Atlas F1 Contributing Writer

The Monza circuit is not only the spiritual home of Italian motor racing, but also the place where historic races have taken place since the first Grand Prix was held there in 1922. Journalist and historian Doug Nye takes a look at the history of this charismatic circuit to get a first hand feel of what it took to win at Monza

Perhaps cars would be out practising. If so as you descended into that tunnel a car might be heard being balanced on the throttle through the 180-degree Curva Parabolica - 'The Diabolica' as it was nicknamed by the Anglo-Saxons - away to the right. Then the hard, crisp, cutting note of that exhaust - flat-out - would keen through the September air, slamming by above your head and howling away to the left, unrelenting, screaming on, and on, and on, echoing back from the arching grandstand and long, low, pit block, away into the Curva Grande, in those days absolutely unfettered by an entry chicane. And you realised then that here was an engine tester, a place upon which Italian motor racing had been based, and grew and flourished and prevailed for so many years. Here you were at the home of those magical marques to whom the engine was everything, the chassis was merely an often inconvenient bracket intended to wed driver, engine, wheels and fuel load.

During the Second World War the great Autodrome suffered and crumbled, was battered and - since it became a major military vehicle concentration and stores lager - bombed. But Italian passion and heart and bravura prevailed, and in 100 days the place was restored to rude health for racing to resume.

The Italian Grand Prix returned there in 1948, and the other races followed, the national events for all kinds of car class, the Supercortemaggiore sports car classic, later the Monza 1,000 Kilometres World Championship sports car round - traditionally run on Italy's Liberation Day, April 25, and so on.

It was here at Lesmo in 1952 that a fatigued Fangio, clapped out after a hectic overnight drive from Lyons and arriving barely in time to start in the F2 Autodrome GP, rolled his works Maserati and broke his neck. That injury sidelined him for the rest of that season, and wrecked his hopes of defending his Drivers' World Championship title from 1951. It was here in 1955 that the mighty speedbowl of the Pista de Alta Velocita track featured in the combined road and track course which saw Fangio and Mercedes-Benz dominant. It was here in 1956 that Peter Collins surrendered his Lancia-Ferrari to teammate Fangio, enabling The Old Man to secure the fourth of his record five Drivers' Championship titles.

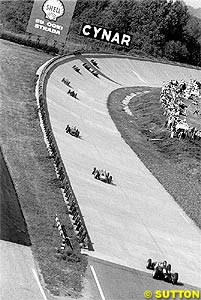

It was here in 1957-58 that Vanwall packed the front grid row, 1-2-3, to such Italian embarrassment that the grid was rearranged on a 4-3-4 basis to put a red car into prominence up front. And it was here in 1965 that Jackie Stewart scored the first of his contemporary record 27 World Championship-qualifying GP victories, that Jimmy Clark unlapped himself to regain the lead in 1967, only to run out of usable fuel and for Surtees's Honda finally to edge out Jack Brabham for victory. Here we saw Stewart clinch his first World title in 1969, in the Tyrrell Matra, with an eye-blink covering the first four cars past the flag. And here that the fastest postwar Grand Prix of all was won - only just! - by Peter Gethin and BRM in 1971.

More recently the list of triumph and endeavour and sparkling victory rolls on. Ferrari's resurgence, Williams failure by Damon Hill, McLaren failure by Mika Hakkinen, and wins by the boys too, by Damon and Johnny Herbert and Heinz-Harald Frentzen, surprise and drama interspersed by the usual suspects, you know, Ferrari, Schumacher, McLaren, Senna, Prost etc.

But right now I'm writing this fresh from a nostalgic weekend in the Goodwood Revival Meeting in England. There we staged a Graham Hill commemoration, to mark the 40th anniversary of the great double-World Champion's very first outright Formula One race victory, on Easter Monday 1962, in the famous 'stackpipe' BRM. Graham remains the only driver ever to win the Formula One World Championship, and the Indianapolis '500' and the Le Mans 24-Hours race, and as Damon Hill reminded me as he sat in a sister car of his late father's - he was also the only World Champion to have a son who subsequently became World Champion too.

For a first hand feel of what it took - and how it felt - to win the mighty Italian Grand Prix at Monza, here's the 1962 BRM team report of a memorable stepping stone along Graham's way to that year's Formula One World Championship titles:

16th September, 1962.

Three cars were taken to Monza. All were fitted with close ratio gearboxes and geared to pull at 158 miles an hour at 10,000 r.p.m.

Additional fuel tanks were fitted, together with quick action filler caps on the existing tanks. The oil tank capacity was increased; the size of pipe line from the tank to the engine was also increased and catch tanks fitted to the oil tank breather system, so that in all the cars carried an extra gallon of oil and an extra 4 gallons of fuel.

In order to reduce tyre wear front wheel camber was removed; rear wheel camber reduced to 1 degree, and rear toe-in to .1". All three cars were fitted with modified pistons and inlet camshafts on the exhaust side. The oil pumps had steel end plates and all internal oil ways in the oil system were increased in size by approximately 10%.

With this in view, engine No. 5606, which gave the best power on the test bed, was fitted to this car. On arrival at Monza, arrangements were made to run the cars on Thursday afternoon, the 13th September, before official practice, to check tyre wear, fuel consumption and gear ratios.

The drivers' initial reaction was that the cars were badly over-geared. Ginther's car only pulled 9,400 r.p.m. Graham Hill's old car, 9,600 r.p.m. and both Graham Hill and Ginther drove the spare and were of the opinion that it was going to 9,900/10,000.

Fuel consumption was in the order of 12 m.p.g. and tyre wear was very low. We, therefore, increased cambers by one degree, front and rear, and lowered the axle ratio on Graham Hill's old car and the spare, so that 10,500 r.p.m. became 152 m.p.h.. - and Ginther's car was lowered two ratios, whereby 10,500 became 148 miles an hour.

* * *

For official practice, G. Hill's numbers were put on the new car, and his old car carried the 'T'.

In the course of practice, G. Hill reported that his car was pulling 10,300 r.p.m. which is around 156 or 7 m.p.h. - very nearly our original estimate, and the engine felt very powerful. The oil pressure was, however, on the low side, which on the Oulton Park experience appears to be a fault on this car.

Ginther's car was going to 10,800 r.p.m. with ease, and he was then lifting off as he was afraid of over-revving the engine. He had no other troubles.

Graham Hill then drove his old car, which he said did not appear to have anything like the power, although the oil pressure was good and he much preferred the handling. The session concluded with G. Hill having achieved fastest practice time of 1 min. 40.8 secs, which carried a prize of 200.000 Lire.

Ginther was 6th fastest with a time of 1 min. 42.6 secs., having established this time towards the end of the session with full petrol tanks. Ginther said that although the car felt sluggish, it handled much better with full load than with the usual 10 gallons normally carried for practice. After Practice, it was found that the rate of tyre wear was still low; but that the fuel consumption was now only 11 m.p.g.

Graham Hill asked if the engine from the spare car could be fitted into his old car, as he was much happier with its handling - although he could not define any specific shortcoming on the new car, and he would feel happier in his old car.

As the reasons for low oil pressure could not be found, the engine was, therefore, removed from the spare car, fitted to Graham Hill's original car, and the spare engine was installed in the spare car, so that the build could be proved in the final practice session.

We also found that the high pressure pump on G. Hill's old car was down on performance, so that was replaced by the spare. G. Hill's numbers were transferred to the old car and the 'T' put on the spare.

During the final practice session, G. Hill did six laps in his own car, which he said was going exceptionally well, and going up to very nearly 10,800 r.p.m. He then tried the spare, which he said was also good - although the engine had not settled down it was going over 10,500 r.p.m.

Ginther then came in and complained that his engine was over-heating and the water temperature had gone up to 110 degs.C. when slip-streaming Clark. Some additional slots were cut in the body to assist the air to escape after having passed through the radiator - these had no effect - and Ginther reported that the temperature was fluctuating, which indicated that the water system was being pressurized, probably due to a blowing cylinder head joint.

Ginther was then wrapped up in sorbo and put in the spare car, and although he could barely reach the pedals and could only just see out of it, he produced a time of 1 min.42.l secs. The spare and Ginther's own car were, therefore, taken back into the paddock and as many cockpit fittings as possible transferred to the snare car in the time available, together with Ginther's Numbers.

Towards the end of practice, Jim Clark produced a time of 1 min. 40.4 secs. and Graham Hill also managed a time of 1.40.4; the timekeepers later corrected these times, giving Clark a time of 1 min. 40.35 secs. and G. Hill 1 min. 40.38 secs. Meanwhile Ginther had set up third fastest practice time of 1 min. 41.1 secs.

* * *

Pre-race checks were then carried out on the cars. It was decided that it was best to let Ginther drive the spare car, so the smaller brake cylinders which Ginther needs were transferred to the spare car.

No fault was found with Graham Hill's car during these checks; but the high pressure electric petrol pump on Ginther's car (the spare car that Ginther was to drive) was found to take nine amps instead of the maximum five. This was replaced. Fuel consumption then became a problem - as based on Graham Hill's fast laps, we would need 31.8 gallons for the race and his car only carried 31.5 gallons, and Ginther's car 30.9.

After the cars had been warmed up before the race, the fuel tanks were topped up, and fortunately the rubber bag tanks had stretched slightly, and we were able to get 32 gallons into Ginther's car and 32½ into G. Hill's. As the barometer was very low, i.e., 29" Mercury and air temperature had also dropped considerably, we had intended to weaken the mixture on both cars; but in view of the extra fuel we had got on board, it was decided not to alter the settings.

Graham Hill made a bad start, nearly stalling his engine - and over-revved it to nearly l2,000 r.p.m. before he got away. He found, however, that the engine seemed unaffected; and as he began to overhaul Jim Clark on the run from Lesmo to the Ascari curve, he decided to overtake him and went into the lead, which he retained until the end of the race.

Shortly after this the engine in Surtees's car blew up, which left Graham Hill in the lead some 30 seconds in front of Ginther, who in turn was 47 seconds ahead of the third man.

Towards the end of the race, both cars were given the slowdown signal. Ginther responded immediately and slowed down by one or two seconds a lap, while G. Hill did not slow quite so much at first - saying afterwards that as he had got into the rhythm, he found it very difficult; and although he was changing up at around 9,800 and braking much earlier, as his car used fuel, his lap times stayed about the same.

After the race, Ginther said he had no trouble with his car - his goggles had been damaged while fighting with Surtees, but he was able to change to his spare pair.

Graham Hill said that his car also ran well, although towards the end of the race the oil pressure began to fall off after cornering, and he assumed that this was because the oil level was getting low. The cars were sealed by the Scrutineers and we were unable to carry out the usual post-race checks until after The specified five days had elapsed. Tyre wear was relatively low - 3 min at the rear and 2mm. at the front on both cars.

1½-gallons of petrol was drained from Graham Hill's car and one pint from Ginther's. Both cars, of course, had completed an extra lap of honour. Slightly over two gallons of oil remained in Richie Ginther's car, but there was only one gall. and five pints in Graham Hill's.

Both engines were clean externally and it would appear that most of the oil used had got past the pistons. We did in fact find that No. 2 piston on Graham Hill's engine had a cracked skirt and the liner was badly scored, which would account for the higher oil consumption on this engine.

All the high pressure petrol pumps have been returned to Lucas's, who report that the 2 defective ones are suffering from deterioration of the electric motors, which is a new trouble. No faults have been found on the cars; but the injection metering unit fitted to the original engine in G. Hill's car was found to have gone off range on one shuttle.

24th September, 1962.

A. C. Rudd.

This fantastically dominant BRM 1-2 at the spiritual home of Italian motor racing sealed the BRM team's development into having become one of the strongest in Formula One. It was an immensely satisfying event for the creator of BRM - Raymond Mays - in particular, redressing as it did the memory of his original team's utter humiliation there eleven years earlier, when both of the centrifugally supercharged BRM V16s (the 'Great British White Hope') had been withdrawn before even reaching the start.

Graham absolutely revelled in his success: "The race was comfortable - I had never been in such a position before where I had a safe lead and on a circuit which takes a lot out of the engine - you are running flat out for most of the way. The race just seemed to go on and on, 310 miles long; I led for every lap, and, except for the first mile, I was in the lead all the time. It was a pretty satisfying race and a very convincing win."

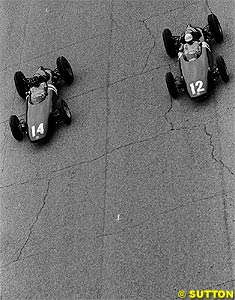

Raymond Mays recalled: "It was wonderful to see the electronic scoreboard on the Pirelli Tower showing cars 14 and 12 first and second, lap after lap. When they took the flag it was indescribable - complete joy. It was the finest victory ever for our team. It meant so much to me - I could now live at ease with the memory of having had to see the race directors and withdraw our cars at the last moment in 1951. So many people seemed to share our joy. My old friend Signor Bacciagaluppi, the Autodrome manager who had been so good to us over so many years, seemed as pleased as we were. Then we all stood for the national anthem - we had put two cars on that grid, and they had finished first and second, and crushed everybody else - including Ferrari and Porsche. It was simply wonderful."

Graham was surprised by how easy it had seemed: "I had never been in such a position before where I had a safe lead on a circuit which takes a lot out of the engine - you are running flat out for most of the way. The race just seemed to go on and on, over 300 miles; I led for every lap and, except for the first mile, I was in the lead all the time. That was a pretty satisfying race and a very convincing win."

Fuel requirement for this long, fast race had posed a real threat. The roll-over bar on the P578 cars doubled as part of the fuel tank breather system and when they had gone to the startline at Monza they both had fuel brimming halfway up that tube.

Graham Hill and BRM were now leading the Championship and really were ready to fight Jimmy Clark, Team Lotus and Coventry Climax for the twin titles, all the way to the wire...

No such luck this year - fellow Formula One fans - but look at the place, the ambience, the majesty of the stage. Three out of four can't be bad, can it?

If Formula One has a spirit - and I believe it has indeed - then Milan's Monza Autodrome, primary home of the annual Italian Grand Prix since 1922, is surely its spiritual home. For years as one drove or walked into the wooded Royal Park and passed through the entry tunnel onto that historic infield with its porphyry-paved paddock, the short hairs on the back of one's neck would bristle.

Here you were at a circuit which had seen it all. It had seen triumph and tragedy and vindication and disaster, often in disproportionate degree. The courses here had been varied and variable over the decades. When the silver German cars of the 1930s demonstrated every sign of breaking Italy's stranglehold on Grand Prix success, so the course had been juggled and fiddled, diversions built in, chicanes introduced - all of this decades before the machinations of the FIA, Balestre, Bernie and Mosley. Still the Hun won.

Here you were at a circuit which had seen it all. It had seen triumph and tragedy and vindication and disaster, often in disproportionate degree. The courses here had been varied and variable over the decades. When the silver German cars of the 1930s demonstrated every sign of breaking Italy's stranglehold on Grand Prix success, so the course had been juggled and fiddled, diversions built in, chicanes introduced - all of this decades before the machinations of the FIA, Balestre, Bernie and Mosley. Still the Hun won.

Italian Grand Prix, Monza Autodrome, Milan - 86 laps, 307.28 miles

Cylinder heads were re-profiled around the valve seats to give maximum gas flows through inlet and exhaust ports. Re-built high pressure petrol pumps were used with increased performance. Big end bolts and tappets were replaced in all engines. It was our intention that Graham Hill would drive the latest car, which has slightly less frontal area than the older cars, which thus should be a little faster.

Cylinder heads were re-profiled around the valve seats to give maximum gas flows through inlet and exhaust ports. Re-built high pressure petrol pumps were used with increased performance. Big end bolts and tappets were replaced in all engines. It was our intention that Graham Hill would drive the latest car, which has slightly less frontal area than the older cars, which thus should be a little faster.

Rear camber was increased by ½ degree on Graham Hill's old car, and the later type oil filter from the spare car, which was suspect due to the report of low oil pressure, was dismantled and a number of detailed modifications made to increase its oil through areas.

Rear camber was increased by ½ degree on Graham Hill's old car, and the later type oil filter from the spare car, which was suspect due to the report of low oil pressure, was dismantled and a number of detailed modifications made to increase its oil through areas.

Ginther also found himself able to slipstream Jim Clark and keep up with him. After Clark's stop on the 3rd lap, Ginther then carried out his instructions, which were to do everything he could to help Graham Hill get clean away. After 20 laps, when G. Hill had a lead of some 17 seconds, Ginther decided that if he speeded up he would tow Surtees to within striking distance of Graham Hill. He, therefore, kept going at the same speed and waited for an opportunity to lose Surtees, which occurred when they lapped Masten Gregory in the south turn. Ginther managed to pass him in the corner and was able to draw away, at the rate of a second a lap.

Ginther also found himself able to slipstream Jim Clark and keep up with him. After Clark's stop on the 3rd lap, Ginther then carried out his instructions, which were to do everything he could to help Graham Hill get clean away. After 20 laps, when G. Hill had a lead of some 17 seconds, Ginther decided that if he speeded up he would tow Surtees to within striking distance of Graham Hill. He, therefore, kept going at the same speed and waited for an opportunity to lose Surtees, which occurred when they lapped Masten Gregory in the south turn. Ginther managed to pass him in the corner and was able to draw away, at the rate of a second a lap.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 8, Issue 37

Articles

Juan & Kimi: The Odd Couple

Giancarlo Fisichella: Through the Visor

Jo Ramirez: a Racing Man

Italian GP Preview

Italian GP Preview

Local History: Italian GP

Italy Facts, Stats and Memoirs

Columns

Italian GP Quiz

Rear View Mirror

Bookworm Critique

Elsewhere in Racing

The Grapevine

> Homepage |