Atlas F1 Associate Writer

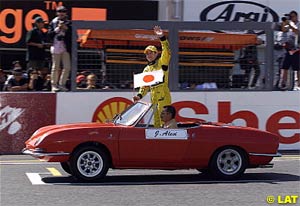

Jean Alesi was the antithesis of the modern PR-obedient professional, a throwback to another age and another generation, a time when all the clichés about Grand Prix drivers were recited without a cynical smile. He only scored one GP victory, but he was loved and worshipped as a World Champion. After his retirement from Formula One, Timothy Collings pays homage to the volatile Frenchman

That is why, in the summer of 1995, when he entered a popular Italian restaurant in Montreal's fashionable district packed with bars and the beautiful, he received a standing ovation. The eating house, with a romantic name, was packed to its capacity with around 250 people and they all stood to applaud as the larger of two small dark-haired Frenchmen, both showing signs of embarrassment, were shown to a table in a corner. Alesi was with his soon-to-be-wife Kumiko and his old friend and future employer and ex-employer Alain Prost, also a former teammate at Ferrari.

It was, of course, Alesi's 31st birthday. But that was not the reason he received such appreciation from the massed French-speaking Canadians. That afternoon, Alesi, driving Ferrari number 27, had won his only Formula One Grand Prix race, on the circuit named after the man whose pyrotechnic ability had turned that number into something of legendary status for the Italian team: Gilles Villeneuve. The father of Jacques, who won the Drivers' Championship in 1997 for Williams, had also been a good friend of Prost's, and that sunny Sunday afternoon at the island in the Great St Laurence seaway, in an hour of memories, Alesi had completed a triumph of almost perfect emotional intensity and neat symmetry.

It was equally enjoyable for many that day to see Rubens Barrichello and Eddie Irvine finishing second and third for the Jordan team, thereby supplying them with their first significant podium finishes, because it had been Eddie Jordan who had provided Alesi with the platform to launch his career by running him successfully in the International Formula 3000 Championship of the late 1980s. Even then, in 1988 and 1989, he was a driver with his own individual way of doing things as he collected three wins on the way to his F3000 title in 1989 and a debut with the Tyrrell-Ford team at the French Grand Prix that year down at Le Castellet. Few then, certainly not Alesi, would have imagined he was embarking on a career that would end in Suzuka in 2001, after 201 Grands Prix. "There won't be another one like him, will there?" smiled McLaren's David Coulthard, with whom Alesi had many a battle, as the curtain descended on arguably the most colourful and enlivening career of modern times. "They're not made like it now."

To many, in these cold and clinical times, when money rules all, the continued existence of Alesi, as a showman, must have seemed almost anachronistic. But he touched the hearts. He was too generous. Too flamboyant. Too unreliable. Too focussed on racing and too crazy by half. But he was loved. The only driver to list Vichy Menthe as his favourite drink, he had a fund of stories involving himself, best told by others, that reflected an age and an attitude long gone. Like the time, on September 11, 1994, when he took pole position at Monza, in his Ferrari, for the Italian Grand Prix. It was only some five months after the terrible weekend at Imola, on Formula One's previous visit to Italy, but Alesi was able to demonstrate a level of passion and commitment that both Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna would have appreciated.

When the race started, Alesi took the lead. Driving like a man possessed, he led for 14 laps before pitting. His teammate, his friend and colleague in the unofficial world championship of practical jokes and daft pranks, Gerhard Berger, inherited the lead for Ferrari. But it was not a routine or a satisfactory pit-stop and, as a result, Berger and the rest of the Ferrari team were not to see Alesi again that day. Instead of re-joining the race, he found himself frustrated and then furious as his car was wheeled in and he retired. A normal scenario for Ferrari at the time - a flash of glory and then withdrawal - had conspired to take the taste of glory out of the dashing Frenchman's mouth.

Alesi could not believe it. Still wearing his overalls, pulling his helmet off and hurling it aside, with his brother Jose in hot pursuit, he stormed through the garage and out towards the car park, to his waiting Alfa Romeo 164. He drove it hard, fast and true towards Avignon where his family lived and promised a peaceful retreat.

The next day, at a favourite local café-bar, Alesi called in late in the morning for a drink. The barman complimented him on his speed the previous day. Alesi, surprised, asked what he meant as he had done only 14 laps and then retired. The barman said he meant his speed on the autostrada, from Milan to Provence, through the police traps, which had clocked him at upwards of 220 km/h, where the men in uniform had preferred to salute a hero rather than arrest a villain of the road. He lifted a copy of the front page of the local newspaper up for inspection to allow Alesi to see the story. The racer, typically, did not know if he should laugh or cry; an experience most of his friends and admirers will have grown to understand well down the years.

For not only was Jean Alesi a great and glorious racing driver, but he also remembered his friends and, for that, he meant nearly everyone around him in the paddock. To Alesi, Formula One was a sea of smiles, not a stiff-jawed arena of competition. It was a joyous experience to be shared and loved. Each year, at Christmas, he remembered the kindness of Frank Williams, who had signed him for 1991 before he changed his mind and went to Ferrari. Then, he was the hottest driver of the day. Williams was disappointed, but a gentleman. Alesi valued the human level of Williams behaviour, and every winter he sends him a case of champagne. He also sends Christmas cards, signed by hand, to the vast majority of his Formula One friends.

He checked that the young Sauber driver was unhurt and then shook his hand warmly. It was a gesture that symbolized a transfer of charisma from one generation to the next. It showed Alesi at his greatest, caring about something else, someone else, showing the kind of humanity that punctuated the crazier happenings in his career. Perhaps, after the way they parted this year, Alain Prost will feel differently, but he knows too that Alesi acted, as usual, on impulse when he left to go to Jordan to end his days. How sad, indeed, that he won only one race. But how wonderful he could walk away happy at the end.

It does not matter if you loved him or not, any Formula One follower with reasonable vision and an everyday appreciation of the drivers' arts and antics will miss Jean Alesi next season. He was the antithesis of the modern PR-obedient professional, a throwback to another age and another generation, a time when all the clichés about Grand Prix drivers were recited without a cynical smile. And no-one, but no-one, had a temper tantrum like Alesi. If he was cross, anyone standing close by would make the sign of the cross, and duck....

But Alesi was much more than just a temperamental superstar with a fiery personality, amazing car control and a searing sense of personal ego. He was an uncluttered human being, a man who made decisions in haste and repented at his leisure, someone for whom wisdom was always an afterthought. Talk, even briefly, to any of his teammates, or his former technical directors or race engineers, and only the mention of his name will bring forth a smile. The memories of Alesi are legion in every team for which he raced. And that same magic rubbed off on the crowds - in this case, the spectators at the circuits, the real fans, who loved to see him throwing his car at everything. If Alesi was racing, in a half-decent car, with half a chance of anything, he always gave full value for money.

But Alesi was much more than just a temperamental superstar with a fiery personality, amazing car control and a searing sense of personal ego. He was an uncluttered human being, a man who made decisions in haste and repented at his leisure, someone for whom wisdom was always an afterthought. Talk, even briefly, to any of his teammates, or his former technical directors or race engineers, and only the mention of his name will bring forth a smile. The memories of Alesi are legion in every team for which he raced. And that same magic rubbed off on the crowds - in this case, the spectators at the circuits, the real fans, who loved to see him throwing his car at everything. If Alesi was racing, in a half-decent car, with half a chance of anything, he always gave full value for money.

The older observers knew what the Scot meant, but for some of the younger generation, fed on tales of Jenson Button, Kimi Raikkonen and the rest, it must have seemed difficult to understand. Alesi, to them, after all, was an old-stager, in the dying days of a long and relatively unsuccessful career. Hopefully, the younger ones will have noted that Frank Williams smiled at the memory of his brushes and experiences with the volatile Frenchman of Sicilian descent, that Alesi drove for Ferrari with his heart, that Gerhard Berger could only grin broadly at some of his most vivid memories, and that men from all quarters of the grid and the paddock walked to greet him and say farewell.

The older observers knew what the Scot meant, but for some of the younger generation, fed on tales of Jenson Button, Kimi Raikkonen and the rest, it must have seemed difficult to understand. Alesi, to them, after all, was an old-stager, in the dying days of a long and relatively unsuccessful career. Hopefully, the younger ones will have noted that Frank Williams smiled at the memory of his brushes and experiences with the volatile Frenchman of Sicilian descent, that Alesi drove for Ferrari with his heart, that Gerhard Berger could only grin broadly at some of his most vivid memories, and that men from all quarters of the grid and the paddock walked to greet him and say farewell.

Not many of them are like that. Remember too that Alesi may have ended his 201-race career at the top, with a spectacular collision with Finland's rising star, Kimi Raikkonen, but he survived unhurt, physically unblemished, and with the same emotional approach as when he started. And remember the scene when, after his massive collision with the Finn's Sauber, he stopped waving to the crowd and went to console Raikkonen, who sat with his head in his hands on a nearby bench.

Not many of them are like that. Remember too that Alesi may have ended his 201-race career at the top, with a spectacular collision with Finland's rising star, Kimi Raikkonen, but he survived unhurt, physically unblemished, and with the same emotional approach as when he started. And remember the scene when, after his massive collision with the Finn's Sauber, he stopped waving to the crowd and went to console Raikkonen, who sat with his head in his hands on a nearby bench.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 7, Issue 44

Articles

Jean Alesi: One in a Million

Commentary

Reflections on 2001

2001: Rubber and Class

A Season in Waiting

2001 Season Review

The End of Season Report

The 2001 Technical Review

The 2001 Season in Quotes

How Would F1 Score in Other Series

Columns

The 2001 Qualifying Differentials

2001 Season Strokes

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |