|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Wilhelm Maybach immersed himself in the total transformation of his company's product. Each change seemed to lead him to some other improvement, accounting for the extended time it took - by the standards of those days - to create the new model.

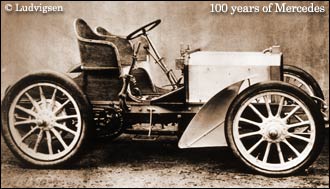

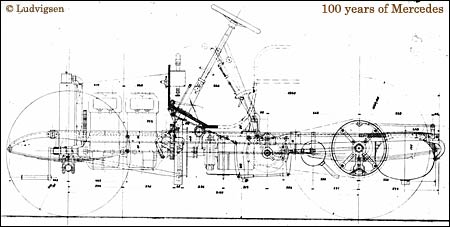

In its two-seater guise for competition, the new car kept 12-spoke artillery wheels like those of the 1900 Daimler, but spaced them farther apart on a 91.6 inch wheelbase and 55.2 inch track. The added length was used to lighten the front-wheel load by moving the engine to the rear and downward beneath a low, squared-off hood that set a design pattern for all front-engined cars to come. Maybach specified that the bearing shells of his new four cylinder engine were to be made of a light alloy invented by Ludwig Mach called 'magnalium', primarily aluminum with a 5 percent addition of the magnesium that was so readily available in Germany. Also figuring in the first experimental designs was partinium, a French alloy of aluminum with 7.5 percent copper, 2 percent zinc and 1 percent each of silicon and iron. Aluminum was used for the two-part crankcase, split horizontally on the crank centerline. The cylinders were cast in pairs of gray iron with integral cylinder heads instead of the removable heads of the Daimler-Phoenix. The H-section connecting rods and two-ring pistons were steel castings. Weight of the complete engine was held to 510 pounds, moderate for its output of 35 bhp at 1,000 rpm. Dimensions were 116 x 140 mm (5,973 cc) for the four cylinders, capped by T-head combustion chambers with 51 mm exhaust valves along the right side, 53 mm intakes on the left. Maybach made history by providing a second camshaft to open and close the intake poppets in place of the former suction-operated inlets. |

The Original Mercedes

The Original Benz |

|

|

At the center of the right-hand (exhaust) camshaft, a gear drove the low-tension magneto and the water pump, the latter delivering cool water directly to the top center of each cylinder pair. A gear at the front of the same camshaft turned a fan behind the radiator.

The cooling radiators of the Daimler-Phoenix cars had been assembled from a multitude of small circular tubes carrying air through a water-filled casing. Recognizing that the effectiveness of the radiator could be improved by increasing its heat transfer area, Maybach abandoned round tubes in favor of square ones of 5x5 mm which could be spaced more closely together. Maybach found room for 8,070 such square tubes in the 1901 Mercedes radiator, which was capped by a small separate header tank. This radiator could cool the 35-bhp engine with nine liters of water, half as much as had been needed in 1898 to cool a Daimler-Phoenix of only five horsepower. Virtually all other cars then, whether touring or racing, were still using finned-tube radiators. Wilhelm Maybach sought to banish clutch problems once and for all, in spite of the steady power and torque increases, with a radical new design known as the 'scroll' clutch, replacing the cone-type clutches that had been used hitherto. It mounted to the flywheel a spiral coil of strip steel, wound around a small diameter (about six inches) drum that was attached to the clutch output shaft. Through a lever attached to the rearward free end of this coil, a conical cam tightened or loosened its grip on the drum, as desired. The actuating geometry provided a self-servo effect: any clutch slippage tended to wrap the coil more tightly around the drum. |

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Original Daimler |

|

|

engines on separate subframes, Maybach narrowed his car's steel frame toward the front, just at the pedals, and attached the engine directly to it. The side members of the frame were shaped into a C-section from steel 4 mm thick.

Instead of using a rolled frame rail section, the DMG is credited with being the first to form the frame side members as pressings. This ultimately allowed far better proportioning of the frame depth to the varying levels of stress along its length. As well, the whole car was lowered by reducing the distance of the frame from the ground by 4.3 inches. Understandably stung by the criticism of the handling of the Daimler-Phoenix, Maybach sought to improve the steering as well as the weight distribution of the 1901 Daimler-Mercedes. He used a worm and nut steering gear, and inclined its column more to the rear from a more forward location below the toeboard. At the ends of the tubular front axle the steering pivots were deeply recessed within the wheel hubs to approach center-point steering. This had the aim of reducing the kickback through the linkage and wheel that was so violent, on some cars, as to break hands and arms. Braking was completely overhauled. The contracting bands used on the Daimler-Phoenix chain-drive countershaft were replaced by internal-expanding brakes inside the large rear wheel sprockets. These were applied by the hand lever through a toggle linkage. A pedal-operated band brake was added at the front of the gearbox secondary shaft, which directly drove (through a bevel-gear pair) the chassis-mounted countershaft of the chain-drive system. |

The Original Maybach |

|

|

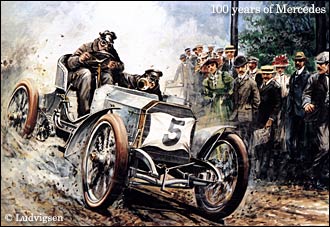

Factory driver Wilhelm Werner handled one of the several Mercedes cars that competed in the road race, hillclimb and standing and flying mile and kilometer events during Nice Week in March, 1901. The cars were, and looked, just finished.

Werner effortlessly won the 244-mile road race from Nice to Salon and back to Nice at an average speed of 36.0 mph and the La Turbie hillclimb at 31.9 mph. He was bested only by steam cars, still supreme over short distances, in the speed trials on the Nice promenade. His best speed over the flying kilometer was 53.4 mph. "So far," reported Wilhelm Maybach from Nice on 12 March, "the car has gone well in the Nice outings and we have been able to confirm this in various drives in the surrounding countryside. After longer trips, however, there are still defects which require improvement." Maybach prepared a list of the changes needed that included the following notes:

|

(Click Image to Enlarge)

|

|

|

The need for improvements to the clutch, already the source of controversy with Jellinek, was further confirmed by the initial testing and racing at Nice. New parts for it had already been made; Maybach asked for these to be sent to Nice with a mechanic who could install them to ensure that Emil Jellinek could compete with his car on 12 March.

Other spares coming from Cannstatt for the 1901 Mercedes were new types of ignition springs and various sets of gear wheels for all four forward speeds. A new reverse-gear idler was needed because reverse had been engaged by mistake; Maybach also asked for an improved latch to be designed to prevent unwanted selection of reverse.

Maybach's note was a reminder that not everyone intended to race his new Mercedes. "The cars for Essling and Rothschild must have heavier flywheels," he instructed, "because they are not racing cars." Another instruction hinted at the traffic conditions in the south of France: "Mr. Lubecki would like a siren installed on his car."

|

|

| The Mercedes successes at Nice were a boon to Emil Jellinek's sales efforts. According to historian Gerald Rose they "gave food for much thought to the other constructors, who saw in the extraordinary progress of the Cannstatt firm a menace to their existing superiority." Added the historian of the early Benz and Mercedes engines, K. Schnauffer, "No one would have thought it possible for a non-French motor vehicle to shake, let alone break, the dominant French position." The legend that was and is 'Mercedes' had been created. | ||

| Karl Ludvigsen | © 2007 autosport.com |

| Send comments to: ludvigsen@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |