partners were ready too. The partners knew this was no sinecure. They too needed to perform 'up to Mercedes-Benz standards'. Many knew the legend; some knew the history. Daimler-Benz had faced and mastered virtually every challenge that the world of motor sports had to offer. Was this to be a burden to them, or a benefit? The results on the track gave the answer. |

The Original Daimler |

|

|

defeat." This could and should remain the watchword of Mercedes-Benz in motor sports.

The skill and intuition of its managers, researchers, designers and engineers gave the assurance that the racing cars and the passenger cars bearing the Mercedes-Benz name were built to a very high standard that both had in common. This was the intellect of the company, its rationality. Racing was the soul of Daimler-Benz, its emotion. Both intellect and emotion are needed to bring to completeness not only a person but also an organization. At the beginning of the new millennium Daimler-Benz - now DaimlerChrysler - was again complete. |

|

|

| Karl Ludvigsen | © 2007 autosport.com |

| Send comments to: ludvigsen@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |