Backward glances at Fangio and Fittipaldi

Atlas F1 Columnist

The Japanese Grand Prix will make history one way or another - if Michael Schumacher clinches the World Championship, he will surpass all before him with a record sixth title. If Kimi Raikkonen beats the German, however, the Finn will become the youngest Champion ever. Either way, one record will be broken, and either Juan Manuel Fangio or Emerson Fittipaldi will move a line down in the record tables. Before that happens, Don Capps pays tribute to Fangio and Fittipaldi - and tells the story of how they each managed to obtain their place in the record books

Juan Fangio did not begin his driving career until 25 October 1936. Considering that he was born on 24 June 1911, in Balcarce, Argentina, this makes him over 25 years old before running a single race in any category. His passion prior to this was football - soccer. Known as el Chueco, or the "bandy-legged one" for his gaucho-like gait on the pitch, was an excellent and skilled player. That he was also adept at keeping the team transportation running was a bonus to the Balcarce team.

Entering a race on the Benito Juarez circuit on that date in a Ford Model A taxi (!), and using the name "Rivadavia," Fangio retired from his first race when a bearing seized due to an oil leak. For Fangio, however, that was unimportant. What mattered was that he found that he enjoyed racing cars. Soon this enjoyment would lead to his competing in the great form of South American motor racing that has now ceased to exist - the great long distance races that literally spanned the continent. The distances were not measured in mere thousands of kilometers, but thousands of miles.

Two years after his first racing event, Fangio competed in his first great racing events, the Gran Premio Argentino de Carreteras, running in two that year. In 1939, Fangio gained recognition as a rising star when he drove a Chevrolet against the Fords in the Gran Premio and gave them a true run for their money. At this point in history, the only thing vaguely "racy" about a Chevrolet was its name. In 1940, Fangio won a grueling Gran Premio that ran from Buenos Aires to Lima - and back again, which meant crossing the Andes twice. The race distance was 5,868 miles.

Running from 27 September until 12 October, Fangio fought fatigue, altitude sickness, and the usual mechanical mayhem racing at speeds far above what the roads - a loose terms in many cases - were meant to be driven. By dint of sheer will and determination, Fangio won the race, a Chevrolet besting the stiff competition of the Fords and especially those of the Galvez brothers. In later years, it would be this race that he would name as his most satisfying victory.

In 1948, he had one of the few crashes of his career. Competing in the Buenos Aires-Caracas Gran Premio, Fangio in his Chevrolet and Oscar Galvez in his Ford were dicing for position when they touched. The Chevrolet barreled off the road, crashing. Fangio's riding mechanic, Daniel Urrutia, died of his injuries. Fangio called this the low point of his career.

In 1948, Fangio was finally offered a drive in a Grand Prix car, one of two 1.5-litre supercharged Maseratis imported by the Argentine Automobile Club for the use by Argentine drivers in the new Temporada series. He drove the Maserati in the first two to of the four events comprising the series. The car was simply not capable of allowing Fangio to challenge the visiting Europeans. Offered a Simca-Gordini to drive in the last two events, Fangio wrung the maximum out of the lighter, more nimble machine. At Rosario, Fangio and the great Jean-Pierre Wimille - also at the wheel of a Simca-Gordini, fought a battle almost to the end, Fangio leading Wimille at several points until the European pushed past to take the win.

The next year, the Argentine club imported some racing machinery more competitive for its drivers in the Temporada, two Maserati 4CLT/48, one for Oscar Galvez and the other for Fangio. Each won an event, Fangio winning the final event of the series, at Mar del Plata. With the success of Galvez and Fangio, the Argentine auto club decided to field a team in Europe. Fangio accepted an invitation to race as a member of the team, something he planned to do for a single season and then return to his business of selling trucks. After all, he was 38 years old.

In 1948, Fangio had been part of a reconnaissance that the club had taken in view of how to place Argentine drivers into the sport of motor racing. The group toured not only Europe, but the United States as well, taking in the Indianapolis 500 prior to sailing for France. At Monte Carlo and San Remo, Argentine Clemar Bucci raced a Simca-Gordini. Fate tipped its hand when Maurice Trintignant was injured and Amedee Gordini needed a racing driver. Fangio simply knocked on Gordini's door and asked for the ride - and got it. Although the Gordini was scarcely the ideal mount for Reims, Fangio placed the little Gordini in the middle of the front in the preliminary event, the Coupe des Petites Cylindrees, and was running fourth when a leaking fuel tank forced him to retire.

The hole in the fuel tank was repaired in time for the Grand Prix. Fangio managed to tuck the little Gordini into the slipstream of the Lago-Talbots who were in turn trailing the cars of the Alfa Romeo team. Fangio stayed with the larger Lago-Talbots until the engine in the Gordini cried, "Enough!" and expired. Fangio was now determined to come back for another shot at Grand Prix racing.

The first event on the Argentine club's schedule was the race at San Remo, an event run through the streets of the town. In practice, Fangio was second to Prince Bira on Friday and took the pole on Saturday. However, the Maserati 4CLT/48 lost oil pressure and ran a main bearing. Fangio himself repaired the damage prior to turning in that night. Fangio won both of the heats, Prince Bira finishing second and establishing the fastest lap of the race. This was to the first of many Grand Prix victories for Juan Fangio.

In 1950, Fangio drove for the Alfa Romeo team along side Nino Farina and Luigi Fagioli, as well as several guest drivers. He won at Spa-Francorchamps and Reims-Gueux and finished second to Farina in the inaugural World Drivers' Championship established by the Commission Sportive Internationale (CSI) of the Federation Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). In 1951, he would win the championship after a season-long battle with Alberto Ascari of Scuderia Ferrari.

On the second lap of the first heat of the Gran Premio dell'Autodromo di Monza on 8 June 1952, Fangio brushed the low barrier inside the second Lesmo. Fatigued after dashing from racing the V-16 BRM in Northern Ireland on Saturday to Monza on Sunday afternoon - driving from Paris after being left by Prince Bira who had offered to fly Fangio to Monza in his private plane, getting flights to London and Paris, and then finding all the flights canceled by weather out of Paris and then Lyon, finally borrowing the Renault of Louis Rosier to complete the trip to Milano - Fangio reacted just a split second too late to the developing slide. Having charged from the rear of the grid in a car - the Maserati A6GCM/52 - he had never sat in prior to the race, to seventh on the first lap, the slide turned into a skid and the Maserati hit a haybale sitting at the side of the road, and then the bank at the edge of the track. The impact upended the Maserati and tossed Fangio from the car. He recalled losing the car, striking the bank, the car turning over as it sailed through the air, the approach of the trees, then being tossed out of the cockpit. Fangio had the good fortune to land on a relatively soft patch of grass. And then passing out.

Fangio severely damaged his spine in addition to a concussion - the latter lessened by the newly required crash helmet he was wearing - and wound up in a body cast for the better part of three months. There were real doubts that he would survive and even more that he would not return to racing after such severe injuries. Fortunately, that would not prove to be the case. By the end of 1952, Fangio was back in a car and back to par.

Unfortunately, the Alfa Romeo service pits in Bologna lacked any welding gear to repair the chassis. So, Fangio set off in pursuit of the Marzotto Ferrari. Using only the gears to brake the car and having to take great care in lining up for the bridges along the route, Fangio still averaged over 100 mph for the final section - which wound through the mountains, and despite all the time lost, still managed to finish second. A remarkable effort.

In 1954 and in 1955 and in 1956 and in 1957, Juan Fangio emerged as the CSI World Drivers' Champion. With his title from 1951, that made five championships for Fangio. He won 24 of the 51 championship events he entered. He also won a number of other Grand Prix events not included in the championship. He was active in the sports car races as well, winning the Swedish Grand Prix and the Sebring 12 Hours among others.

Most importantly, he was a gentleman. He retired in 1958, after bringing home his Maserati in fourth position. Although he considered competing at Indianapolis that year and perhaps a few other events, at the age of 47 Fangio returned to Argentina and a retirement that was iffy after the Peron regime was overthrown. Fortunately for Fangio, his politics were essentially not an issue and he settled into a long, fruitful life. His death on 17 July 1995, was truly the end of an era. He was gentleman and a great ambassador of the sport of motor racing. Most importantly, however, Juan Fangio, a man who often stopped to greet the mild and meek of the racing world, the young boys who knew a true champion when they saw one. I almost went a whole day without washing my hand the first time Fangio shook it. When it once again shook that same hand years later, the eyes were exactly the same as they had been the first time: friendly and warm, not what one would necessarily expect. And once again, I avoided washing that hand as long as I could...

The motor in the ultralight failed at an altitude of 300 feet over a swamp on the farm. The aircraft stalled and then crashed into the swamp, the impact being lessened by the water and soft ground. Fittipaldi and his son were not rescued until their disappearance was noted at nightfall. The rescue was complicated by the location, the fact that he had already previously suffered a spinal injury, and snakes and other hazards in the area.

After the Michigan crash, he openly admitted to be considering retirement. Fittipaldi said that he had been given a message by the accident. Asked as to what that message was, Fittipaldi stated, "That I should stop." Although he later back-pedaled in late-1996 and early-1997 from his stating that he would definitely retire, a longer than expected convalescence made retirement more likely. Not long after the aircraft crash, Fittipaldi said, "Last year I received a message from God; this time it was an order."

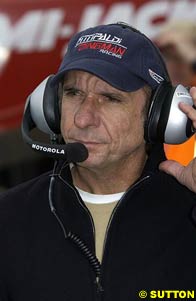

Emerson Fittipaldi not only won two CSI World Drivers' Championships and 14 championship races, he was also a champion of the Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART) series, twice winner of the Indianapolis 500, and has 22 CART wins. Yet, he is rarely mentioned by many modern F1 racing fans.

Emerson Fittipaldi was born on 12 December 1946 in Sao Paulo, Brazil. At the ripe old age of 25 he was the World Champion. Fittipaldi was a champion at the same age that Fangio first began competing in racing of any form. Fittipaldi was in many ways the prototype of the drivers who currently dominate F1. He started competing relatively early. At the age of 17 he began to compete in karts. He then moved into Formula Vee. All this time, Fittipaldi and his brother Wilson were involved in building karts, then Vees, and running a thriving accessory business.

In 1969, Fittipaldi left Brazil for Britain to compete in the Formula Ford series. Winning three of his first nine races in FF, Fittipaldi was tossed into the wild and wooly world of Formula 3. He emerged as the winner of the Lombank Championship and moved up the ladder once more in 1970 to Formula 2. He finished third in the F2 championship in 1970. However, he was offered a test in a Lotus by Colin Chapman in May. In July 1970, he was entered by Lotus in the British Grand Prix driving the team's third car, a 49. He finished in eighth place, but improved that result by placing fourth in the German Grand Prix in only his second Grand Prix race. He was entered in the Austrian Grand Prix and finished 15th, Lotus generally not having a good day.

1971 was a tough season for Gold Leaf Team Lotus. It was not helped by the fact that Fittipaldi was injured in a road accident near Dijon returning to his home in Switzerland. The injuries kept him out the Dutch Grand Prix, but he did mange to finish fifth in the seasons' standings. While the Grand Prix score remained at one, Fittipaldi won three F2 events.

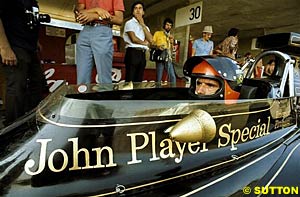

The 1972 season was clearly Fittipaldi's. Gold Leaf Team Lotus was now John Player Team Lotus and the Lotus was now called a "John Player Special" and painted black with gold trim - just like a certain brand of cigarettes. After spotting the opposition two rounds, Fittipaldi won the third round of the season (Jarama), the fifth round (Nivelles), the seventh round (Brands Hatch) - the aptly named "John Player British Grand Prix," the ninth round (Zeltweg), and the tenth round (Monza). In addition, he won the Daily Mail Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, the Daily Express International Trophy (Silverstone), the Gran Premio Republica Italia (Vallelunga), and the odd-ball 500-kilometer Brands Hatch event. Very much a man at the time of the heap.

In 1973, Fittipaldi came within a whisker of staying in the fight for the championship until the last, when his effort undone by teammate Ronnie Peterson. Fittipaldi then moved to McLaren and won the championship by that same whisker he needed the previous season. During 1975, Fittipaldi ran a distant second to Niki Lauda in the championship managing to add two more wins to his total. However, at the urging of his older brother Wilson, Fittipaldi left McLaren.

From 1976 through 1980, Fittipaldi and the Fittipaldi team struggled and struggled and saw only the odd flash of hope. There was some cause for a bit of hope when Fittipaldi did score some points in 1977 and 1978 and not ride drag on the herd. In 1979, the team scored exactly one point. In 1980, Fittipaldi retired from driving for his team and left Grand Prix racing. In 1982, the realities of diminishing resources and few willing to step forward to sponsor the effort coupled with poor to mediocre performance led to the Fittipaldi team being disbanded.

I have a tremendous admiration for both Juan Fangio and Emerson Fittipaldi. I could have gone on for many more pages providing a chronicle of Fangio's exploit's and how he stamped his mark on an era. Likewise with Emerson Fittipaldi. Both are fascinating men and lived their lives to the fullest.

While someone will be the youngest champion or another will be the someone with the most championships at the end of the Japanese Grand Prix, so be it. They will be men from a different universe than those whose names have suddenly once again appeared. Just different - not better, not worse, just different.

Life goes on.

We are now well into the second generation of racing fans to consider Formula One as both the Alpha and the Omega of motor sports. The records being - for the lack of any better choice - "threatened" at the Japanese Grand Prix are simply proof that sooner or later records get broken. Nothing more and nothing less.

Juan Manuel Fangio is perhaps still the personification of the ideal of not just Grand Prix racing, but motor racing. He faced greats such as Giuseppe "Nino" Farina, Alberto Ascari, Jose Froilan Gonzalez, Stirling Moss, Peter Collins, and Mike Hawthorn - and beat them all. Juan Fangio was revered during his era not because he was successful - which, of course, he was - but because he had a certain style, a way about him that made him as gracious in defeat as in victory. He radiated a sense of confidence that made no end of drivers concede victory before the flag even dropped. He was clearly the standard by which drivers measured themselves - and, in turn, fans the other drivers.

Juan Manuel Fangio is perhaps still the personification of the ideal of not just Grand Prix racing, but motor racing. He faced greats such as Giuseppe "Nino" Farina, Alberto Ascari, Jose Froilan Gonzalez, Stirling Moss, Peter Collins, and Mike Hawthorn - and beat them all. Juan Fangio was revered during his era not because he was successful - which, of course, he was - but because he had a certain style, a way about him that made him as gracious in defeat as in victory. He radiated a sense of confidence that made no end of drivers concede victory before the flag even dropped. He was clearly the standard by which drivers measured themselves - and, in turn, fans the other drivers.

Fangio simply excelled at the Carreteras events. He won in 1941 and 1942, the latter before the War brought an end to competition. After the War, Fangio picked up where he left off. In 1946, already 35 years old, returned to the fray of the great road races, but a move was now afoot to bring European-style racing to Argentina. This was to prove fortunate for Fangio.

Fangio simply excelled at the Carreteras events. He won in 1941 and 1942, the latter before the War brought an end to competition. After the War, Fangio picked up where he left off. In 1946, already 35 years old, returned to the fray of the great road races, but a move was now afoot to bring European-style racing to Argentina. This was to prove fortunate for Fangio.

As Fangio returned to Europe in 1949, two of the great drivers of the era were gone - Achille Varzi and Wimille. The former died at Geneva the previous Summer and Wimille during practice for a Temporada round. Later in 1949, Count Felice Trossi would die of cancer. But, a new star was rising in the form of Alberto Ascari.

As Fangio returned to Europe in 1949, two of the great drivers of the era were gone - Achille Varzi and Wimille. The former died at Geneva the previous Summer and Wimille during practice for a Temporada round. Later in 1949, Count Felice Trossi would die of cancer. But, a new star was rising in the form of Alberto Ascari.

In 1953, Fangio returned to the fray, at the age of 41. In late April, Fangio drove one of the new Alfa Romeo 6C300CM machines in the Mille Miglia with navigator/mechanic Giulio Sala. Driving a brilliant race, Fangio was in second place behind a bigger Ferrari driven by Giannino Marzotto. Approaching Bologna, the handling of the Alfa Romeo became erratic and the steering vague and at times, almost non-existent. The chassis was fractured at the point where the steering box was mounted. It worked well to the left, but when the steering wheel was turned to the right...

In 1953, Fangio returned to the fray, at the age of 41. In late April, Fangio drove one of the new Alfa Romeo 6C300CM machines in the Mille Miglia with navigator/mechanic Giulio Sala. Driving a brilliant race, Fangio was in second place behind a bigger Ferrari driven by Giannino Marzotto. Approaching Bologna, the handling of the Alfa Romeo became erratic and the steering vague and at times, almost non-existent. The chassis was fractured at the point where the steering box was mounted. It worked well to the left, but when the steering wheel was turned to the right...

On 28 July 1996, during the first lap of the Marlboro 500, Emerson Fittipaldi and Greg Moore touched slightly unsetting the handling of the Penske and Fittipaldi crashed heavily into the outside wall. The crash fractured his seventh cervical vertebra and required a high-risk, five hour operation to repair the damage the day following the crash. Fittipaldi was fortune to survive both the horrific crash - he hit the wall at a speed of nearly 200 mph - and the surgery. In addition to his broken neck, Fittipaldi broke his left shoulder and his left lung partially collapsed.

On 6 September 1997, Emerson Fittipaldi was hospitalized after suffering spinal injuries in a light airplane crash in his native Brazil. Piloting an ultralight aircraft with six-year old son Luca as a passenger, the aircraft crashed as Fittipaldi was flying over his citrus farm in Araraquara, Brazil. Luca suffered on very minor scratches as a result of the crash. Fittipaldi, however, suffered a lumbar fracture, which also resulted in partial paralysis of his left leg. Fittipaldi was flown to Miami for another round of surgery to repair his spine. The five hour procedure repaired the damaged vertebra and also relieved the partial paralysis of his left leg.

On 6 September 1997, Emerson Fittipaldi was hospitalized after suffering spinal injuries in a light airplane crash in his native Brazil. Piloting an ultralight aircraft with six-year old son Luca as a passenger, the aircraft crashed as Fittipaldi was flying over his citrus farm in Araraquara, Brazil. Luca suffered on very minor scratches as a result of the crash. Fittipaldi, however, suffered a lumbar fracture, which also resulted in partial paralysis of his left leg. Fittipaldi was flown to Miami for another round of surgery to repair his spine. The five hour procedure repaired the damaged vertebra and also relieved the partial paralysis of his left leg.

Fittipaldi was scheduled to compete in the Italian Grand Prix, but the fatal accident of championship-leading and Lotus team leader Jochen Rindt led to his entry being withdrawn. Not until the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen did Lotus and now team leader Fittipaldi return to the fray. In only his fourth start in a championship event, Fittipaldi took the checkered flag and assured that Rindt would emerge as the season's champion. Alas, Fittipaldi was the first to fall by the wayside in Mexico.

Fittipaldi was scheduled to compete in the Italian Grand Prix, but the fatal accident of championship-leading and Lotus team leader Jochen Rindt led to his entry being withdrawn. Not until the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen did Lotus and now team leader Fittipaldi return to the fray. In only his fourth start in a championship event, Fittipaldi took the checkered flag and assured that Rindt would emerge as the season's champion. Alas, Fittipaldi was the first to fall by the wayside in Mexico.

This left Fittipaldi pretty much a forgotten man. He tried his hand at IMSA racing and then found a ride in the CART series in 1984. In 1989, teamed with Pat Patrick, Fittipaldi won the Indianapolis 500 as well as the CART championship. Although he had been "there" - in CART - since 1984, most suddenly seemed to notice him that year. Fittipaldi captured his second Indianapolis victory in 1993. Generally being at the competitive end of the grid until his horrific crash at Michigan, Fittipaldi seems once again to have faded from contemporary memory. That is until the possibility that his "record" of being the youngest World Champion was challenged.

This left Fittipaldi pretty much a forgotten man. He tried his hand at IMSA racing and then found a ride in the CART series in 1984. In 1989, teamed with Pat Patrick, Fittipaldi won the Indianapolis 500 as well as the CART championship. Although he had been "there" - in CART - since 1984, most suddenly seemed to notice him that year. Fittipaldi captured his second Indianapolis victory in 1993. Generally being at the competitive end of the grid until his horrific crash at Michigan, Fittipaldi seems once again to have faded from contemporary memory. That is until the possibility that his "record" of being the youngest World Champion was challenged.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 41

Atlas F1 Exclusive

Interview with Pizzonia

Fisichella: Through the Visor

Atlas F1 Special

Rear View Mirror Special

Half a World Away

GP Preview

2003 Japanese GP Preview

Japan Facts & Stats

Columns

The Fuel Stop

The JV Trivia Quiz

Bookworm Critique

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |