Atlas F1 Columnist

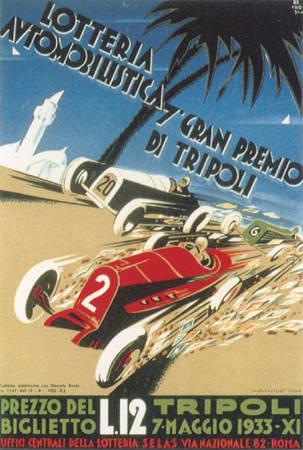

There are few stories in motor racing more enduring than that of the 1933 Tripoli Grand Prix. Don Capps tells the story of that race. The real story, that is...

In the 1962 movie, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, James Stewart portrays a Senator and former governor who has returned to his home state for a funeral. The Senator has earned his reputation on the strength of being the 'man who shot Liberty Valance.' Liberty Valance, played by Lee Marvin, is about as dastardly a villain you can find. Liberty Valance does about every evil act one can imagine except drown kittens and only that is omitted because of the director didn't think of it. In a showdown of epic proportions, Stewart manages to shoot Liberty Valance, whose death makes the territory a safe place for little boys and girls and the home folks. After the funeral, as he returns by train to Washington, Stewart begins a tale to several reporters about himself and the man they have just buried -, who is portrayed by "The Duke," John Wayne ("...well, Pilgrim..."). Stewart reveals that it was not he who "shot Liberty Valance," but Wayne. At the end of the tale, a young reporter asks a veteran reporter what to do about what he has just heard. The older and more experienced reporter tells the young reporter that when faced with printing the truth or the legend, "...always print the legend."

There are several enduring stories in motor racing. They get repeated as the years go by since new audiences appear and are introduced to such stories as the lore of motor racing. Excellent example are: Jimmy Murphy winning the 1921 Grand Prix d'Automobile Club de France in a Duesenberg; Tazio Nuvolari beating the mighty German teams in his Alfa Romeo Tipo B at the 1935 Grosser Preis von Deutschland held on the Nurburgring; Juan Fangio and his great come-from-behind victory at the same circuit in 1957; Stirling Moss defeating the Ferrari team at Monte Carlo in 1961; Gilles Villeneuve and his amazing victory at the 1981 Spanish Grand Prix; and, naturally, many others. One, however, seems to attract special attention.

The story of the 1933 Tripoli Grand Prix has been told and re-told many times. The story appears in periodicals and books as diverse as Sports Car Graphic, Ford Times, Car and Driver, Autosport, Automobile Quarterly, Road & Track, Motor Sport, and Power and Glory, to name but a few. The articles are written by authors such as Charles Proche, William Court, Charles Fox, Eoin Young, Richard Garrett, Chris Nixon, Mark Hughes, and Rob Walker, to name again but a few. With such a stellar group of talent, it is little wonder that most have accepted the story at face value. It is certainly difficult not to!

What is repeated time and again as the story of the Tripoli race has it origins with a very likeable, entertaining, and most surprising source: Alfred Neubauer, the manager of the triumphant Mercedes-Benz teams both before and after the Second World War. The story is found in a chapter of his 1958 book, Speed Was My Life (Maenner, Frauen und Motoren: Die Erinnerungen des Mercedes- Rennleiters Alfred Neubauer). That chapter is entitled, "The Race that was Rigged." It is unusual that we can trace the origin of a myth with such certainty.

Exactly what Neubauer had in mind when he wrote the chapter is unclear. First, he wasn't even at the race, hence had no first hand knowledge of what actually transpired. Second, Neubauer was a renowned raconteur and apparently was not above "spicing" up a story from time to time to make it "better." While I am certain that there was perhaps at least some reason for Neubauer spinning such a tale, I am at a loss to find it or offer a plausible reason as to his motivation for putting it in his book. Whatever his motivation was, Neubauer definitely inspired many with his tale.

With motor racing a popular sport among Italians, in 1926 a racing circuit is constructed outside of Tripoli, the capital of the colony. From 1925 until 1930, races are held which despite some early moderate success, quickly become financial flops. The 1929 race is held only due to direct intervention of the governor, Emilio de Bono, who manages to persuade sponsors to back the event. However, the last race held in Tripoli, 1930, was a financial disaster with the deadly combination of a small field 12 cars on the grid, racing over a long 26.2 kilometer circuit, a small crowd, and the death of a very popular driver Gastone Brilli Peri, the previous year's winner resulting in the organizers being unable to hold a race the following two years.

Undaunted, the president of the local auto club in Tripoli, Egidio Sforzini, organizes another attempt at a race in the Tripoli. This time it is an "European" type circuit, and built for the sole purpose of racing much like Montlhery, AVUS, or the even the Nurburgring. However, the money is tight and available only due to the government pouring money into a fair promoting the colony. The money for the new circuit is allocated only as a side attraction to entertain the tourists.

Meanwhile, an Italian journalist is musing on both the new Mellaha circuit and the very popular Irish Sweepstakes. Rather than a lottery based on selling chances to be selected as the holder of the ticket for the winning horse in the Irish Sweepstakes and thus win the jackpot, Giovanni Canestrini thinks the same scheme can be applied to a motor race. Canestrini is the editor of La Gazzetta dello Sport, one of the most popular sporting papers in Italy. His opinions and ideas carry weight in the Italian sporting world. Egidio Sforzini, is approached by Canestrini with the scheme for a sweepstakes a lottery in conjunction with a race in the Spring of 1933.

The lottery will supply much needed money for the new circuit, the coffers of the Automobile Club di Tripoli, and provide both enormous publicity for Libya and large crowds for the race. Canestrini is offering Sforzini an idea that is simply too good to resist. Keep in mind that the Mille Miglia is another scheme that Canestrini masterminded. Sforzini envisions a truly modern racing circuit, one that will use lights for the start, a photo-electric timing system, and generous facilities for both the participants and the spectators.

Sforzini, who is enthusiastic over the idea, agrees to the plan. Canestrini then takes the idea to Governor Emilio de Bono, an old acquaintance from prior to The Great War. Bono, soon to be the Colonial Minister in the government, is willing to entertain any notions that might help develop the prospects of Libya. De Bono is also enthusiastic over the scheme and then lends his support to the Automobile Club's Canestrini's plan. This sets the wheels in motion to bring the idea to fruition. The appropriate agencies pass the idea upward and upward until where it finally reaches Mussolini. Mussolini reviews the sweepstakes scheme and personally approves it.

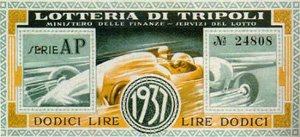

On 13 August 1932, aboard an Italian naval vessel, the Savoia, Royal Decree 1147 is signed by King Vittorio Emanuele III authorizing the lottery. The lottery tickets will be sold for 12 lire and the proceeds used to promote Libya and fund the race. When de Bono departs to accept his new position in the Fascist Government, the new governor, Pietro Badoglio, is briefed on the scheme and endorses it as well.

The Lotteri dei Milioni and the Corsa dei Milioni are off and, well, running. The first lottery tickets go on sell in October 1932 and the last date for selling the tickets is 16 April 1933. It is unclear exactly how much the lottery raised. Whatever the amount was, it was a huge amount of money for the time in Italy. To the best of our knowledge, the lottery "cleared" (to use Canestrini's term) at least 15,000,000 lire. That is an astounding number of 12 lire lottery tickets.

According to Canestrini, the breakout of the money went this way: 1,200,000 lire to the AC di Tripoli for its expenses; 550,000 lire for starting and prize money; and, 6,000,000 lire to the winners holding the tickets of the top three finishers win, place, show in the race. First place was worth 3,000,000 lire, second place 2,000,000 lire, and third place 1,000,000 lire. These are not small numbers in 1933. As the Poet once noted, "Gold drives a man to dream...."

And, the prize money for the race at least a sizable chunk of the 550,000 lire mentioned by Canestrini was very, very generous. In most cases the prize money for a race at this time was quite small, usually being paid only for the top several positions, with the "real" money being paid out was the start or appearance money. In this case, the prize money was enough to guarantee that there was some very serious money to be made by finishing well in the Corsa dei Milioni. Needless to say, nearly all the top teams, especially the Italian ones, were there.

When you add up the numbers Canestrini uses, it comes out to 7,750,000 lire. This is slightly over half of what was claimed to be collected by the sale of the tickets. What happened to it? While Canestrini or anyone else does not mention it specifically, the remainder was apparently "overhead." This might be a polite way of saying that given the tenor of the times, it went into the pockets of some of the big shots in the Fascist government.

The counter-foils of the lottery tickets were sent to Tripoli for the drawing several days after the last ticket was sold. The drawing was held on Saturday, 29 April 1933, eight days prior to the race. It was supervised by the governor, Pietro Badoglio. Each of the 30 entrants Giuseppe Bianchi was to apparently withdraw after the drawing took place in the race had a ticket drawn and assigned to that entry for the race. After the assignment of the tickets to their entries, the ticket holder was notified by a telegram from the organizers. There is sufficient time to ponder the wealth that awaited the winner of the lottery. There is also plenty of time to seriously consider means to narrow the odds.

This was, as mentioned, on a Saturday and the day prior to the running of the Gran Premio di Alessandria. The attention centered on the Tripoli race is blamed for the relatively poor entry by the organizers of the Alessandria race. Plus, there is the fact that Varzi was not allowed to participate in the race! Although he arrived at the circuit and was allowed to practice, his entry had arrived too late and he was denied a spot on the grid. Nuvolari won the event from Carlo Trossi and Antonio Brivio.

Now we get to the interesting part and here you find that when money talks, nobody walks. In an account recorded by Aldo Santini in his biography of Nuvolari, Santini uses notes taken from his interviews with Varzi to reconstruct the events surrounding the Tripoli race. Since Varzi had nothing to gain from being untruthful, there is a strong tendency to that him at his word. We also have what Canestrini says and additional information from Johnny Lurani.

At some point on the same day of the drawing, Nuvolari apparently contacted Canestrini about a meeting. Both were in Alessandria for the Gran Premio. Canestrini and Nuvolari met, but also present were Varzi and Borzacchini. Canestrini later claimed the topic of the meeting was the discussion of travel plans to the Tripoli race the following weekend. However, Varzi said that the only topic discussed was the race the next weekend in Tripoli and the lottery. However, while Santini states that also present are the ticket holders of the of the Nuvolari, Varzi, and Borzacchini entries in the race, it is thought that this is not the case.

Obviously there is some confusion here. It is possible that Canestrini was being evasive. Canestrini was not universally revered. His habit of writing a race report sitting in his comfortable office at the newspaper while supposedly at the event was known to many of the other journalists and eventually his readers. Canestrini says he was unaware of the "true" meaning of Nuvolari pointing his finger at him while on the grid at Alessandria telling him to remember the meeting the day in Rome. He states that his assumption was that the meeting was to discuss the travel plans for the following weekend. He then goes on to say that Varzi set him straight. Canestrini states that Varzi informed him that the meeting as to discuss the lottery, not the travel plans for the race.

The three drivers Nuvolari, Varzi, and Borzacchini, the three ticket holders, and Canestrini did indeed meet, but the meeting was in Rome early in the week following the drawing, on Monday evening. The site was the Massimo D'Azeglio near the Termini station, one of several hotels owned by fellow racing driver Ettore Bettoja, who also served as the host for the meeting. Canestrini states that he was asked to be present for the meeting to ensure that there was a neutral party who could arrange the terms to avoid any conflict with the regulations. In some accounts, Bettoja is named as the lawyer or notary who brokered the agreement. While Bettoja was indeed present, he was acting only as the host and providing the room for the meeting.

Johnny Lurani supports the fact that Canestrini was indeed the mediator who negotiated the agreement between the holders of the tickets. What is rather murky is how the three ticket holders got together. It is entirely possible that Nuvolari may have spoken to Canestrini in Alessandria to make the arrangements. Naturally, Canestrini is quiet on any such notions.

Valerio Moretti gives the name of the holder of the ticket for Nuvolari as Alberto Donati, of Cellino Attanasio, Teramo. The man who drew the ticket for Varzi is usually given as Enrico Rivio from Pisa largely on the strength of the Neubauer account of the race. Moretti gives his name as Arduino Sampoli from Castelnuovo Beradegna, Siena. The holder of Borzacchinis ticket is given as Alessandro Rosina from Piacenza. It with these men and the three drivers that Canestrini negotiated the agreement.

Again, as Varzi recounts, the meeting was held to discuss the very specific topic of how, "to find a formula which did not contravene the sporting rules," to divide the lottery money among what became known as The Six. This was scarcely a secret meeting. The 15 May 1933 issue of Moteri, Aero, Cicli e Sport reported not only that the meeting had taken place, but that someone had approached Piero Ghersi with an offer of 1,000,000 lire if he won the race. Others have Tim Birkin being offered either 70,000 or 100,000 lira by his ticket holder if he won the race.

According to Moretti, The Six as some were to call them formed a syndicate which pooled the prize money from the lottery and which would be split equally among them, as long as one of the three drivers won the race. The idea is generally credited to Donati. The drivers would receive half of the winnings of the syndicate, again to be split equally among those involved. And they also, something to remember, got to keep any of the prize money won as well.

Once the parties agreed to the arrangement they had discussed, it was also agreed that it should be put in writing. Apparently Canestrini wrote up the agreement and had it signed by all the participants. According to Canestrini, once signed by The Six, a notary reviewed and notarized the document. In any case, the manager of the local branch of the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro was summoned and given the document to either notarize according to some accounts or to hold until the appropriate moment. The agreement was then deposited in the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro for safekeeping.

The important outcome of the meeting was that there was to be no pre-arrangement in the document as to the outcome of the race. Canestrini and Lurani both make a point of stating this. There was no flipping of a coin or any discussion about who should win. What was decided was that regardless of whether Nuvolari, Varzi or Borzacchini won the race, the jackpot was to be split evenly among The Six. As long as one of the three drivers won the race, each member of the syndicate would receive approximately 500,000 lire regardless of who finished first. Add another 333,000 lire if one of the three drivers also finished in second. 833,000 lire is a good haul for one race in 1933.

Even before the meeting the sporting papers were printing reports which are nearly identical in content about the purpose and probable outcome of the meeting. That is, all except one, La Gazzetta dello Sport. And the absence of such reports was remarkable, since its motor sports editor was none other than guess who? Giovanni Canestrini! Indeed, La Gazzetta alone among the sporting journals of the day is strangely quiet about the entire affair. One can't help but wonder why... .

Interestingly enough, the whole thing was quite legal, even if somewhat questionable in terms of judgement. One point made very clear later was that Nuvolari's entrant, Enzo Ferrari, was not a party to the proceedings. Indeed, on 15 May, Ferrari according to Moretti had Nuvolari issue a statement making it clear that "...the Scuderia Ferrari was extraneous to the agreement with the ticket-holder paired with his name." Whether Ferrari was upset with the financial arrangements being made without his involvement or on moral grounds is somewhat unclear, but one senses it is the former.

So finally, The Six arrive in Tripoli for the race. Many of the other drivers are quite unhappy about the "arrangement" and were quite vocal about it. Campari and Fagioli are especially hostile to Varzi and Nuvolari. Both make it clear that they are determined to win the race and ruin it for the "conspirators" and the "coalition." Birkin may also among those whose speed may not have entirely due to simply trying harder, pour le sport. Canestrini mentions Birkin among those who wanting to win the race to upset the apple cart.

It is interesting to note that Lurani points out that Campari and Gazzabini were turned down in attempts to make similar deals with their ticket holders. Campari and Birkin then entered into a personal agreement to foil the efforts of the "conspirators." Gazzabini was very unpleasant towards Varzi and Nuvolari, heaping scorn on them and making threats.

According to Canestrini, Varzi responded by saying, "Do whatever you like, I will drive my own race." Nuvolari in particular seemed to be impressed by the vehemence directed at Varzi, Borzacchini and himself. In an effort to calm matters down, Nuvolari promised the other drivers to play "50/50." Canestrini goes on to record the answer Nuvolari gave when asked by Varzi how he could make such a promise, "It is quite simple: since you can't make 50/50 with everyone it is evident that I will share with nobody."

Lurani does not mention the coin toss to decide the winner. However, as usual, it is Canestrini who supplies the story. Varzi was quite aware that Campari and several others were counting on the often heated rivalry between himself and Nuvolari to result in the both of them taking each other out of the race. According to Canestrini, Varzi approached him on the morning of the race about his concerns that Nuvolari might forget about the money and re-heat the feud and cause them to lose all that money.

Varzi and Canestrini then went to see Nuvolari and this concern was laid out and discussed. Nuvolari said he understood and proposed that Canestrini toss a coin and the winner would be the one to cross the line first. The agreement with the ticket holders and the money was more important than the victory itself. Varzi agreed to the solution. Canestrini tossed the coin and Varzi won. Nuvolari then agreed to honor the arrangement. Borzacchini apparently was never consulted about the coin toss or any finishing instructions as far as we know.

The 29 entries lined up on the grid in the order determined by the drawing of ballots, which also determined the race numbers. For some reason, Borzacchini and Cazzangia lined up out of numerical sequence. Once the grid was formed, Governor Badoglio pressed the button to activate the starting lights.

When the starting lights came on, Carlo Cazzangia took off like a rocket in his Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 grabbing the immediate lead. However, as the field came around to complete its first lap, Birkin was leading the race. Birkin was followed by Nuvolari, Giuseppe Campari (works Maserati 8C-3000), Goffredo Zehender (Raymond Sommer-entered Maserati 8CM) who started from the fifth row, pole-sitter Premoli, and the rest of the pack. When the field came round the next time, it was led by Campari who passed both Nuvolari and Birkin and was starting to already draw out a cushion. On this lap Luigi Fagioli peeled off and pitted his Maserati 8CM for a plug change. Varzi is nursing his Bugatti along on seven cylinders due to the mechanics topping off the engine with oil at the last minute and overfilling the sump, a not uncommon problem with the Bugatti it seems. The experienced Varzi realized that once the oil level was reduced, it would probably start running on all eight cylinders.

Just short of the halfway point, 14 laps, Campari pitted. His oil tank was coming adrift and causing problems with lubricating the engine. After several quick, frantic attempts to bolt it in place, the offending tank was secured in place with rope found in the pits. However, after several more laps Campari was forced back into the pits to deal with the offending part. Yet another attempt to make further repairs was halted once it became apparent that the lack of oil had produced a death rattle in the engine of the Maserati. Campari did not give up easily. His efforts to win were obviously stirred by his anger towards Varzi and Nuvolari.

On the same lap that Campari originally pitted, so did Birkin. Birkin pitted his Maserati to refuel. The stop was utterly routine, the only drama being Birkin accidentally getting a burn on his arm from the exhaust pipe, an all too common occurrence and an occupational hazard in those days. As noted, it was done quickly and with minimal fuss. Neither Canestrini nor the report in Motor Sport mention anything out of the ordinary about his pit stop.

When Campari pitted, Nuvolari swept into the lead. Varzi and Zehender were in second and third places, and Birkin, in fourth and going very well and showing no apparent ill effects of the burn suffered during his pit stop. After 23 laps, Nuvolari roared into the pits for the modern equivalent of a "splash-and-go." The pit stop itself took only 20 seconds, quite a remarkable time when it is realized that most pit stops of the day were measured in minutes. However, it cost him about a minute entering, stopping, and then leaving the pits. The Varzi Bugatti, as it turns out, is fitted with an additional fuel tank and Varzi is planning to avoid a pit stop and run the race non-stop.

Nuvolari screams out of the pits roaring after Varzi. Over the last several laps of the race Nuvolari carved big chunks of time off the lead Varzi had built up. Some of the time was gained when Varzi experienced difficulties switching to the spare tank. Canestrini stationed himself on the Tagiura Curve so as to both keep an eye on Varzi and Nuvolari, but also signal to them to remember the agreement. As Varzi struggled with his fuel tank switch, Nuvolari finally managed to not only catch Varzi, but actually pass him. Nuvolari, under the clear impression that the deal was off since Varzi was apparently in trouble, had the bit in his teeth and going for it. Canestrini mentions that the drivers were shouting and making gestures at each other, but neither one was slowing down and neither were they paying any attention to his futile efforts to get them to slow down. They entered the last lap almost deal even and stayed that way well into the lap.

On the last part of the last lap Nuvolari was almost literally side-by-side with Varzi. Going into the last turn before the finishing straight, however, the advantage lay with Varzi. His Bugatti could still both out-brake and out-accelerate the Nuvolari Alfa Romeo. And Varzi was using all the road and his Bugatti was as wide as he could make it. Despite the frantic efforts of Nuvolari to pass him before last turn, Varzi braked later into the corner and then rushed away from Nuvolari, using the slipstream to assist him over the last few hundred meters. At the finish line Varzi was a scant 0.2 seconds ahead of the Flying Mantuan after Nuvolari's heroic effort to catch the Bugatti simply fell short. Had there been a 31st lap, the finish could have easily been reversed.

In his book, Moretti has Nuvolari in a "crisis of conscience" lifting his foot and allowing Varzi by for the win. It seems difficult to accept this judgement. As even Canestrini points out, Varzi and Nuvolari were racing and ignoring any outside influences to moderate their speed and keep in mind the "deal" that had been made. The two drivers had engaged in a series of close battles on the track over the past several seasons and while apparently were civil to each off the track, they went at it hammer and tongs while on the track. Keep in mind that it did not matter financially who won, only that one or the other did indeed win the event. While Varzi may have won, it was not a gift from Nuvolari.

Birkin was to die on 22 June 1933, from what most initially thought was as the result from the burn he received. Apparently the Englishman neglected to have the burn attended to or it was later to become infected for another reason. In June, Birkin was hospitalized with his health in serious danger. Although most accounts attribute his subsequent death solely to his burn turning septic, there is reason to believe that while perhaps it played a role, the real killer was something else. During the Great War, Birkin served in the Middle East and fell ill as did many others with malaria. It is now thought that Birkin suffered a relapse of the disease and in a weakened condition from the apparently untreated burn, died. Had he not suffered the burn, or had it been properly attended to, it is thought that he could have survived the relapse and returned to racing. It must be noted that while the burn may have played a role, Birkin may have been in danger regardless.

While there was much grumbling and grousing by the other drivers and ticket-holders, "The Six" and Canestrini had acted within the rules as well as the law. Even Lurani makes that point very clear. All those in the syndicate made a tidy profit from the affair and got on with life. Within a few months the storm and the clouds that hung over the actions of the syndicate dissipated. One factor was the death of both Borzacchini whose joy at the financial windfall was "a pleasure to witness" according to Lurani and Campari at Monza that Fall. Another factor was that the Fascist government silenced criticism of the plan and quietly took steps to ensure that there would not be a repeat of 1933.

When the next Corsa dei Milioni was run in 1934, Marshal Italo Balbo was the Governor of Libya. And he did make one small change in the procures of when the tickets from the lottery were drawn: 30 minutes prior to the start when the cars were on the grid and the race was about to start. Sforzini suffered at the hands of critics about what had happened. In 1936, he was replaced as President of the Automobile Club del Tripoli by Ottorino Giannantonio. Sforzini was then forced to return to Italy and allowed to fade into obscurity. He was forgotten by those within the racing community with one exception: Canestrini. After his death in February 1956, Canestrini still editor at La Gazzetta dello Sport years later published an obituary for his friend Sforzini.

This article had its origin in an earlier Rear View Mirror. The column was entitled "The Corsa dei Milioni, the 1933 Gran Premio di Tripoli the Race that was Rigged?" and appeared in August 1999. I just wanted to get it "right."

However, the real origin lies with Betty Sheldon as the result of her examination of the Tripoli race in Volume 3: 1932 1936, A Record of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing.

Giovanni Canestrini, Uomini e Motori

Phil McCray and Mark Steigerwald of The International Motor Racing Research Center at Watkins Glen for their help and assistance.

Alessandro Silva for his invaluable assistance and help with the translations.

The past is what you remember, imagine you remember, convince yourself you remember, or pretend to remember. Harold Pinter

The real story starts with the Italian colony of Libya or Tripolitania in North Africa. It is looking for sources of income to offset the balance of payments from Rome. Likewise, the Fascist government is also looking for ways to promote the colony. It is looking for ways to entice people to visit and then the hope was settle in Libya. Tourists are not being attracted in numbers as large as desired, much less immigrants. So far, the results have not been encouraging.

The real story starts with the Italian colony of Libya or Tripolitania in North Africa. It is looking for sources of income to offset the balance of payments from Rome. Likewise, the Fascist government is also looking for ways to promote the colony. It is looking for ways to entice people to visit and then the hope was settle in Libya. Tourists are not being attracted in numbers as large as desired, much less immigrants. So far, the results have not been encouraging.

Canestrini is strangely quiet about any remuneration he may have received as a result of his role in this affair. While it is never clearly stated, apparently Canestrini did not do this solely out of his love of sport. Moretti quotes Lurani mentioning that one or all of the trustees presenting a Fiat Balilla to Canestrini as a token of their gratitude.

Canestrini is strangely quiet about any remuneration he may have received as a result of his role in this affair. While it is never clearly stated, apparently Canestrini did not do this solely out of his love of sport. Moretti quotes Lurani mentioning that one or all of the trustees presenting a Fiat Balilla to Canestrini as a token of their gratitude.

Acknowledgements

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 7, Issue 29

Atlas F1 Exclusive

Interview with Button

Tales from the Thirties: Tripoli, 1933

British GP Review

The British GP Review

Reflections from Silverstone

The Final Straw

Columns

Season Strokes - the GP Cartoon

Qualifying Differentials

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |