Atlas F1 GP Editor

What moves a man to buy a struggling and uncompetitive Formula One team on the verge of disappearing? The answer is passion, and Paul Stoddart has a lot of that. Say what you will about the Australian businessman, but since taking over the Minardi team, both he and his staff have been keeping the Anglo-Italian squad alive and kicking. David Cameron spent the Japanese Grand Prix with Stoddart and his colleagues, visited their Faenza factory, and heard from them about the struggles and joys of running the poorest team of the field. Exclusive for Atlas F1

And at the end of 2000 that was about as bad as it could get.

"I think it's fair to say Minardi was finished," Stoddart grimly recalled of his leap of faith from the relative safety, typhoons notwithstanding, of his office behind the Japanese pits on the final race weekend of yet another long year for the team. "They had no engine, they had six weeks and three days before the start of the Melbourne Grand Prix, and when I first arrived in the factory there was a reduced workforce of very loyal but totally demotivated people who were all convinced that the door was going to close. There was a wooden mock up (of the chassis) with the wrong engine bolted up to it. It was a pretty daunting task.

"The fact that I remember it was six weeks and three days is because I probably remember every single day of it, but having said that we did what people said could not, and would not, be done. Nobody gave us any chance of arriving in Melbourne, and it was close (Fernando) Alonso's car arrived there having done one 150km shakedown, and poor old Tarso (Marques)'s car we actually bolted together in the pitlane in Melbourne, and it had never even turned a wheel until Friday running! I don't ever want to go through that again, but I think it's probably fair to say that Minardi wouldn't have survived to the end of 2000 if I hadn't come along."

Undoubtedly Stoddart saved the team from oblivion, and spent the next few years constantly dipping into his own pocket to make sure they stayed on track. Although he arrived too late to enjoy the team beating BAR in their debut year (although undoubtedly it put a wry smile on his face), he has been able to help Minardi beat famous racing names like Prost, Jordan, Arrows and Jaguar on occasion over the ensuing years, despite having a fraction of their budget (as well as managing to outlive all bar one of them, so far). And yet the only recognition some fans give these achievements is to state "the bloody Minardi's are getting in the way" when their red compatriots shape up to lap the men in black on race day, without once considering that their sheer existence is more than a little miraculous.

Minardi wouldn't exist now if it hadn't been for Stoddart's wallet and, despite the quiet affection most aficionados have for the outfit, the team principal seems to get no respect for this. On the other side of that coin, were it any other team that he found in such a mortally wounded state, the results would have been terminal; when you've skated on thin financial ice as often as Minardi have you learn to tread lightly. Racing is the pheromone that floats in the air in Minardi's home town of Faenza, one that the locals breathe deep; it would take more than having no money to stop them doing what they live for, what they love.

"Minardi is a group of people with a real passion for the sport, a real love of cars and Formula One obviously, and let's say a proper team one hundred people where everybody knows each other and if I finish my job I can help someone else because it helps, and at the end of day it's nice to have a beer together, so why not? If I help you now you will help me next time, and I know that this doesn't happen in all the teams - when a team is very big it is very difficult to manage, because people will do just what they are told to do, nothing else - but here it's very different."

Minardi are the tenth best motor racing team in the world, and closing in on number nine they just have the misfortune of racing solely against the nine that are bigger, better. If you put Minardi up against the brightest and best from the IRL, Le Mans, CART, Nascar or any other championship you could care to mention the Italians would make them hurt. The level of facilities they have is, if not second to none, then at least tenth.

"Yeah, it's all there," Stoddart smiled. "When I came to Minardi one of the biggest things I changed was that they were making about thirty five percent of the cars in house and subcontracting the rest out we increased that rapidly to about seventy percent, and it's probably edging towards eighty percent of the car now made in house at the factory. Our carbon shop is fantastic, and our machining and fabrication shops are adequate; you don't see all the new million dollar machines, but the ones that are there do a perfectly good job, and of course the strongest thing any team has is its workforce."

Renault have five stereo lithography machines available the machine that allows CAD designed parts to be downloaded directly from the designer's computer and built, layer upon layer, by a laser etching the rising resin level, with the resultant piece to be utilised in wind tunnel tests Minardi have just one, along with a similar machine which carves foam blocks into computer designed shapes to aid with carbon composition. Renault build seven racing tubs a year, Ferrari build nine, while Minardi has to make do with just four. The big teams have almost unlimited use of autoclaves, the industrial machines used in bonding the various layers of carbon fibre together for the car's bodywork Ferrari even have a portable autoclave available at most European races Minardi have just three autoclaves, small, medium and large, and a usage roster.

Renault have all of their car manufacturing facilities on one site in Enstone, and it's an impressive sight to take in. You drive through the surrounding countryside and along a lengthy gravel driveway, far from prying eyes. Walk through the front door, past the half size model of the latest car, and the white collar work is all done behind the receptionist public relations, accounting and marketing to the right, or turn left and you pass Flavio Briatore's grand office on the way to the large, open plan designers room, which has around fifty designers at a time working on their individual projects in one of two shifts a day, surrounded by the offices of the various section heads. Downstairs is the blue collar work, the machines that cut and mold and press and bond, all revolving around three bays with the latest race and test cars are set up and ready to roll, all on a floor so spotless you could eat off it if you were so inclined. The wind tunnel is just through the doors and across a lane, removed from the building so as not to disturb the occupants, with their colour coded resin models awaiting the penultimate test. The entire compound is focused on the chassis only the engine is designed and built in Viry Chatillon, France.

Minardi's factory isn't quite so grand. In the middle of an anonymous Italian industrial site and across the road from a poultry factory and a brewer, the office would be easy to mistake for a warehouse but for the team's newish logo on one of the pre-fabricated walls. In the reception there is a coffee table with the old logo and colours prominently displayed, along with a collection of trophies and mementos lining the stairwell from the team's pre-Formula One days Minardi had a tremendous record in the junior categories as well as other classes of racing, including a truck once built for the Paris/Dakar race. They were, and are, a racing team, in all that that entails.

Downstairs the three chassis are in their racing pit set-up the same rig that the team use at tracks around the world is also used back at the factory and flowing wide around them are storage areas for the various spare components, the bits and pieces that form the cars. Directly below the design room are the computer aided casting machines whirring away, fabricating yet more parts. The team outgrew the building that has been their sole home a couple of years ago, taking over the lease of the other two buildings on their side of the block to house two of the autoclaves as well as the carbon fibre department and various other design areas. The floors in these buildings, while clean, are tiledfunctional, but in stark contrast to the sterile facilities of their competitors.

Minardi don't have a wind tunnel of their own the outlay to have one designed and built is currently beyond them. They make use of Lola's facilities as and when they need to, presumably at a discount provided by current boss Rupert Mainwaring, the former sponsorship hunter for Minardi. Former employees of the team tend to stay on good terms even after they leave, although not that many of them actually do go.

Of course, every racing team works hard; every racing team is there to compete against each other with the aim to beat the others. The teams in Formula One have moved so far ahead of every other series due to the advances made in testing and manufacturing equipment at their disposal, and the reason that these advances came into existence is the vast sums of money thrown at the sport in the last decade. In the 1996 season, Ferrari, who had been struggling for some time and had just brought the two-time World Champion Michael Schumacher onboard with the aim of turning the underachievement around, were alleged to have a budget of $100 million for the year in 2004, reports put their budget at four times that figure.

Formula One seems to have ignored the worldwide economic downturn of the last few years in the hope that it will go away, and certainly a number of the larger teams have come up with budgets that defy logic. "I think a lot of people were looking at Formula One at the end of the nineties and saw it as an incredibly valuable franchise business that was a sport first and a business second," Stoddart noted grimly, "but unfortunately post 9/11 and post the year that I took over a lot changed in the world, and a lot changed in Formula One. Unfortunately we went into a recession, we had the horrific events of 9/11, and it rapidly became a business first and a sport second, which is quite sad.

"There's been a lot of goings on over the last four years that have made the off-track action sometimes more interesting from a public point of view than the on-track action, which is quite sad. Minardi obviously had its best season with me in 2002 when I think everyone in Australia felt that we had won the Australian Grand Prix, and we also finished ahead of a works team that had a budget that was probably some forty times our budget, which is one of the things that you can be proud of at Minardi.

"But I think not only are we one of ten teams at the pinnacle of motor sport in Formula One, but also I'm very proud of our job with the drivers, because a lot of the value that people don't see in the small teams, the Jordans and the Minardis, is the drivers we bring through we had a record at one of the Grands Prix last year where eight of the twenty drivers were Minardi drivers past or present. Those are the kinds of statistics that speak for themselves, and it's the true value of the small teams it's not just the drivers, it's also the engineers, the mechanics, etc. that all come through the ranks they've all got to start somewhere, and Minardi give them a chance to start.

"In plain commercial salesman speak you get more for your dollar (with us), so if the entry point is x with Ferrari and it's y with Minardi, and it's not a criteria that you're at the front and with a winning team, then one would suggest you can get a lot more for your dollar with Minardi. If you had a product that was being launched and you wanted some international, pan-European exposure, and were building your programme around Formula One and not necessarily a team, then I'm sure we could deliver a good return for them. It's still difficult finding those companies, but moneywise this year we've had the best year Paul's had in terms of getting the revenue in, so maybe we're doing something right.

"I also think that if you look back historically Minardi has introduced some key sponsors Telefonica and Mild Seven are two that I can think of immediately and a sponsor needs to be educated as well as drivers do, as well as everybody else. There's an argument that we could be seen as an academy as such, although we haven't been as successful as we have been in the past!"

The cars are so close to each other now, are so similar given the fixed dimensions laid out in the sporting regulations and similarities in measuring and design tools, that the differences come down to money, and who can spend it in the best manner towards a common goal of having the fastest car. It's a race that Minardi have no hope of winning on the track conditions could contrive to help them to a good result (Stoddart still continues to believe that Jos Verstappen would, at the very least, have brought home a podium finish if he had stayed on the track in last year's chaotic Brazilian Grand Prix, for example), but money never falls from the sky no matter how much you might wish for it.

"I know exactly where I'd spend it we'd be incredibly thrifty with what we do because we know the areas that need money, particularly aero and wind tunnel time. We know the improvements we would make, and we know how much it would cost to do it. The reality is we would only beef up certain areas of personnel most of the money would be spent on the car, and on certain aspects of the car that are currently starved for money when you have a small budget.

"The facilities by Formula One standards are without doubt the least in the Formula One grid Minardi is the only team that doesn't have its own wind tunnel, we hire one and Minardi is the smallest in terms of numbers of personnel at about 114, and in facilities, but we also have the facilities in the UK, and if you put the two together then it starts to look a bit more sensible. And the facilities in the UK are already producing the Minardi two-seater engine, and did produce the 2001 engine, so if we had to we could produce the engine in the UK next year. But it works."

So maybe it is strange to be Paul Stoddart, but he doesn't seem to be complaining too much; he's taken a lot of hits in his time in Formula One, but mostly he rolls with the punches and keeps coming back up. Sure, he knows that without the budgets enjoyed at the other end of the pitlane he's unlikely to move up the grid, but at this stage still being in the show is a success in itself. And if the money comes, he's got a plan in place to make things a little easier, to make the cars a little faster, to let the team compete a little more successfully.

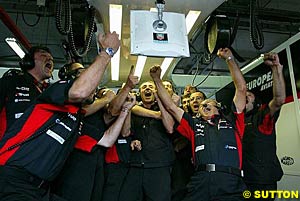

And mostly he knows that, should it come together, the team will make the most of any chance that comes their way. "The fact is that Minardi is just full of passion, the people love to come to work, that's a difference,

"And every now and again we have one."

In the garage they move like a well oiled dance troop, choreographed to perfection; one mechanic puts on the new OzJet stickers as the tyre mechanics roll on around him. Gimmi Bruni has his helmet waiting for him on a cooling fan as he arrives; he lifts it and puts it on as one mechanic removes the fan, switching it off and hanging it above the third car as another one removes the rolls of tape it was sitting on and clears them away.

As the start of the practice session approaches everyone moves as one; everything has to be done at once, and they make sure that it is. They carry the large starter motors with a practiced surety around the onlookers at the rear of the garage, sliding them home with a clunk into the back of each car, and the ground vibrates when the engines start, the air rich with sweet, orangey smelling fuel as you feel the wind of the exhaust. The cars roll out, one after another into the sodden gloom outside; the mechanics clean the floor and get ready for their return.

The tyre warmers are in hand as they roll the car back in, the stinking smell of hot brakes and rubber filling the air as they do; smoke filters from within the rims as they put the tyre warmers back on the steaming rubber. Everything is plugged back into the overhead rig; the bodywork is taken off and wiped dry before being returned to its rightful place.

They check everything all the time tyres, engines, components the grey hairs in the middle around Bas Leinders, watching the younger men around the other drivers. Race engineers talk constantly to their drivers, starter motors constantly attached to the cars, just in case. And then they wait for the weather.

Bruni sits in his car and talks animatedly to his race engineer about something, who then speaks calmly into his mouthpiece before two mechanics bring out a new rear wing from behind the pit. The wing is changed in under a minute, the old one put out the back with the other spares, along side the unused engines and suspension units in a room that doubles as host to the telemetry computers; cramp but functional. Every other piece of space is filled with tyres, in and out of their warmers.

Two days later, before the start of the race, they go through the same process again until their duties are discharged with a roar of an engine that you can feel in your guts. After the cars have left, the mechanics stare at the pitlane; they can't see the track, but they keep staring anyway, nervous tics to the fore; one constantly flicking his nose with his pen, another tapping the workbench with his fingers.

They swear a lot they're mechanics, they're racers it's a bleeder valve for emotions set on high. They touch each other constantly as though for reassurance, all hands and movement, bumping into and excusing themselves continually. They bump into each other now, it seems, so that they won't do it when it counts.

Pitstops from inside the garage are an explosion of noise and movement. They take no time at all, seemingly less than when you are watching the action on television from home or even from the media centre, and all you can see is a blur of black and red from the noise producing machine in front of you, sat squat with violence. It makes your heart race just standing there it's a mystery how they all get out of the way in time, of their own car or the others sliding past in the pitlane.

But they do, and they grin broadly as they move back inside, back to where the action is on television rather than in their own hands. And they wait for another chance to come around, another chance to get it right again.

It must be strange to be Paul Stoddart. Starting from scratch he built up an airline out of a bunch of promises and an unlikely deal with the Australian Air Force, made a bit of money and then became in effect the ultimate Formula One fan of his time when he bought the remains of the Tyrrell organisation after the embryonic BAR stripped out the rights to compete in the series and little else, putting Uncle Ken out to pasture and turning off the lights in the factory as they left. Which meant that he had the ever aging equipment, without the ability to actually use it to go racing.

Not long afterwards he was sitting in his new facility in Ledbury when he read that Minardi, the underfunded but much beloved team built on a dream and little else by third generation racer Gian Carlo Minardi, was about to pay the ultimate price for the past few years of financial mismanagement by their owner, Fondmetal's Gabriele Rumi. Sensing a way into Formula One Stoddart swooped, and against no competition at all he made the deal. The good news was he was now in Formula One the bad news was it was with Minardi.

Not long afterwards he was sitting in his new facility in Ledbury when he read that Minardi, the underfunded but much beloved team built on a dream and little else by third generation racer Gian Carlo Minardi, was about to pay the ultimate price for the past few years of financial mismanagement by their owner, Fondmetal's Gabriele Rumi. Sensing a way into Formula One Stoddart swooped, and against no competition at all he made the deal. The good news was he was now in Formula One the bad news was it was with Minardi.

Massimo Rivola, Team Manager (seven years at Minardi): "We have the most challenging job in the paddock - I'm not joking! It's something that makes everybody in the team proud, and if you consider the budget and the number of people employed you can really see what we are able to do. We used to say never give up, and we saw those other teams disappear from the grid, so it's really something that is like a very good gym - you train and feel ready to do something, anything, and we are. We have very few people to do the tests and the cars and the marketing and the logistics and everything, and obviously it's very difficult for the people outside; they cannot understand our efforts to survive, so they can't understand why we are slower than the top teams; but we know exactly why. I can't say exactly what would happen if we had the other teams' budgets, but I can say for sure that if the other teams had our budget they would not be able to stay alive!

Massimo Rivola, Team Manager (seven years at Minardi): "We have the most challenging job in the paddock - I'm not joking! It's something that makes everybody in the team proud, and if you consider the budget and the number of people employed you can really see what we are able to do. We used to say never give up, and we saw those other teams disappear from the grid, so it's really something that is like a very good gym - you train and feel ready to do something, anything, and we are. We have very few people to do the tests and the cars and the marketing and the logistics and everything, and obviously it's very difficult for the people outside; they cannot understand our efforts to survive, so they can't understand why we are slower than the top teams; but we know exactly why. I can't say exactly what would happen if we had the other teams' budgets, but I can say for sure that if the other teams had our budget they would not be able to stay alive!

Fabiana Valenti, Press and Accounting Departments (five years at Minardi): "You know, this is my first experience in Formula One, and I can't compare the job in Minardi with a job in any other team, but I am quite sure that the job in Minardi is much better than anywhere else, at least for me. I am very proud to work with Minardi, and if I had the chance to go somewhere else I wouldn't go, actually, because this is a family everybody's got a nickname, everybody's got the possibility to improve professionally because everybody has to be able to do more than one job. The energy is always so much, you can feel the passion - you can breathe it. I am quite sure this is not just a job for the people who work in Minardi."

Take a tour of the Minardi factory on a crisp autumn day and you begin to see Stoddart's point. While the facilities are light years away from the grand structures of Ferrari, McLaren or Renault, almost everything that you could need to design and build contemporary Formula One cars can be found on site, albeit in smaller numbers than the big teams.

Take a tour of the Minardi factory on a crisp autumn day and you begin to see Stoddart's point. While the facilities are light years away from the grand structures of Ferrari, McLaren or Renault, almost everything that you could need to design and build contemporary Formula One cars can be found on site, albeit in smaller numbers than the big teams.

Up those stairs you will find a small corridor lined by offices, but the lines of demarcation aren't clearly defined in a team the size of Minardi, everyone does at least two jobs (there are only 114 employees, whereas Ferrari is well past a thousand) press and marketing and accounts are all jumbled together and lit by desk lamps fabricated from used brake discs, with one end of the corridor leading to the design room, a collection of ten or twelve desks with their occupants peering up in surprise at seeing a visitor rather than a team member, the other end remaining as ever the office of once owner, now Muse, Gian Carlo Minardi. If he is in the factory when a guest comes to visit, he asks that they come and say hello at the end of the tour.

Up those stairs you will find a small corridor lined by offices, but the lines of demarcation aren't clearly defined in a team the size of Minardi, everyone does at least two jobs (there are only 114 employees, whereas Ferrari is well past a thousand) press and marketing and accounts are all jumbled together and lit by desk lamps fabricated from used brake discs, with one end of the corridor leading to the design room, a collection of ten or twelve desks with their occupants peering up in surprise at seeing a visitor rather than a team member, the other end remaining as ever the office of once owner, now Muse, Gian Carlo Minardi. If he is in the factory when a guest comes to visit, he asks that they come and say hello at the end of the tour.

Andrew Tilley, Chief Engineer (three years at Minardi): "The good thing about Minardi, I suppose, is it's a small team so everyone works together very well, and people are very much involved with all aspects of the work it's not as departmentalised as the big teams. A lot of that is necessity we have eighty or so people and everyone has to pull together, and when we come to the races the factory is pretty much empty. Obviously that makes it very difficult, because everyone has to work very hard, and it's difficult to achieve a good result with the small resources we have relative to other people. Everyone wants to help the team survive I worked here getting on for ten years ago, I was close to the people I worked with at the time, and a lot of those people are still here - I sort of felt that I owed them a favour when I came back (Tilley worked as Race Engineer for Jean Alesi at Sauber, as well as holding positions at Lotus, Benetton and Jordan) three years ago. And I'm still here.

"(Minardi's strength) is the ability to achieve what we do with a very small resource if you look at the budget we have available, the number of people we have available, I think we do a very reasonable job we are snapping at the heels of Jordan most weekends and they have a more competitive engine, more resources, their own wind tunnel, and a lot more people. So the strengths are in the quality of the people we have, and the way that everyone works together, and works hard."

"(Minardi's strength) is the ability to achieve what we do with a very small resource if you look at the budget we have available, the number of people we have available, I think we do a very reasonable job we are snapping at the heels of Jordan most weekends and they have a more competitive engine, more resources, their own wind tunnel, and a lot more people. So the strengths are in the quality of the people we have, and the way that everyone works together, and works hard."

"Of course we'd like to be further up the grid, but unfortunately in today's mega league of budgets it's a bit of a Catch 22 to get more sponsorship in order to be faster you need results, and to get those results you need the sponsorship, so it's a Catch 22 situation. But having said that we keep trying, and Minardi is now the fourth longest surviving team in Formula One, after only Ferrari, McLaren and Williams in that order, and that's something to be pretty proud of. We look for the day that finally the commercial agreements are sorted out, and that'll probably be at the end of 2007; at some point we'll be able to give ourselves a decent budget and go out and see what the potential of all these dedicated people really are, which is something more than we're seeing at the moment."

"Of course we'd like to be further up the grid, but unfortunately in today's mega league of budgets it's a bit of a Catch 22 to get more sponsorship in order to be faster you need results, and to get those results you need the sponsorship, so it's a Catch 22 situation. But having said that we keep trying, and Minardi is now the fourth longest surviving team in Formula One, after only Ferrari, McLaren and Williams in that order, and that's something to be pretty proud of. We look for the day that finally the commercial agreements are sorted out, and that'll probably be at the end of 2007; at some point we'll be able to give ourselves a decent budget and go out and see what the potential of all these dedicated people really are, which is something more than we're seeing at the moment."

Paul Jordan, Commercial Director (two years at Minardi): "I've had the fortune or misfortune to work for the bigger teams, the BARs and the Benettons and the Jordans, and I think corporate politics can sometimes get in the way of racing as we have seen, and are probably experiencing at the moment. That's only a personal view, and I think I fit better to a more entrepreneurial led organisation, which I had with Eddie [Jordan] and I now have with Paul. But it's tough - it's almost impossible to secure additional sponsorship, but we do, and we seem to continue to do that.

"In terms of what other people have in budgets we're achieving probably 97% on less than 10% of the budget," Stoddart smiled ruefully, "so someone's got it wrong somewhere. People will say 'yeah, but you're last so therefore you've got it wrong' probably somewhere in the middle is the truth we don't always want to be last, we're just locked into that at the moment because of the budgets and the way the distribution of wealth in Formula One is so geared to the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, but one day there'll be a change to that, and it will probably be at the end of 2007. It'll always be easier for a team like Minardi who, if they get a bit more budget, can spend it wisely and show some serious performance increase. It's much harder if you've been used to having $400 million and someone takes $100 million away - that's where you struggle. So I long for the day when we have another $20 million to spend it sensibly, and someone else has a cut of maybe fifty or a hundred million to bring them back to some kind of a reality check.

"In terms of what other people have in budgets we're achieving probably 97% on less than 10% of the budget," Stoddart smiled ruefully, "so someone's got it wrong somewhere. People will say 'yeah, but you're last so therefore you've got it wrong' probably somewhere in the middle is the truth we don't always want to be last, we're just locked into that at the moment because of the budgets and the way the distribution of wealth in Formula One is so geared to the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, but one day there'll be a change to that, and it will probably be at the end of 2007. It'll always be easier for a team like Minardi who, if they get a bit more budget, can spend it wisely and show some serious performance increase. It's much harder if you've been used to having $400 million and someone takes $100 million away - that's where you struggle. So I long for the day when we have another $20 million to spend it sensibly, and someone else has a cut of maybe fifty or a hundred million to bring them back to some kind of a reality check.

and at the end of the day we're incredibly proud of our driver record and what we've done over the years. With over 300 Grands Prix, we're the fourth oldest team in Formula One, and also without question we are still the people's team if you ask people what is your second favourite team they will say Minardi, because we're the team that everybody would like to see have a good day.

and at the end of the day we're incredibly proud of our driver record and what we've done over the years. With over 300 Grands Prix, we're the fourth oldest team in Formula One, and also without question we are still the people's team if you ask people what is your second favourite team they will say Minardi, because we're the team that everybody would like to see have a good day.

Sidebar: The View from the Garage

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 50

The Survivors: 20 Years of Minardi

Interview with Gian Carlo Minardi

The Passion of Stoddart

Making Something out of Nothing

The Minardi Factory Tour

Minardi's Cars Through the Lens

Minardi's Drivers Trading Cards

The Minardi Trivia Quiz

Regular Columns

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |