|

|||

|

| |||

Rear View Mirror Rear View MirrorBackward glances at racing history | |||

| by Don Capps, U.S.A. | |||

|

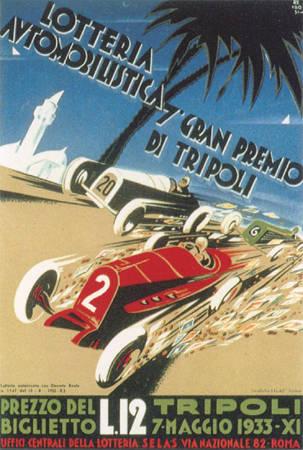

Setting The Record Straight: The Corsa dei Milioni, the 1933 Gran Premio di Tripoli - the Race that was Rigged?

However, for the sake of those who are too lazy to read the entire chapter (shame on you!), here's a Readers Digest version of Neubauer's account:

Marshal Italo Balbo, governor of Tripoli, opens a new racing circuit. To spark interest in the race, a lottery is organized. The 11 lira tickets are very popular and sell well throughout Italy. Drawing of the tickets takes place three days before the event for the holders of the 30 lucky tickets, one of each starter in the race. Winning ticket is worth 7,500,000 lire. So much for the Neubauer version. Well, his account of the 1933 Gran Premio di Tripoli is accurate in several instances: it did take place in 1933 at the Mellaha circuit outside Tripoli; it was won by Achille Varzi; Tazio Nuvolari was second; there was a lottery connected to the race results; the unfortunate Sir Henry Birkin did die several weeks after the race; and, there was some sort of collusion as to the outcome of the race.

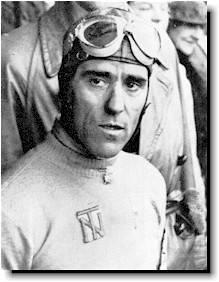

Now to try to separate Myth, Legend, and Truth from each other: On May 7th, 1933, the 30 starters of the VII Gran Premio di Tripoli sat on the grid of the Mellaha circuit just outside the city and waited to start the first of the race's 30 laps around the 13.1 kilometer circuit, a distance of 393 kilometers. The outcome of the Corsa dei Milioni and the Lotteria dei Milioni were going to be decided after - well, being decided. The grid, as was the norm for that time, was determined by drawing ballots and the race numbers applied accordingly - even numbers starting from the pole, # 2 all the way back to the last on the grid, # 60. Luigi Premoli in PBM-Maserati was on the pole with the Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 of the great Tazio Nuvolari next to him on the first row of the grid. The field was arranged in row of four. Achille Varzi was on the outside of row two in a works (Automobiles Ettore Bugatti) Bugatti 51. And on the fourth row of the grid was Baconin Borzacchini in another Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo. At the start, Carlo Gazzabini, on the second row next to Sir Henry (Tim) Birkin, Maserati 8C-3000, took off like a rocket in his Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 grabbing the immediate lead. However, as the field came around to complete its first lap, Birkin was leading the race. Birkin was followed by Nuvolari, Giuseppe Campari (works Maserati 8C-3000), Goffredo Zehender (Raymond Sommer-entered Maserati 8CM) who started from the fifth row, pole-sitter Premoli, and the rest of the pack. When the field came round the next time, it was led by Campari who passed both Nuvolari and Birkin and was starting to already draw out a cushion. On this lap Luigi Fagioli peeled off and pitted his Maserati 8CM for a plug change. Just short of the halfway point, 14 laps, Campari pitted - his oil tank coming adrift and causing problems with lubricating the engine. After several quick, frantic attempts to bolt it in place, the offending tank was secured in place with a rope found in the pits. However, after several more laps Campari was forced back into the pits to retire. Yet another attempt to make further repairs was halted once it became apparent that the lack of oil had produced a death rattle in the engine of the Maserati. On the same lap that Campari originally pitted, so had Birkin - pitting his Maserati to refuel. The stop was utterly routine, the only drama being Birkin accidentally getting a burn on his arm from the exhaust pipe, an all too common occurrence and an occupational hazard in those days. Birkin was to die on June 22nd, 1933, from what most initially thought was as the result of the burn he received.

Nuvolari screamed out of the pits after Varzi. Over the last several laps of the race Nuvolari carved big chunks of time off the lead Varzi had built up. On the last part of the last lap Nuvolari was almost literally side-by-side with Varzi. Going into the last turn before the finishing straight, however, the advantage lay with Varzi. His Bugatti could still both out-brake and out-accelerate the Nuvolari Alfa Romeo. And Varzi was using all the road and his Bugatti was as wide as he could make it. Despite the frantic efforts of Nuvolari to pass him before last turn, Varzi braked later into the corner and then rushed away from Nuvolari. At the finish line Varzi was a scant 0.2 seconds ahead of the Flying Mantuan after Nuvolari's heroic effort to catch the Bugatti simply fell short. Had there been a 31st lap, the finish could have easily been reversed.

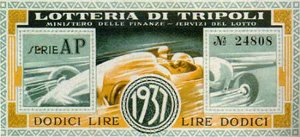

But what about Louis Chiron? Sorry, he wasn't even there! What about Borzacchini and the oil drums? The Alfa he drove retired with transmission problems, not from contact with any of the scenery, particularly oil drums. What about Marshal Italo Balbo? He didn't become the Governor of Tripoli until the Spring of 1934, almost a year after the race. And didn't Tim Birkin die on 22 June 1933 of septicemia as a result the burns he received during his pit stop? True, that is the date Birkin died, but it is now thought that the actual cause of his death was from recurrent malaria, a result of his service during the Great War. But what about The Fix? There was one, wasn't there? Yes, there was an agreement about the finish, but hardly the sort of affair that Herr Neubauer dreamed up. In fact, the truth is maybe more interesting in many ways than the myth! It is very possible that the entire truth may never be known. What follows is based on the best information available. Between Betty Sheldon * and Valerio Moretti's 'When Nuvolari Raced', this is what appears to be as close to the truth as I can get: The story starts with the Italian colony of Libya in North Africa. It is looking for sources of income to offset the balance of payments from Rome. Tourists are not being attracted in as large a numbers as desired, much less immigrants. The Italian government is looking for ways to entice people to visit and then settle in Libya. So far, the results have not been encouraging. With motor racing a popular sport among Italians, a new racing circuit is constructed outside the capital of Libya, Tripoli. It is completed in the latter part of 1932 and is scheduled to be a part of the series of races held in on the Southern side of the Mediterranean the following Spring. Meanwhile, an Italian journalist is musing on both the new Mellaha circuit and the Irish Sweepstakes. Rather than a lottery based on selling chances to be selected as the holder of the ticket for the winning horse in the Sweepstakes and win the jackpot, Giovanni Cantestrini thought the same scheme could be applied to a motor race. The president of the local auto club in Tripoli, Edifio Sforzini, was approached by Cantestrini with the scheme for a sweepstakes in conjunction with the race in the Spring.

The "Lotteri dei Milioni" and the "Corsa dei Milioni" were off and, well, running. The first lottery tickets went on sale in October 1932 and the last date for selling the tickets was on April 16th, 1933. It is unclear exactly how much the lottery raised or what the value of the winning ticket was - pick a number, three million or 7.5 million or eight million lira. Whatever the amount was, it was a huge amount of money for the time in Italy. And, the prize money for the race was very, very generous. In most cases the prize money for a race was quite small, usually being paid only for the top several positions, while the "real" money being paid out was the start or appearance money. In this case, the prize money was enough to guarantee that there was some very serious money to be made by finishing well in the "Corsa dei Milioni." Needless to say, nearly all the top teams, especially the Italian ones, were there. The lottery tickets were sent to Tripoli for the drawing several days after the last ticket was sold. The drawing was held on April 29th, 1933. It was supervised by the new governor, Pietro Badoglio. Each of the 30 entrants in the race had a ticket drawn and assigned to that entry for the race. This was a Saturday and the day prior to the running of the Gran Premio di Alessandria. It was eight days prior to the race. It was sufficient time to ponder the wealth that awaited the winner of the lottery. It was also plenty of time to seriously consider means to narrow the odds. Now we get to the "good" part and here you find that when money talks, nobody walks. In an account recorded by Aldo Santini in his biography of Nuvolari, Santini used notes taken from his interviews with Varzi to reconstruct the events surrounding the Tripoli race. Since Varzi had nothing to gain from being untruthful, there is a strong tendency to that him at his word. At some point on the same day of the drawing, Nuvolari contacted Giovanni Cantestrini about a meeting. Both were in Alessandria for the Gran Premio. A meeting was held with Cantestrini, but also present were Varzi and Borzacchini. Cantestrini later claimed the topic of the meeting was the discussion of travel plans to the Tripoli race the following weekend. However, Varzi said that the only topic discussed was the lottery and the race. Also present were the ticket holders of the Nuvolari, Varzi, and Borzacchini entries in the race! And a lawyer as well. The host was Ettore Bettoia who supplied the hotel room for the meeting. Moretti gives the name of the holder of the ticket for Nuvolari as Alberto Donati, the town clerk for Cellino Attanasio, which is near Teramo (if that helps). The man who drew the ticket for Varzi is usually given as Enrico Rivio from Pisa, while others say that he was a timber merchant from Castenuovo Berardenga, Siena, and neither Sheldon nor Moretti mention this person by name. The person with Borzacchini's ticket was Alessandro Rosina from Piacenza. To the best of our knowledge, the meeting took place on either Sunday or, more likely, Monday following the race at Alessandria. As Varzi recounted, the meeting was held to discuss the very specific topic of "how to find a formula which did not contravene the sporting rules," to divide the lottery money among what became known as The Six. This was scarcely a secret meeting. The May 15th, 1933, issue of Moteri, Aero, Cicli e Sport reported not only that the meeting had taken place, but that someone had approached Piero Ghersi with an offer of one million lire if he won the race. Others have Tim Birkin being offered either 70,000 or 100,000 lira by his ticket holder if he won the race.

The important outcome of the meeting was that there was to be no pre-arrangement as to the outcome of the race. There was no flipping of a coin or any discussion about who should win. What was decided was that regardless of whether Nuvolari, Varzi or Borzacchini won the race, the jackpot was to be split evenly among The Six. And the drivers got all the prize money on top of that. Even before the meeting the sporting papers were printing reports - which were nearly identical in content - about the purpose and probable outcome of the meeting. That is all except one, La Gazzetta dallo Sport. And the absence of such reports was remarkable, since its motor sports editor was none other than - guess who? - Giovanni Cantestrini! Indeed, La Gazzetta alone among the sporting journals of the day is strangely quiet about the entire affair. One can't help but wonder why... The report in the May 14th, 1933, issue of R.A.C.I. by Raffaello Guzman goes to some lengths to make it clear that the Varzi-Nuvolari battle for the win was the Real McCoy. The May 20th, 1933, issue of Auto Italiana also went to great lengths to explain that Varzi and Nuvolari put on a real hammer-and-tongs, no quarter battle for the win. And it makes specific mention of the pact and that pact or no pact, Nuvolari wanted to win and so did Varzi. Even Motor Sport for June 1933, mentions the agreement between the drivers and states that this had no effect on the outcome of who won. None of that falling in line and creeping across the line nonsense that Neubauer mentions. With such widespread knowledge of the agreement made by The Six, there was certain to be some mumbling and grumbling. There was a quiet inquiry made, but The Six were never brought to trial since they were never charged with anything! The "crime" was more one of, as Betty Sheldon correctly expresses it, "moral dimensions" than of a criminal nature. And as if that wasn't enough, there was the implicit support of the state for those involved. After all, Nuvolari and Varzi were public heroes and the Fascist government was not going to allow the drivers to be subject to any charges since, technically, there was no intent to defraud or "cheat" according to the rules of the contest. When the next "Corsa dei Milioni" was run in 1934, Marshal Italo Balbo was the Governor of Tripoli. And he did make one small change in the procures of when the tickets from the lottery were drawn: when the cars were on the grid and the race was about to start.

|

| Don Capps | © 1999 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: capps@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |