BusinessF1 Editor in Chief

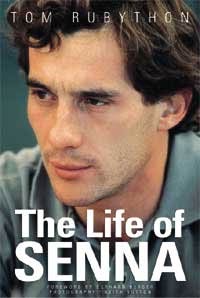

After years of research and numerous interviews, Tom Rubython releases the definitive biography on Ayrton Senna: The Life of Senna. With photos by Keith Sutton and a foreward by Gerhard Berger, this book is an essential reading for any motorsport fan. Atlas F1 presents the 17th chapter of the book: the Feud with Prost

The Lotus years were quiet ones and the feud did not build up until Senna replaced Stefan Johansson as Prost's team-mate in 1988. Prost had been used to running with inferior number-two drivers and Rosberg openly admitted he could not get near him. When Senna finally arrived after Rosberg retired, the Finn did not expect him to bother Prost. Rosberg was absolutely stunned when Senna was faster. And so was Prost.

When the animosity developed, Prost was supposed to fit into the 'decent bloke' category, and journalists assumed Senna was at fault. Typically, Senna's side of the story was always different: "I have worked with Gerhard Berger, Michael Andretti, Elio de Angelis, Johnny Dumfries, Satoru Nakajima and Alain Prost, so I think it is necessary for everybody who looks into this particular matter to consider the reality: as far as team-mates are concerned, I have always got on very well with all of them except one. The only driver I have ever had problems with as a team-mate is Prost."

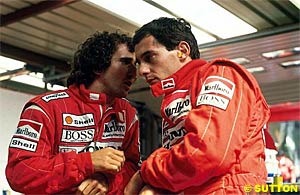

The chemistry between Senna and Prost was a volatile brew of contradictions, and melding their characters into a productive force was a delicate business – as McLaren team principal Ron Dennis discovered. He says handling Senna and Prost required a combination of disciplines ranging from ego manager to tightrope walker, juggler to marriage counsellor. As he explains: "The relationship between any two human beings is a very complicated thing, like in a marriage, and the drivers' relationship is very, very complicated. But the negative aspects of having two such drivers can be turned to produce a motivating force. However, as in any finely-tuned situation, you walk a tightrope between falling off into failure and successfully getting to the other side.

"The challenge was to try to understand their negative differences, try to isolate them, then turn them into positives. I'm not a marriage counsellor but I think guidance and support are the words to use when it comes to handling drivers. I had to support and guide them through racing problems and human problems."

The conflict was perhaps inevitable, and their feud continued far beyond their tenure as team-mates. The tension between Senna and Prost initially stemmed from real, or imagined, preferential treatment of one driver over another. In 1988 when Senna joined McLaren, where Prost had ruled for four years, it was obvious that Senna was the faster driver, but less obvious that he was the better driver.

The slower driver needed to salvage his bruised ego and began to find fault with his equipment. McLaren provided both drivers with identical cars but when Senna became faster, Prost began insinuating that Honda was giving the Brazilian better engines. By the time Prost left McLaren, because of the personality clash with his team-mate, he was openly accusing the team of favouring Senna – and perhaps he was right.

Prior to their coming together at McLaren, Prost had won 26 races and claimed the 1985 and 1986 driving titles with the team. Senna, five years younger than Prost, had won six races with Lotus and was obviously destined for greatness.

Both men hated to lose. As Keke Rosberg once famously said: "Show me a good loser and I'll show you a loser – period." And since each man's team-mate represented an impediment to winning – or, worse still, had the potential to turn the other into a loser – it was vital for both Prost and Senna to take immediate steps to gain the upper hand at McLaren.

From a cautious mutual respect in its early stages, the relationship between Prost and Senna rapidly deteriorated into a mutual dislike that ultimately became what can only be called silent hatred. As Senna explained himself: "On the path to the summit, there isn't room for two." Prost said: "Nothing else was important. He just wanted to beat me and to beat me in a bad way sometimes. When I thought I was committed 100 per cent or just 99 per cent to Formula One, because the one per cent missing was maybe my family or my children, a different way of life, you know he was committed 110 per cent."

In 1988 the two were interviewed together in the McLaren motorhome and asked which of them would win the championship. Prost said: "Can we be equal?" Senna replied: "No there can only be one winner." Prost thought it was all very funny but Senna took it deadly seriously.

The war started, and came to a serious head at the 13th round, the Portuguese Grand Prix. Senna seemed to swerve deliberately in front of Prost, squeezing him so close to the Estoril pitwall that several signalling crews ducked for cover. Prost, who had been leading Senna at the time, and in fact went on to win, was livid.

Even Ron Dennis could not fix this one: from then on it was open warfare. Dennis tried by constantly throwing the two men together. For instance, he made them travel in the same helicopter to races. It had no effect and they did not talk to each other, merely stepping from the helicopter stony-faced and walking apart, to the bemusement of onlookers.

Senna ultimately won the 1988 world crown and Prost was second: as McLaren partners in 1988, they garnered a total of 15 victories. But Prost's belief that his Brazilian team-mate was a dangerously disturbed madman grew when Senna revealed that he had found religion. When Senna announced that he believed in God, the press ridiculed him and Prost used it against him. "Ayrton has a small problem," he said. "He thinks he can't kill himself because he believes in God, and I think that's very dangerous for the other drivers."

Journalists, sensing a colourful story, reported that Senna thought he was invincible because God was his co-pilot. "It's unreal to say those things," Senna responded angrily. "Of course I can get hurt or killed in a racing car, as anybody can, and this feeling, this knowledge, is absolutely necessary for self-preservation."

After the Imola race, Senna and Prost traded what Japanese newspapers cutely called 'honour-injuring remarks'.

Senna won the race but Ron Dennis made him apologise to Prost. Senna admitted: "At that moment, the emotion made me cry. I said sorry, but I thought it was unfair. The world of Formula One has bent me like no person ever could for the rest of my life."

The war lasted six years, with constant sniping to favoured journalists. Senna said once: "Prost is a coward." Prost responded: "He takes himself for a mystic, he thinks that nothing can happen to him. That he's invulnerable. It's a philosophy that puts the other drivers in jeopardy."

Although Prost let Senna by on that occasion, his open-door policy was definitely not in effect in the championship-deciding Japanese Grand Prix.

Prost set the stage for the events in the race, saying: "A lot of times last year and this, I opened the door and if I did not open the door we would have crashed. This time I will not open the door."

Prost had the advantage because if both went out he would be crowned world champion. Senna, for all his intelligence, seemed not to have grasped this simple fact. When the two McLarens collided at the Suzuka chicane, Prost walked away from his car (which was later found to be undamaged) and although Senna recovered and went on to win the race, he was later disqualified (for missing part of the circuit) and Prost was declared world champion.

It happened the next year, too, and again at Suzuka where Prost, by then with Ferrari, once more closed the door on Senna and the Brazilian again used his McLaren as a battering ram to open it. The incident, in the first corner on the first lap, put both the McLaren and the Ferrari out of the Japanese Grand Prix but Senna's lead over Prost in the standings meant the 1990 championship went to the Brazilian. "I am at peace with myself," he said afterwards, while the incensed Prost insisted his actions were 'deliberate, unsporting and intimidating'.

Senna retorted: "I never caused the accident in Suzuka. It was never my responsibility and you should see that from the video, not my own words. The way the whole affair has been treated is like I have total responsibility. I was blamed for everything, I was treated like a criminal! So of course I thought about stopping. Many things have gone through my mind, but I am a professional, and the values I have in my life are stronger than to be influenced by other people."

British TV commentator Murray Walker, for one, didn't buy it: "There is no doubt at all that in 1990, if he did not drive into Prost, he had certainly made his mind up, as he subsequently admitted at that famous press conference. He had decided before the race, because in his view he was on the wrong side of the track. He believed that he should have been on the left-hand side, and because of the circumstances Prost was there. Senna bitterly resented that and said to himself before the race, as he subsequently admitted, 'I am going to go for it and if Prost turns in on me that's his hard luck'."

Senna was right. The truce did not last long but he had tried, as he said: "I always try not to criticise him, or react to criticism from him. That doesn't build anything, it is just destructive. What we have to be very aware of is words. We can build a lot, but we can also destroy a lot. I prefer to build than to destroy. So it is not necessary to go into details about any particular case or anything. It is just my philosophy of how to behave."

A year later, after he had won the 1991 world championship, Senna gave his version of what had happened the year before at Suzuka. "It was a sad championship, but that was a result of the 1989 championship. Remember, I won that race and it was taken away. I was so frustrated that I promised myself that I would go for it in the first corner. Regardless of the consequences, I would go for it. He [Senna by this time never used Prost's name] just had to let me through. I didn't care if we crashed. He took a chance, he turned, and we crashed. But what happened was a result of 1989. It was built up. It was unavoidable. It had to happen. I did contribute to it, yes. But it was not my responsibility."

There was more trouble in the German Grand Prix in 1991. Prost poured all his venom out on Senna in a television interview, in which he accused him of deliberately weaving and brake-testing him. After the German Grand Prix, Prost made one of the most dangerous statements any Formula One driver has ever made: "He drove across me, braking in a strange way and weaving. If I find him doing the same thing again I will push him off, that's for sure."

The inflammatory remarks later resulted in Prost being handed a suspended one-race ban. Senna took the threat calmly and spoke considerable truth when he said of his rival: "I think everybody knows Prost by now. He is always complaining about the car or the team or the circuit or the other drivers. It's never his fault."

Senna was dismissive of Prost's post-Hockenheim threat. He pointed to the fact that Patrese had got by him easily after two laps and was faster. He said Prost just could not get by: "We could have touched then at 300kph and if we had there would have been a big impact. He could have caused it. It was a desperate move by him."

Prost concluded by saying: "Now that my championship chances are over, I shall do my best to help Nigel and Williams Renault to win the title."

The precedent of a top driver refusing a team-mate was forgotten by the media after Senna moved to Team Lotus and in 1986 would not allow Derek Warwick to join the team. His reasoning was that Lotus was not up to the task of providing two equally competitive cars for two top drivers and the sport's insiders agreed with him. But the British media did not and since Warwick was a 'thoroughly decent bloke', Senna was called everything from a coward unwilling to face competition to a ruthless manipulator of other people's lives.

Mercifully, Prost and Senna eventually grew tired of fighting and after the Frenchman retired at the end of the 1993 season they finally shook hands and resolved to try and forget their differences.

The last time they met on the track was in the 1993 Australian Grand Prix at Adelaide. It was a momentous event for Prost who, with Williams, had already clinched his fourth world championship and made his decision to retire from the sport; and for Senna, who would the following year replace Prost at Williams after six seasons with McLaren.

At Adelaide Senna scored his 41st and last Formula One victory, a record second only to that of the man who stood beside him on the victory podium. Prost finished second in his final Grand Prix, thus retiring with 51 wins – the most successful of all Formula One drivers by that criterion. Then another kind of history was made as the two protagonists, who had dominated the sport for so long, gave in to their emotions. Their deeply-felt sense of occasion moved them to overcome their mutual animosity and stage a dramatic and emotional post-race reconciliation.

Prost extended a hand of friendship to Senna, a gesture that seemed to sweep away all those years of bitterness. A misty-eyed Senna hauled Prost up onto the top step of the podium to share the limelight, and embraced him warmly. Their peace pact was sealed with champagne, which they playfully showered over each other before discussing their feelings.

Senna was asked what he really thought of his rival now that their celebrated feud was relegated to racing history. "I think our attitude on the podium speaks for itself," he replied. "It reflected my feelings and, I believe, his feelings too."

And did Prost think they could ever become close friends? "I think only life will tell that. If you want to speak about the future you must also speak about the past and we don't want to do that. It's best that we remember only the good times we had."

Tragically, Senna's future was short-lived and few felt worse about that than Prost. Just prior to the ill-fated 1994 San Marino Grand Prix at Imola, Prost, who at the time was a member of the media, met Senna privately and they agreed to formally end their long-standing animosity. Prost recalled: "We had the warmest conversation I can ever remember. For the first time I felt he really wanted to be friends." Senna gave a message on live TV for the man he called a 'Formula One pensioner': "I miss you Alain". Two hours before he died, Ayrton said to the TV cameras: "Greetings to my friend Alain. I miss you, you know."

A few hours later, Alain Prost was one of millions of people who wept when Ayrton Senna was killed.

Senna once said: "All it takes to change people's view of a subject is to listen to the other side. Only then do you get the complete story." And now, as investigations proceed into the full extent of his remarkable life and achievements, Ayrton Senna is being praised more highly than he ever was when he was alive. When it is finally realised how truly extraordinary he was as a man and a driver, he will surely be accorded the full honour that sadly was missing during his lifetime. Perhaps this will be Senna's most important legacy to Formula One: by his remarkable example, to have created a greater awareness and understanding of genius so that it can be more easily recognised and appreciated, should anyone of such stature ever come along in the future of the sport.

Ron Dennis is sanguine about the feud as it fades in the memory. He says he learnt a lot from it. It was one of the main reasons why Dennis kept the reasonably amicable partnership between Mika Hakkinen and David Coulthard intact for so long – because of his experience with the most notorious of all team-mate feuds: the one between Senna and Prost.

History showed that Senna gave Prost full credit for his achievements. On television he was asked to rate the world's best-ever drivers. He rated Prost the third best: "I would say Fangio was number one. Unfortunately I come from a different time, so I didn't have a chance to see him really driving. For me he is the undisputed number one. In the 1980s and 1990s... Niki Lauda was another outstanding driver. And Alain Prost is the next one. The four championships he has achieved are real, they are reality. No one can dispute that."

It was probably Ayrton Senna's long-standing feud with Alain Prost that was most responsible for creating his negative image in the media. While Prost manipulated the media, Senna was constantly at war with it.

The feud started in a small way when Senna debuted in Formula One in 1984. That year the Monaco Grand Prix was held in the rain. Behind the wheel of his under-powered Toleman, Senna found himself in second place with the fastest car on the track. He was poised to overtake race leader Alain Prost in his McLaren when race director Jacky Ickx stopped the race and 'caused' Prost to win. Prost accidentally became Senna's bete noire.

The feud started in a small way when Senna debuted in Formula One in 1984. That year the Monaco Grand Prix was held in the rain. Behind the wheel of his under-powered Toleman, Senna found himself in second place with the fastest car on the track. He was poised to overtake race leader Alain Prost in his McLaren when race director Jacky Ickx stopped the race and 'caused' Prost to win. Prost accidentally became Senna's bete noire.

Soichiro Honda, the founder of the great car company, had developed a great relationship with Ayrton Senna from the days they had started working together in 1987 with Lotus. Senna was the first driver Honda was compatible with, and who gave the company the best and most reliable technical feedback. He was the driver who visited Honda in Japan and tended to its needs. The company had no relationship with Prost, who was not good at that sort of thing. In fact Prost's one big weakness was his inability to foster corporate relationships in the long term. So if there was a better engine Senna got it. After all, he had brought the fantastic Honda engine with him. The team was at its peak and, with equal equipment at their disposal and the freedom for each driver to use it to his best advantage, the stage was set for a major confrontation.

Soichiro Honda, the founder of the great car company, had developed a great relationship with Ayrton Senna from the days they had started working together in 1987 with Lotus. Senna was the first driver Honda was compatible with, and who gave the company the best and most reliable technical feedback. He was the driver who visited Honda in Japan and tended to its needs. The company had no relationship with Prost, who was not good at that sort of thing. In fact Prost's one big weakness was his inability to foster corporate relationships in the long term. So if there was a better engine Senna got it. After all, he had brought the fantastic Honda engine with him. The team was at its peak and, with equal equipment at their disposal and the freedom for each driver to use it to his best advantage, the stage was set for a major confrontation.

But 1988 was nothing compared to what was brewing for 1989. The season got off to a flying start at the San Marino Grand Prix when Senna, who went on to win the race, overtook Prost at the start. The disgusted Frenchman said the manoeuvre represented a sneaky breach of a previous agreement, instigated by Senna, that whoever was in the lead going into the first corner should be allowed to maintain it to avoid unnecessary risks. The basis of the first dispute was that Prost accused Senna of not respecting a 'non-aggression pact'.

But 1988 was nothing compared to what was brewing for 1989. The season got off to a flying start at the San Marino Grand Prix when Senna, who went on to win the race, overtook Prost at the start. The disgusted Frenchman said the manoeuvre represented a sneaky breach of a previous agreement, instigated by Senna, that whoever was in the lead going into the first corner should be allowed to maintain it to avoid unnecessary risks. The basis of the first dispute was that Prost accused Senna of not respecting a 'non-aggression pact'.

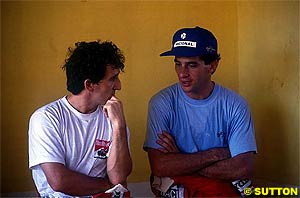

Occasionally the storm abated, and they would shake hands. Then it worsened still further. After the 1990 clash there was an attempt at reconciliation, as Senna said: "What happened between us in the past hasn't been in any way pleasant, either for us or for anybody else. It has been a bad time for everybody. I don't think we were ready to try to make friends a year ago. Now I have to try to believe that it will work. It may not work, because only time will tell: for him, for me, and so on. But you cannot say no, to yourself or anyone. You have to try under the conditions, under the circumstances. And I think we will try. We want to try and we will try. But only time will tell whether we can succeed."

Occasionally the storm abated, and they would shake hands. Then it worsened still further. After the 1990 clash there was an attempt at reconciliation, as Senna said: "What happened between us in the past hasn't been in any way pleasant, either for us or for anybody else. It has been a bad time for everybody. I don't think we were ready to try to make friends a year ago. Now I have to try to believe that it will work. It may not work, because only time will tell: for him, for me, and so on. But you cannot say no, to yourself or anyone. You have to try under the conditions, under the circumstances. And I think we will try. We want to try and we will try. But only time will tell whether we can succeed."

That was the end of the battles on the track. Prost retired for a season in 1992 and came back in 1993 with Williams. That started another off-track feud that simmered for two years during 1992 and 1993 over a drive at the dominant Williams Renault team. Senna basically wished to be Prost's team-mate in 1993 in the best car. Prost would have none of it – it was reportedly written into his contract that Senna could not be his team-mate.

That was the end of the battles on the track. Prost retired for a season in 1992 and came back in 1993 with Williams. That started another off-track feud that simmered for two years during 1992 and 1993 over a drive at the dominant Williams Renault team. Senna basically wished to be Prost's team-mate in 1993 in the best car. Prost would have none of it – it was reportedly written into his contract that Senna could not be his team-mate.

Gerhard Berger, Senna's team-mate at McLaren, has his own clear-cut ideas about why the Senna-Prost relationship was so full of conflict. "If you have someone like Ayrton or Schumacher as your team-mate then there are different ways you can handle it. At that time Ayrton was clearly the best and everyone knew that. Alain was in the same car and knew he didn't have a chance of beating Ayrton in speed terms, so he realised quite quickly that pace couldn't compensate. At that point he had the chance to say 'Okay, I'll find my own level and work at that, and get the team working with me as well'. But he refused to accept the situation so it all became political – he found fault with everything, and didn't hesitate to allocate blame. It caused a lot of aggravation and that was a problem for Ayrton, as he knew he was the best and that Alain was simply finding fault. It was clear there was going to be a big explosion."

Gerhard Berger, Senna's team-mate at McLaren, has his own clear-cut ideas about why the Senna-Prost relationship was so full of conflict. "If you have someone like Ayrton or Schumacher as your team-mate then there are different ways you can handle it. At that time Ayrton was clearly the best and everyone knew that. Alain was in the same car and knew he didn't have a chance of beating Ayrton in speed terms, so he realised quite quickly that pace couldn't compensate. At that point he had the chance to say 'Okay, I'll find my own level and work at that, and get the team working with me as well'. But he refused to accept the situation so it all became political – he found fault with everything, and didn't hesitate to allocate blame. It caused a lot of aggravation and that was a problem for Ayrton, as he knew he was the best and that Alain was simply finding fault. It was clear there was going to be a big explosion."

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 15

Special Issue

View from the Imola Paddock

The Feud with Prost

A Lesson in Safety

From Fangio to Schumacher

The Dark Side of the Man

Memories of May

Keith Sutton: The Senna Collection

Columns

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |