|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

regular Georg Scheerer were not available. Whether this would have made a difference is difficult to say, but the Rennabteilung met reality face to face Argentina. While the three cars lined up on the front row of the first race, it already evident that things just might go their way.

At the drop of the starter's flag, the two-litre supercharged Ferrari of Froilan Gonzalez rocketed off the grid with the three silver cars and harried the team until he rocketed past Lang and into the lead on the 23rd lap. Gonzalez was forced to make a quick pit stop due to a fuel leak, but caught and passed Lang once again on the 38th lap, leading the final seven laps. Although Lang, Fangio, and Kling were 2nd, 3rd, and 6th there was no doubt that they had been defeated in a manner thought almost inconceivable a dozen years before - although both Lang and Neubauer still remembered the Pau race of 1938. A week later, the second race was run. Fangio once again set on the pole with the his teammate Lang beside him. The Rennabteilung did a commendable job under the circumstances to rectify some of the problems noted in the first race. Although Fangio rocketed into the lead at the start, engine troubles caused him to drop back on the second lap and retire for good after 16 laps. Lang held the lead, but was soon passed by Gonzalez. Lang struggled to follow the Ferrari and waved Kling past to take up pursuit. However, Kling was soon under attack from the Maserati of Carlos Menditeguy who was soon into second and after the leader, Gonzalez. However, a problem with the switch to the auxiliary fuel tank put Menditeguy out on the 36th lap. This allowed Kling and Lang back into 3rd and 4th places. For the second time in successive weekends Gonzalez defeated the German visitors. While the sting of defeat from the Argentine was still fresh and the realization that any foray into Grand Prix racing would require anew car, a new opportunity beckoned Neubauer and the Rennabteilung. The same meeting in June 1951 also gave the green light to a new sports car and a racing program for it. Designated the W194, it is remembered to history as the 300SL "Flugelturen" or "Gullwing," one of the true classic sports cars. The Gullwing was the product of Rudolf Uhlenhaut, a remarkable engineer who was only the blink of an eye slower than most of the works drivers. From the decision to start the program in June 1951, it took until only March 1952 to present the prototype to the press. |

||

|

four minutes at the end. Needless to say Herr Neubauer was not amused. In a performance that only be called masterful, Rudi Caracciola finished the race in 4th place. Lang retired after clouting a roadside obstacle and damaging the rear axle.

Several weeks after the Mille Miglia, the Gullwings were entered in the sports car race held in conjunction with the Swiss Grand Prix. Although the cars finished in the first three positions, the fourth car crashed after the rear brakes locked up, sending it into a tree. The driver was seriously injured, but while he recovered that was the final race for Rudi Caracciola. The next race was the famed 24 hour race at Le Mans. As the result of some "suggestions" about the possible interpretation of the regulations, three new Gullwings showed up with modified doors. Karl Kling and Hans Klenk teamed in one of the cars, Theo Helfrich and Helmut Niedermayr in another, and Hermann Lang and Fritz Riess in a third. Initially the cars featured an idea that was uniquely Neubauer: he asked for a pop-up panel - mounted on the rear of the roof - to assist with braking. While it was eventually abandoned for the race, it was an indication of the lengths DB and the Rennabteilung were willing to go in search of success. In the event itself, Neubauer laid out a detailed game plan that worked around an unanticipated problem with tire wear. The Continentals the team was using simply did not measure up, but Neubauer adjusted accordingly. When the Kling/Klenk Gullwing dropped out while in the lead when its generator failed, they joined the Continental crew in being the subject of Neubauer's withering glare. There was some anxiety about the Pierre Levegh (known to his mother as Pierre Eugene Alfred Bouillin-Levegh) Talbot-Lago still leading late in the race, but its oil consumption dramatically increased in the waning hours and subsequently a rod broke. Lang and Riess then swept into the lead and then won the race, with Helfrich and Niedermayr finishing second. In early August, the Gullwings made their next appearance, but also present were 300SL roadsters! For the sports car race at the Nurburgring, all the stops were pulled out. A new M197 engine was developed for the race, a supercharged version of the M194 straight-six in the roadster. Naturally, there was a class for the new car. It is interesting to note that testing of the engine included a drive of the Gullwing, equipped with the new engine, from Stuttgart to the Nurburgring, running 12 laps of the Nordscheife and then driving back to Stuttgart. It didn't miss a beat. To save you any doubt, the roadsters in the hands of Lang and Kling were one-two, with Riess and Helfrich three-four in roadsters. |

||

|

of spares, 300 Continental racing tires, and all the other odd bits and pieces that are needed for a five day, 1,945 mile race from one end of Mexico to the other. Neubauer later wished he had doubled the size of the expedition. Oh, they also obtained an airplane for Neubauer to supervise the race from the air.

The entries were for Karl Kling and his navigator Hans Klenk, Hermann Lang and his mechanic Erwin Grupp in Gullwings and American John Fitch with Eugen Geiger in a roadster. The fourth car was used by journalist Gunther Molter - hired on to handle PR and assist Herr Neubauer as required - as the team hack and whatever else it might be handy for. One decision Neubauer made prior to the start was not to challenge the Ferraris, particularly the rapid coupe of Mille Miglia winner Giovanni Bracco. After Lang hit a dog, Kling had a buzzard collide with the windshield - stunning Klenk - and Fitch joined the others in suffering tire problems, and this was only the first stage! Neubauer's strategy turned out to be correct, of course, and the cars simply hounded Bracco into submission, particularly after Mexico City where the literal weight of the DB effort began to tell. Although Bracco fought the good fight, he retired on the seventh stage when the differential finally cried enough. In the final stage Kling averaged an amazing 220 kmph. While Neubauer frantically struggled to keep up in his airplane trying to get Kling to slow down! Kling and Klenk were the winners - with now fashionable "buzzard bars" fitted to their Gullwing - with Lang and Grupp finishing second. Fitch and Geiger were disqualified when they stopped to solve a problem in the alignment of the front suspension and received outside assistance. They were running in third at the time. And then DB and the Rennabteilung disappeared until July 1954. However, the tide was already shifting and when the Rennabteilung returned to the circuits the role of Herr Neubauer was subtly different. In the 1952 and 1953 seasons, pit stops in Grand Prix racing began to shrink from several per race to perhaps one and even none. In the early months of 1954, this pattern repeated itself. However, what had not changed was the importance of preparation, organization, attention to detail, and teamwork, areas in which Neubauer was simply unequalled. What had changed was that more and more of the decisions concerning the Grand Prix team were being made by Rudolf Uhlenhaut. |

||

|

the Nurburgring while the Rennabteilung worked at preparing cars for their first appearance at Reims.

Neubauer, to be sure, was still the master of the Rennabteilung. And while the technical aspects of the operation were now more-or-less in the hands of Herr Doctor Engineer Uhlenhaut, let there be no mistake who was the Rennabteilung. Neubauer organized the details of the DB assault on the Italian GP grid. Neubauer oversaw the testing of the new cars, helped determine the size of the fuel capacity of the cars, and kept the pressure on the suppliers - such as Continental - to make sure that deadlines were met and that the product measured up to what the Rennabteilung demanded. For his team, Neubauer selected the Argentine Juan Fangio. Neubauer was aware that Gianni Lancia was also very interested in the former Alfa Romeo driver. Indeed, Lancia had been delighted with Fangio's performance in their sports cars during 1953 and offered Fangio a contract for the 1954 season to drive their new GP machine. However, when Neubauer made his proposal Fangio was quick to accept, even with the provision that DB might not run during the early events in the season. Negotiating with Fangio in his fluent Italian, they also discussed whether Fangio would sit out the season until DB entered the fray for a certain sum of money; or would he accept a reduction in that sum and be free to participate for another team until called to duty by Herr Neubauer? The latter was agreed upon and Neubauer moved on to other things. While Neubauer played a major role in the events of the DB assault into GP racing, it was, as mentioned, very different than the role he had played in the pre-war days. The scarcity of pit stops contributed and changes in the very nature of the GP art as now practiced conspired to lessen his role in the outcome of events. He did continue to rule the team with an iron hand when it came to personnel matters and also the actual conduct of the "expeditions" to the circuits. He was the organizational mastermind of the Rennabteilung and rarely left any stone unturned as the cars were prepared for competition. Few teams of the day could produce - almost as if by magic, a new windscreen to replace one shattered by a stone. |

||

|

but the drivers for this amazing about Northern Italy. There were three 300SLR cars built solely for the purpose of practicing for the race, with four new cars being built for the race itself. DB was determined to win the race and spared no effort to see that goal achieved. In a rare dry running of the race, Stirling Moss and his navigator Denis Jenkinson not only won the event, but shattered the record. Second was Juan Fangio. The 300SLR of Karl Kling, along with that of Hans Herrmann and Hermann Eger, retired from the race.

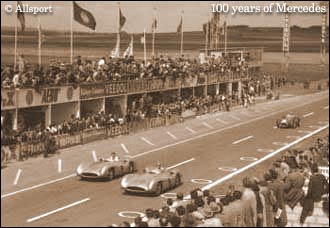

At the end of the month, the Rennabteilung entered three cars in the Eifelrennen at the Nurburgring. They finished one-two-four in the hands of Fangio, Moss, and Herrmann. However, the event was little more than a warm-up for the 24 Hours of Le Mans, an event in which the Rennabteilung was determined to repeat its 1952 success. The Rennabteilung entered three teams for the French race: Karl Kling and Andre Simon; Juan Fangio and Stirling Moss - an indication as to how serious they were about winning; and, John Fitch and Pierre Levegh. The "aero-brake" concept from 1952 re-emerged, but now in the form of a hydraulically-actuated flap - air brake - which the driver employed from the cockpit at places such as the end of the Mulsanne straight or going to the White House corners. Needless to say, DB came loaded for bear and was prepared to wage battle at several different levels to obtain victory. The start of the race saw Fangio in the cockpit for the initial stint. After a rather poor start, Fangio soon was at the front and having a hammer and tongs with Mike Hawthorn in a Jaguar D Type. This went on for over two hours. At about 20 minutes after six in the evening, Hawthorn was signaled in for his pit stop. As he approached the pits, he passed the Austin Healey of Lance Macklin and then abruptly dove into his pit, but due to his speed overshot it by 50-75 meters. Behind him, Macklin, taken by surprise by the sudden dive into the pits by Hawthorn, swerved to his left. In doing so, he avoided hitting the green Jaguar and averted a possible accident that could have had devastating effects in the pit area. Instead, he was now in the path of the 300SLR of Pierre Levegh. The Levegh 300SLR was traveling at speeds at least 75 kmph faster than the Austin Healey at this point in the very narrow pit straight. The 300SLR hit the Austin Healey and was launched into the spectator area across from the pits. Levegh only had time to thrust his arm skyward to warn those behind him before the silver car impacted the red car now in his path. Fangio, not far behind Levegh, managed to slow down and avoid getting collected up in the crash. Until his final days, the Argentine credits Levegh with saving his life by giving him that warning in his final seconds. The car flew in a shallow arc over the embankment and crashed nose-first into the crowd. |

||

|

members of the board, Moss and Fangio moved into first place with a margin of several laps over the second-placed car and the 300SLR of Kling and Herrmann was solidly in third.

When the DB board members finally gathered to discuss the situation, it took little discussion to agree to withdraw the team from the race. However, it did not vote to withdraw from racing at the end of the season, as most seem to think. Several weeks earlier, the board has already agreed in principle to terminate the GP program, but to continue the sports car program into the 1956 season. After the crash, it was now a certainty that the GP program would not be extended past the last race in the Championship, Monza. However, the board did announce that it would continue to participate in sports car events for the rest of the 1955 season and also in the 1956 season. The reaction to the Le Mans accident was both swift and inconsistent. France, Germany, and Switzerland canceled the national GP races and scores of other events were also canceled. Coming on the heels of a major crash at the Indianapolis 500 which killed defending champion Bill Vukovich, the outcry extended to both sides of the Atlantic. However, the week following the Le Mans race, the Dutch ran their GP at Zandvoort almost as if nothing had happened. The same for the British GP at Aintree, which Fangio and Neubauer conspired to give to the young Briton on the team, Stirling Moss. However, Neubauer made him earn it. There were 300SLRs entered for the Swedish Sports car GP, both with the Le Mans air-brake, for Fangio and Moss, who finished in that order. The next race for the sports cars was the Tourist Trophy in mid-September, then held on the Dundrod circuit in North Ireland. Three teams were entered: John Fitch and Stirling Moss; Juan Fangio and Karl Kling; and, Andre Simon and Wolfgang von Trips. While they finished in that order, the outcome was in doubt when Desmond Titterington gave the winning duo all they could handle until he dropped back. The Neubauer touch saved the day with his matching of the "horses for courses" and keeping the team informed where the opposition was - naturally he made it look effortless, but it was a tough race with much at stake. After the Tourist Trophy, Mercedes now trailed Ferrari in the Manufacturers' Championship, 16 to 19 points. The final round was the Targa Florio, run on the 72 kilometer Madonie circuit in Sicily. Neubauer returned to Germany to find that rather than compete in Sicily, the DB board wanted the next appearance of the 300SLRs to be in an important export market in South America - Venezuela. Enlisting Uhlenhaut and others within DB to his cause, launched a campaign on the DB director, Herr Konecke, to race in the Targa Florio. Needless to say, the director relented and Neubauer, with barely three weeks to field a team showed that his organizational skills were still top notch. In a flurry of activity the Rennabteilung delivered to the Sicilian docks the largest task force since Patton and Montgomery had visited the island: eight race cars, 15 (!) passenger cars, eight trucks, and 45 support personnel plus the drivers and their hangers-on! In the midst of preparing for the Targa, Neubauer was asked to nominate the events in 1956 he wished the Rennabteilung to participate in. Neubauer promptly replied with a list from which he was told eight to 10 would be selected. With that, Neubauer turned his attention back to the Targa. Mercedes not only needed to win, they had to prevent Ferrari from finishing higher than third; a Ferrari in second would result in a tie. Neubauer did not intend to tie the Championship. The team of Stirling Moss and Peter Collins gave Neubauer his win, despite a visit into the countryside and bopping a few usually stationary pieces of the scenery. Amazingly, despite heavy damage to the 300SLR, first Collins and then Moss lifted the car through the standings and wound up in first place at the end. The duo of Juan Fangio and Karl Kling clinched the 1955 Championship by finishing second with John Fitch and Desmond Titterington coming in fourth. By the skin of its teeth, the title belonged to DB. Neubauer returned to his hotel to savor the win and begin the preparations for the 1956 season. The announcement that DB was withdrawing from GP racing was already anticipated and known within the Rennabteilung. However, Neubauer discovered a letter waiting for him. In it he read that on 22 October at the annual press conference, DB would announce that not only was it withdrawing from GP racing, but from sports car racing as well. At the press conference, the racing cars were covered by shrouds and that was that. Neubauer ended his career as the manager of a victorious organization, the DB Rennabteilung, that was already the stuff of legends. Don Alfredo soon reduced his hours at DB and although he worked on a history of the Rennabteilung for several years, it was never finished. His legacy is secure in the annals of motor racing history. He is one of the true legends of the sport and one of its great characters. |

||

| Don Capps | © 2007 autosport.com |

| Send comments to: capps@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |