Atlas F1 Magazine Writer

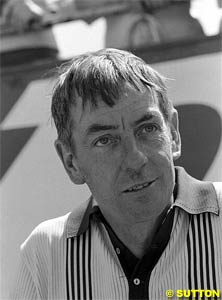

From racing against Jack Brabham to becoming his friend and engineer, from building a car for himself to race to supplying racing machines to teams all over the world with his Ralt company... Ron Tauranac's life has been filled with anecdotes and success. In a candid interview, the now 79-year old Australian tells Atlas F1's Mark Glendenning about his life and much more

Ron Tauranac: Well

I'll have to think about that a little bit. Three or four years, that takes us back

I haven't really been doing much - oh, yes I have, I went to help Phillip Walker out. He has a BT26, I think. So I've been testing with them a few times, and trying to get the car up to date. He runs Walker Freight, and he has a number of historic cars, so I've been helping him out.

MG: Have you enjoyed working with the old Brabhams again?

MG: And you've been working with Honda as well?

Tauranac: I've been a consultant with Honda since about 1979, on and off, when they came to us with their engine in Formula Two. So we ran their engine for a number of years. Then that finished, and I was freelance. In fact, I sold out to March, and I worked for March until they went broke in 1993. And in 93, Honda came to me and they wanted some school cars. So we built three experimental cars which they wanted to try, and they were all 100 percent, so they ordered a dozen cars. So then I got finished (with that) and then I did a little bit for Tom Walkinshaw Racing. They were having trouble with their Yamaha engine, which was really a Judd engine.

MG: This was with Arrows?

Tauranac: Arrows, yeah. I only did a little bit of work there. They were blaming the engine for all sorts of things, but it turned out that they were bailing their oil out of the catch tank throughout the atmosphere, and running out of oil. And they were cracking the number one inlet valve seat, and it was because they had a tie across the heads to transfer the water. And it was stiffer than the chassis and that cracked the head. So we sorted that out.

MG: This didn't happen to coincide with Damon Hill finishing second...

Tauranac:

at Hungaroring. Yeah, that's right - and he was leading that. And then Honda read that I was working (with TWR). I'd stayed in the background, I never said anything. But somewhere or other the press guys working for Arrows (wrote something), and Kawamoto, Honda's CEO, got to hear of it - he was in England at the time, and he read it - and the next morning I got from Japan saying, 'Ron, we don't want you to do this.' I said, 'yeah, but the other bloke's paying me a fortune,' and he said, 'Ron, we don't want you to do this!' He had no authority to offer me anything, and I'd done the job anyway, so with difficulty - Arrows didn't want to let me go - I resigned from them, and just didn't do very much from then on.

MG: Those Honda school cars weren't the last cars that you designed though, were they?

Tauranac: No, while I was just finishing those off, someone came to me for a Formula Renault. Someone in Malaysia wanted half a dozen. The chap that organised it used to work for me. They paid me a deposit, so we designed them and built the prototype, and we were making all the parts for half a dozen and no more money arrived after that. So I ended up inheriting that, so I sold off the one I made and all the bits to

I forget his name

Barry

anyway, he died about two months ago. He was running the car for his son.

MG: So going back to the start, like a lot of people you started out primarily as a driver

Tauranac: Well, I had to build my own car to be able to drive. I had no money, it was just after the war in about '49, and we were driving out - Sunday afternoon drives used to be the fashion then. I heard this noise, and I stopped and looked, and there were cars rushing up and down the aerostrip. And I had a look and I thought, 'well, I wouldn't mind doing that'. Then I managed to run into a chap by the name of Bill Heathrow, and he had a little motorbike workshop down near Central Station (in Sydney). He told me about the 500cc Car Club, so I went and got some Autosport magazines and read about that, and went to Mitchell Library in my lunch hours and read all I could, and

built a car.

MG: So did driving lead to designing, or designing lead to driving?

Tauranac: Well, I built the car, and I tried to study it before it hit (the track). There wasn't very much about it technically, it was hopeless.

MG: It had no shocks the first time you drove it!

Tauranac: I had no shocks, no money

then I learnt that it needed shocks. No I didn't, what I did was stiffen the springs up, and then the next time up at Hawkesbury the wheel rolled under, because there was nothing to limit the travel on the swing-out axles. The eye of the spring broke, the wheel went under and it flipped me again and I landed on top of the barbed wire fence!

MG: For most people, that would be a pretty good incentive to give up driving.

MG: When you started working, it seems that you had a lot of different jobs that gave you skills which inadvertently came in very handy later on.

Tauranac: Yes, that's right. Well, the job I had

well, I did a number of jobs, but the leading one was working for CSR Chemicals. I was in designing - we all designed the factory - and it was jig and tool design where I was more of a specialist. They picked out of 50 draftsmen four of us to supervise the subcontracting of all the stuff. And as it happened, I chose rather than supervising all the welding, to do the casting side of it. So I got involved in castings and pattern making, and then I took the lead in mounted runners and risers on the board, so I knew all about that side of it. So it was a bit of everything. CSR didn't worry about qualifications. If you could do the job, you got it, so you went from one thing to another. Then it was all finished, and I was Shift Supervisor, and I didn't like the shift work so I left and then Frank D Spurway onto me, and I was into designing nuts and bolts and screws and all that sort of stuff. And then Quality Castings - when I was at CSR, they were the people that we subcontracted most of the stainless steel casting to. So they offered me a job as works manager. I went there and met Jack (Brabham) by chance, and used to subcontract work for him, which is how we built up the relationship. He had a little one-man machine shop. I went up there to buy a Velocette motorcycle engine off him, just for my car. We got talking, and I subbed work out, and we got friendly, and then I helped do design work on his car and he did machining for mine.

MG: Did you have any reservations about making the move when he asked to join him in the UK?

Tauranac: That was a big jump. I had a big job, I was works manager, and I had a wife and a four-year-old kid. What had happened was he went to England, and after a few years he went to Cooper and became their works driver. When they were switching from the leaf-spring to the double wishbones he wrote me a letter and asked me what the proportions should be. He fed the proportions in to Owen Maddocks, who was there - he was more of a draftsman than a designer - without Charlie Cooper knowing anything about it. So that's how a lot of the development work happened on that. And he (Brabham) used to come back for the Tasman Series every Christmas and we'd see each other. Then when he was back in 1960, he offered me a return air ticket to go over and see if I liked it for six months. I swapped the return air ticket for one air ticket for me one-way, because I had go via LA to look at a race at Riverside. I helped run his Cooper there in the SportsCar race. And my wife and kid got on the boat and went over. In 1960, that was a hell of a step. I don't know why I didn't think about it more (laughs).

MG: It's probably just as well that you didn't, or you might not have gone through with it.

Tauranac: That's right, yeah. Well, right through life things have happened like that. Like when I sold Brabham out, Colin Chapman got on to me and offered me a job there. I accepted, and he came down in his plane and flew the family up to find a school and a house for the kids, and all that was done. Then on the Monday morning, after we'd spent the weekend up there, he rang up and said, 'can we put it on hold for a little while?' He had to sort something out with his staff, because I think the chap there that had come from BRM wanted the job of top designer. So I just said to Colin, 'well if you can have second thoughts, I can'. And he thought that was a 'no', so we did nothing more until he asked if I could come and race engineer one of his cars at Mosport in Canada, which I did. And then by chance, I hadn't started anything, and then Larry Perkins came and drove up with a car and a trailer in my driveway and asked if I'd have a look at it and see if I could recommend some improvements. I wandered around it and said, 'well, I think it would be easier to start again', and he said, 'well, let's do that!' My wife wanted to get me out of the house, because I'd always worked seven days and five nights and now I was home most of the time, except for a bit of consulting work. She saw a factory advertised and that was the start of Ralt, so all of these things are a little bit by luck.

MG: So there is no regret that things didn't work out with Chapman?

Tauranac: No. Who knows, you never know what the other side of it would have been. But I think it was far better to do my own thing and do Ralt, because that became bigger than Brabham, really. I think at Brabham we made about 550 customer cars, and then at Ralt, over 1000. I think the total of the two was up around 1650.

Tauranac: There are a few things, yeah. I guess one thing that I think mattered from the beginning, particularly after my incidents with the first Ralts, I realised that control of the tyre contact patch was very important. Even if you really didn't know where you ought to make it move, it really had to be rigidly attached to the car, and be very consistent with its movement. So that made it consistent in handling, and gradually I realised that it was important that, because of the varied calibre of mechanics, that you needed to make the car consistent in its set-up. So if you altered, say, the camber, it didn't want to alter the toe-in. And if you altered either one of those, say on the rear suspension, you didn't want to alter the corner weights. Corner weights weren't that important back in the Brabham days. It was only when the cars got much stiffer and the ground effects came in that it became very important. So that's when, in the Ralts, when you designed it you realised you didn't want to screw up the corner weights. Everything was independent adjustment. The other thing I think in the earlier days was where you put the roll centre and the roll centre movement. It needed not to jump around and not to move laterally across the car unless you particularly wanted it to do it. And in doing that, I tried to make the car so that if you liken the handling of a car to a globe, you could be anywhere around the top and it was still going to work alright. Whereas if you made it like an ice-cream cone, you might get much better handling if you're on the peak, and if you fell off the edge because of someone not setting it up right, it didn't handle. So that was my philosophy. Not to make the quickest possible car with Schumacher driving it, but to make something that everyone could drive.

MG: Which is obviously something that you'd have needed to keep at the forefront, given that you were mainly building production racing cars.

Tauranac: That's right, yes.

MG: Do you think your approach might have been different had you focused on designing and building F1 cars? Would your approach have been less

conservative?

Tauranac: I don't know. The Formula One cars seemed to work alright, and there wasn't a problem there, and our Indianapolis car worked fine. That was always built in a big hurry - we didn't know we were going to do it until Christmas, whereas other people started the year before. So we had to rush over there with the car. The first one I did for that, Andretti drove. His mechanic

I think the chap that had the Brabham, crashed it and it needed a repair. And Andretti's mechanic offered to repair it if they could make a copy. So they made two copies, and that became Andretti's car that he won Indy in. And it went on from there.

MG: Your cars were often described as being 'solid and dependable'. I guess this would have been highlighted by the fact that some of the other things that were around, like Lotuses, were renowned for being neither of those things.

Tauranac: Well I think the other difference is that Lotus and all those people employed designers. And the designer had to come up with something new each year, or they won't keep him. And I, if there was a new formula that came out, I sort of thought, 'well, if it lasts four or five years, where's it going to go?' So for a production car one tried to build the car that was going to be right in five years time, you backed off from that and built something that was just good enough to win. And then you keep doing updates. And that meant that cars, particularly like my Formula Atlantics, you could get one three or four years later, and you could still win. The people that had the money would buy the new car to save doing the service. And the people that bought old cars, they were designed as such so that all you had to do was, I'd recommend, put all new rod ends on every year. Again, my rod ends were bigger than everyone else's, because I wasn't saving weight. On all the other cars, like Lotus, they would wear out, and when it got to the slop in it, you'd put another one in. But if it could get some slop in it, you couldn't control your wheel contact patch accurately. So I'd put bigger ones in, they didn't wear, and at the end of the season the fatigue life would set in, maybe, and you'd throw the lot away and get a new lot. So there's a different sort of philosophy.

MG: While reading Mike Lawrence's book (Brabham + Ralt + Honda: The Ron Tauranac Story), I was struck by a remark from someone who once worked with you, who said, 'If Ron could reincarnate, he'd come back as Chapman'. How does that sit with you?

Tauranac: (laughs) No way. See, Chapman had to sing his own praises, and have it done for him by journalists, whom he employed, because he had to get the publicity for his road cars and all the other things. I didn't want any publicity. I just wanted to build the car, and I didn't want anyone copying any ideas. So I never said, 'oh, that's new'. I think Chapman came up with a couple of big innovations - they weren't new. Like, the monocoque had been around twenty years before. He brought that into racing. So there were a few bigger things like that which he made public, like making the engine part of the structure. And BRM had done that anyway, but Chapman got the publicity. But when it comes down to detail, and design innovations and things like that, I think we had, probably, as many as him. We just didn't say anything about them. But I could just list the whole lot. Even simple little things like the driveline.The rubber donuts came in because the plunge in the universal joint was causing the cars to stick up. So they went to rubber donuts, but because of them acting as a U.J. at the pump, they would break. So I put a U.J. on the donut and took the pump out of it, and put the plunge on the donut. Which I think Mercedes did, a year or two later. And there's a whole lot of things, like adjustable anti-rollbars and all sorts of little things. But you didn't say anything, you tried to hide them.

Tauranac: No. They can't, because of the regulations. I would have liked to have gone back when I had nothing on and done another Formula Three car, but you have to homologate a whole lot of the parts in the car for three years. So you've got to homologate it before you can race it. So you can build a car and test it, and you can be testing quicker than the others have done. But unless you are actually at the circuit on the same day and you race one another, you can't tell if you're going to win, because you've got to get out of the corner faster so you can speed down the straight. There are certain little things you can do on your own. But if you're not allowed to change the cars for three years

The other thing is, no-one will probably buy the car, because drivers have got to get sponsorship, and they get the sponsorship from what is known. An unknown coming back in, and trying to get the money to run a Formula Three car

you wouldn't get a top driver. The only way to do it would be to run a top team with Dallaras, build your own car, test against it, when its ready homologate it, and then gradually bring it in because you've already got the sponsorship. And I reckon it would cost nearly a million pounds to get cracking again and do all that.

MG: Lola are well on the way with their new F3 car, though.

Tauranac: Yes, well that was done in Japan, which is a bit different. That was done by

what's the Japanese company that builds

anyway, they've been associated with Honda for a number of years, they've got wind tunnels

they did do a Formula One car, years ago. Anyway they've done a F3000 car, and they've just done this new thing with Lola. Dome. They did all the basic design there, and made most of it, and then Lola had some technical input later on. So it got established in Japan where you don't have all this silly bloody FIA things. Or maybe they did, but they got around it somehow.

MG: There was a Ralt running around in British F3 at the start of the year, too.

Tauranac: Yeah, he's been doing that for about three years. That was one of the two partners that bought out March when it was going bust, Steve Ward. He took the Ralt name, and the other partner took the March name. He's got a farm, and some young guy from Poland wrote to him and said that he wanted to design cars. So he came over and he worked for his board and lodging. He designed the car. The big thing he did different was the gearbox, he had drop gears in it. You keep the weight forward and put the driveshaft up, and he would have gained a bit of horsepower in the days with CV joints. But with tripods, there's virtually no power loss by comparison, so he lost a bit of his advantage. And of course, they haven't got all the facilities with the wind tunnel that Dallara has got built in, and the ongoing thing with about three designers or four designers ongoing. What Dallara did, when Alan Docking was running my cars, Dallara wanted to get him and they loaned him a car and it wasn't quick enough. And Alan Docking, and the manager that he had running it then, let Dallara's two engineers come up and tear the Ralt to pieces, and copy everything they wanted off it. If you look at the wheel bearing set-up and all that, and the hubs, it's a straight-out Ralt. So that got them a bit of a kick-start. They'd been building Dallaras for years, but they got all this into it. I don't know why Alan Docking would do that. He told me afterwards that he did it. In fact, I think when Mike Lawrence was writing the book we happened to be talking with Mike up at the motor show, and we bumped into Alan Docking, and Alan told Mike Lawrence there and then! 'Yeah, I let them come and do that

' I don't know whether Mike put that into the book or not.

MG: How do you see the way the whole designing game has evolved over the past few decades? It has become a lot more specialised since you started out.

Tauranac: Yes, it has. It has become very specialised. People from uni

like, the aerodynamics is the main thing, that's really jumped ahead. Electronics

so there are specialists in each field. There are very few all-round people who can really do (things like) suspension, and marry the whole lot up. I suppose you've got Patrick Head, and John Barnard, and Adrian Newey - although his specialty is aerodynamics. I don't know he how much he has developed in other fields. You've got those sort of people, and there are some others that are reasonably all-round. Most of the older ones. But the younger ones are specialists. OK, it's gone on a long way, but I think there is still room for people that can look at something and make a judgement.

MG: So is this ability to see the car as whole becoming a lost art?

MG: There's less room for innovation, in other words.

Tauranac: That's right.

MG: Do you find it less interesting as a result?

Tauranac: Oh, it's still a challenge, whatever you do. And I think it becomes more of a challenge, to be able to assess what's going on with all these things. You can listen to what the driver's saying, and say, 'oh well, you need to do this or that'. And other people have got to look at the data, and download it, and it takes half an hour

so there's still room for people.

MG: Do you enjoy modern F1?

Tauranac: Oh, I enjoy any challenge. I don't go to it if I'm not involved. I'm not a spectator. I've got to be doing something, and if I watch it on the box I tend to go to sleep after a while. I used to rely on Murray Walker to scream, and he'd wake me up and I'd see the replay.

MG: Do you have a particular affection for any of the cars that you have designed?

Tauranac: Not really. I suppose the best of the Formula Three cars was the RT35. It went on and on being best even after it was outdated by composites and all that. It was a honeycomb car, and it worked. And I suppose the

I forget all the numbers, but in the Brabham days, the 30 was pretty good. That was the first aluminum monocoque that we'd done in - we'd done an aluminum monocoque at Indy before that, but you didn't need it for Formula One. You didn't need a particularly stiff car then, because you didn't have stiff springs, and you were able to get the body shape to get the air out. It was only when they brought in that you had to have bag tanks that it became desirable to do a monocoque and put the bag in the monocoque. Well, it was compulsory. That turned it around, then.

MG: Did you ever see a car that you wished you'd designed?

Tauranac: There was an article about that in Motor Sport magazine. I did an article for them. Most of the ones I would have done were gone by then. I think probably the Lotus 76, the one that had the first ground effects? The following year, the Williams did a much better job, because Chapman decided to carry the design philosophy right through to the back of the car and made it all too complicated. But that was a jump forward

by accident, as most things do.

Mark Glendenning: Could you start by bringing me up to date with what you have been doing over the past three or four years?

Tauranac: Oh, it doesn't really matter. A car's a car, and I don't really remember anything specific about them all. You can recognize your own handiwork, what you've done. And of course, my wife died two years ago, so I've had to sell all the family goods and the house. I've mainly been getting organise to sell the house. Of course, I go skiing for the winter every year.

Tauranac: Oh, it doesn't really matter. A car's a car, and I don't really remember anything specific about them all. You can recognize your own handiwork, what you've done. And of course, my wife died two years ago, so I've had to sell all the family goods and the house. I've mainly been getting organise to sell the house. Of course, I go skiing for the winter every year.

Tauranac: Well no, I carried on after that. I went alright after that. I then eventually found some money for some dampers, and realised that you had to limit the travel on the swinging halves, and then started designing a better geometry for the swinging halves. Instead of having the short swinging halves, I made a triangulation that crossed over, so that the half axle was in fact three-quarters of the width of the track - which Mercedes did a year later on their Sports Car. They didn't see my design, of course, but it came out on that car a year later.

Tauranac: Well no, I carried on after that. I went alright after that. I then eventually found some money for some dampers, and realised that you had to limit the travel on the swinging halves, and then started designing a better geometry for the swinging halves. Instead of having the short swinging halves, I made a triangulation that crossed over, so that the half axle was in fact three-quarters of the width of the track - which Mercedes did a year later on their Sports Car. They didn't see my design, of course, but it came out on that car a year later.

MG: Is there a common characteristic or concept across your cars?

MG: Is there a common characteristic or concept across your cars?

MG: Ralt's modern equivalent would be Dallara. Do you see anybody breaking its monopoly in F3?

MG: Ralt's modern equivalent would be Dallara. Do you see anybody breaking its monopoly in F3?

Tauranac: A little bit because of that, and another bit because of the FIA regulations. With all these one-make formulae, there is just nowhere to go for all these young designers. If they got in and they were able to develop the car, it's like the problem with Formula Three - you homologate it, and you're stuffed. So out here, they have year-old models or older for their series, but you can't do enough to train people.

Tauranac: A little bit because of that, and another bit because of the FIA regulations. With all these one-make formulae, there is just nowhere to go for all these young designers. If they got in and they were able to develop the car, it's like the problem with Formula Three - you homologate it, and you're stuffed. So out here, they have year-old models or older for their series, but you can't do enough to train people.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 3

Articles

A Farewell to Arms?

Technical Analysis: Toyota TF104

Technical Analysis: Jaguar R5

Interview with Ron Tauranac

2004 Countdown: Facts & Stats

Columns

The Fuel Stop

The F1 Trivia Quiz

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |