Atlas F1 Senior Writer

Paul Morgan was not the more public face of Ilmor Engineering. But without his skills and talents the company which provides engines to the McLaren team would not be what it is today. Karl Ludvigsen writes about his close friend, who was killed in an airplane accident last Saturday.

Later I came to know how and why Paul Morgan became so knowledgeable. He was born in 1948 into a family passionate about cars. His father, Brian Morgan, was managing director of an automotive components producer, Benton & Stone, known by the brand name 'Enots'. For recreation Brian Morgan restored cars. Inevitably Paul was dragooned into assisting in the well-equipped Morgan workshop at the family home at Handsworth Wood in Birmingham. At the age of 15 his attention was focused by a gift from his father: a 1904 De Dion-Bouton automobile. But the gift had a catch: Paul had to rebuild it. "That was one of his best ideas," said Paul. "It got me using lathes and milling machines and finding out what works and what doesn't."

Next, of course, the De Dion had to be entered in the London-Brighton run. Young Paul Morgan was refused an entry, however. He was still a learner-driver! As soon as he was eligible he entered and the De Dion has been a steady runner ever since. Paul and the French auto never failed to complete the drive to Brighton.

Paul's next personal project was the rebuilding of a twin-cylinder Vincent Black Shadow motorcycle. This got him thinking about a car that might be raced. After considering an Amilcar he plumped for an £80 investment in a Lagonda Rapier, its 1,100 cc twin-cam engine famously amenable to hotting-up. Bodying the Rapier as a single-seater, Paul took no half-measures with its engine. No fewer than three Roots blowers belt-driven from the back of the engine were piped to give two stages of supercharging. This gave way to a less-elaborate two-stage system that still gave a boost of 22 p.s.i. and propelled Paul and his Rapier Special to serious hillclimb and sprint successes.

Meanwhile Paul Morgan had found gainful employment. At the beginning of 1970, after passing out of Aston with a BSc degree in mechanical engineering, he decided he'd better look around for a job. "Some sort of engineering work," he thought. Perusing the latest Motor Sport he saw an article on Cosworth, then making its mark in several classes of racing from Formula One on down. "That would be interesting for a year or two," mused Morgan. Paul's letter of enquiry was met by Keith Duckworth's response of February 3rd, 1970 suggesting an interview. But the Cosworth gears ground slowly. Eventually he faced and passed a three-hour interview, recalled as an "inquisition", by engine-design genius Duckworth. Paul Morgan was hired at the beginning of August 1970.

One of his earliest jobs there was to set up an in-house piston-making department, a new initiative for Cosworth. Paul specified, bought and modified the machine tools needed to make the company self-sufficient in the machining of pistons. This has since become an important profit centre for the company. Back in engine development, Paul worked on the GA V-6, a 24-valve racing engine based on the rugged Ford Essex cylinder block. It was successful in the 1970s racing Capris, especially in Germany.

Paul Morgan next found himself on terra that was incognita even to Cosworth: the development of a water-cooled vertical-twin-cylinder racing engine subsidised by Norton Motorcycles. "When you go into a different field," reflected Morgan later, "you may not deal well with all elements of a project." It was not one of Cosworth's great successes. Twenty-five sets of parts were laid down for the 750 cc Norton twin, of which great things were expected. However, it was not to be. Paul accompanied Keith Duckworth to the meeting at Thruxton Circuit with Dennis Poore, head of Norton, at which they decided to suspend the project because it wasn't showing signs of working out.

Eventually turning to the Cosworths, the Vel's Parnelli team fitted Hilborn fuel injection and a turbo-blower and found that the V-8 responded well. In fact they raced one in the last event of 1975, Phoenix, where it finished fifth. Others jumped on the cut-down Cosworth bandwagon. Paul Morgan was appointed to look after the necessary engineering at Cosworth while an American, Larry Slutter, operated in the field at all the IndyCar races. Morgan and Slutter teamed up to create a business within a business, generating fresh demand for Cosworth engines from the IndyCar community.

The new V-8 became the Cosworth DFX, which was to dominate IndyCar racing for almost a decade. As early as 1977 the Penske version of the DFX helped Tom Sneva to an IndyCar championship in a season when the engine won eight races. It would win 82 consecutive IndyCar races before its reign would be ended in 1987 by the Chevrolet Indy engine that Morgan would make in Northamptonshire with Mario Illien.

Paul's experience as project engineer with these turbocharged engines made him the ideal man to take charge of a pet Duckworth scheme - "a bit of a hobby, really" - to power an unlimited tunnel-hull hydroplane with a pair of water-borne DFXs. The power was there, some 850 bhp per engine, as was the speed: they measured a maximum of 176 mph (281 km/h). But getting up to speed was not easy. "We had no boost to speak of at 2,000 rpm," said Paul, "so we couldn't get the boat up on the step. We finally had to inject nitrous oxide to do it." It was an interesting engineering exercise but not another business for Cosworth.

Paul Morgan, concentrating on the IndyCar engine program, was frustrated: "We had a list of 21 things that we felt needed doing on our Indy engines. We couldn't get Keith to agree to our doing any of them." Morgan had something of his own in view: "I'd always had an idea that I'd like to run my own business. My father was always in charge and I thought I'd like to do that. I was 35 years old, about right to have the energy to set up the business." But another idea presented itself in one of the test cells at Cosworth in the summer of 1983 in the person of Swiss engineer Mario Illien who took Paul aside and confided, "I think I have to go." Loyal though he felt to Duckworth, who had given him his big chance, Illien also realised that it was time to look after his own interests.

"We didn't have much contact at work," said Illien of Morgan, "but quite early on he invited me for a Sunday lunch with his family." Serious and obviously intelligent, obsessed with cars and racing, Illien made a good impression on Morgan. The two men shared an approach to cars, racing and technology of all kinds that was both practical and intellectual, a rare and sympathetic combination. Before launching Ilmor Engineering they explored and conformed this compatibility with several extracurricular engineering projects.

Ilmor was founded in 1984 on a very simple principle. As Paul explained it to me, "I see my job as providing everything that Mario needs to make his engines." Their complementarity was commented on by the lawyer who forged the deal that saw American entrepreneur Roger Penske invest in their start-up company: "Paul represented ultimately English qualities like diligence, concentration, organisation, high intelligence, seriousness and focus. Mario was more of a gifted artist, like Picasso. The two together complement each other."

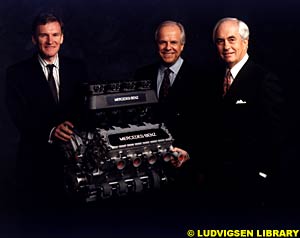

The achievements of their creation, Ilmor, have passed into legend. Ilmor's Chevrolets won every Indy 500 from 1988 through 1993 and their pushrod Mercedes-Benz V-8 was the 1994 winner. They won CART championships for Chevrolet and again in 1997 for Mercedes-Benz. After entering Formula One with Leyton House, Pacific and Sauber, Ilmor became part of the Mercedes-Benz family in 1994. Hard work by both Ilmor and McLaren - not to mention Mika Hakkinen - brought the Formula One Championships of 1998 and 1999.

A sense of the philosophy of Morgan and Illien was given by a quote from Paul: "Our company starts with a great advantage. Unlike many others divided into 'Chiefs and Indians', we are all 'Indians'. Our history, the nature of the work and the enthusiasm of our team - all combine to make us an effective engineering project unit." Both men tried hard not to let Ilmor get too big in terms of its employee numbers. They also fought shy of any formal organisational structure to ensure that everyone saw themselves as equals. Eventually they had to give way on both points - but not too much.

Although it had its struggles, Ilmor developed into a highly successful business. This allowed Paul to indulge his passion for aviation. He was justifiably proud of his planes kept at Sywell Aerodrome, not far from Brixworth. They included an De Havilland Chipmunk, a North American A76 Harvard and a P51D Mustang with Rolls-Royce power. The cam grinders at Ilmor had been specified with a span big enough to cope with Merlin camshafts; many flying Merlins owe their camshafts to Ilmor. Paul's spare Merlin V-12 was kept in one of the living rooms of his house in Brixworth, The Brown House. Its stables housed his vintage cars.

Paul's newest acquisition had been a Hawker Sea Fury. When I spoke to him recently he was very excited about it. He died on the scene of a crash when landing his Sea Fury at Sywell at around 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, May 12th. David Coulthard dedicated his victory in Austria on the following day to Morgan, and refrained from champagne-spraying as a sign of respect - a thoughtful gesture. Although he was not the more public face of Ilmor, without Paul's skills and talents the company would not be what it is today. My deepest sympathies go to his wife Liz, their children Patrick and Lucy, his colleagues and all his many friends.

When the call came from Chevrolet, I knew the job would be pleasant as well as easy. It was 1984, and Chevrolet needed somebody to visit this new little engine outfit in England named Ilmor and describe what they were doing. I was confident that the job would go smoothly because I already knew one of the partners in the new outfit, Paul Morgan. Ten years later, Paul asked me to write the history of Ilmor's first ten years. This I did with great pleasure.

I'd first met Paul in 1980 when I was running Ford's European motor sports activities. He was busy in the back room at Cosworth where they carried out their exotic future developments. As a colleague put it, "Paul was going around and organising all these people, six different people being fired up, keeping them all going." We shared an interest in unusual cars and I was aware that he had lots of vintage-car know-how. Thus he was the first person I thought of when I had a problem with the restoration of my Moretti. He helped me get con rods and a new crankshaft made for this rare Italian car.

I'd first met Paul in 1980 when I was running Ford's European motor sports activities. He was busy in the back room at Cosworth where they carried out their exotic future developments. As a colleague put it, "Paul was going around and organising all these people, six different people being fired up, keeping them all going." We shared an interest in unusual cars and I was aware that he had lots of vintage-car know-how. Thus he was the first person I thought of when I had a problem with the restoration of my Moretti. He helped me get con rods and a new crankshaft made for this rare Italian car.

Paul Morgan started competing with the Rapier in the late 1960s when he was at Aston University in Birmingham. His last race with the famously-noisy light-blue car was at Cadwell Park in 1977. Light blue was also the right colour for another Morgan acquisition, a French Talbot-Lago racing car. Paul bought his beautiful and unique single-seater Talbot-Lago Grand Prix car as a semi-basket case in 1972 and by 1976, after fitting hydraulic brakes, he was racing it actively. Efforts over the years to enlarge its engine to 4.3 litres had taken their toll, however. When the cylinder block expanded beyond salvageability Paul decided to make a new one: "Wonderful challenge for an engine man!" With a new block welded of sheet steel Paul was racing the big blue car again by the early 1980s.

Paul Morgan started competing with the Rapier in the late 1960s when he was at Aston University in Birmingham. His last race with the famously-noisy light-blue car was at Cadwell Park in 1977. Light blue was also the right colour for another Morgan acquisition, a French Talbot-Lago racing car. Paul bought his beautiful and unique single-seater Talbot-Lago Grand Prix car as a semi-basket case in 1972 and by 1976, after fitting hydraulic brakes, he was racing it actively. Efforts over the years to enlarge its engine to 4.3 litres had taken their toll, however. When the cylinder block expanded beyond salvageability Paul decided to make a new one: "Wonderful challenge for an engine man!" With a new block welded of sheet steel Paul was racing the big blue car again by the early 1980s.

In 1974 another customer made an unusual request of Cosworth. American Roger Penske, then active in both Formula One and IndyCar racing, ordered five DFV V-8s but specified some changes. He required no fuel systems and asked for the displacement to be reduced from 3.0 to 2.65 liters, the engine size needed for the turbocharged IndyCar racing which Penske clearly intended. But he changed his mind and Cosworth sold the embryo engines to the Vel's Parnelli team, co-owned by Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones. "They let them languish for a while," Morgan recalled.

In 1974 another customer made an unusual request of Cosworth. American Roger Penske, then active in both Formula One and IndyCar racing, ordered five DFV V-8s but specified some changes. He required no fuel systems and asked for the displacement to be reduced from 3.0 to 2.65 liters, the engine size needed for the turbocharged IndyCar racing which Penske clearly intended. But he changed his mind and Cosworth sold the embryo engines to the Vel's Parnelli team, co-owned by Vel Miletich and Parnelli Jones. "They let them languish for a while," Morgan recalled.

Throughout these years "Picasso" Illien could concentrate on design and development, knowing that Paul Morgan was taking care of the plant. Paul was never happier than when showing me some new machines he had acquired to make parts faster and better. A major aim at Ilmor was and is to ensure quality by making more of the engine in-house. It was Paul's job to achieve that, and he was good at it. From its first square building, Ilmor in Brixworth, Northamptonshire has expanded into a well-coordinated complex under Paul's personal supervision.

Throughout these years "Picasso" Illien could concentrate on design and development, knowing that Paul Morgan was taking care of the plant. Paul was never happier than when showing me some new machines he had acquired to make parts faster and better. A major aim at Ilmor was and is to ensure quality by making more of the engine in-house. It was Paul's job to achieve that, and he was good at it. From its first square building, Ilmor in Brixworth, Northamptonshire has expanded into a well-coordinated complex under Paul's personal supervision.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 7, Issue 20

Atlas F1 Special

Interview with Ralf

The Man who Powered Ilmor

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Spanish GP Review

The Austrian GP Review

Reflections from A1-Ring

Battle Lines

Farewall Austria

Columns

Qualifying Differentials

Season Strokes - the GP Cartoon

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |