Atlas F1 Technical Writer

With few changes to Formula One's technical regulations, the season saw most of the teams introducing only evolutions of last year's cars. Nevertheless, there were still important innovations that proved development never stops in F1. Atlas F1's Craig Scarborough reviews the teams and the cars they raced in the 2003 season

The change to the sporting regulations forcing the teams to run race fuel and overnight 'parc ferme' procedures provided very little technical problems. However race strategy was affected, and the teams found their larger fuel tanks were unnecessary as none wished to incur the penalty of a heavy fuel load in final qualifying.

Overall the teams were split into the top four and the midfield, with Minardi and latterly Jordan falling into a third league, reflecting their lack of development resources.

Tyres

For the leading Michelin teams new tyres were provided early in the season which made use of a wider construction, with the aim of providing a larger contact patch for more grip. The teams had to compromise their aerodynamic efficiency in order to accommodate the wider tyre, now mounted nearer to the bodywork; this interrupted the flow and created more drag though having a larger frontal area.

Williams took up these tyres and soon found real gains; McLaren, not wishing to upset their more developed aero, preferred not to run the wider tyres at first. Michelin tyres were also believed to deform more in the corners under very heavy loads; this caused the tread to open out and present an even larger footprint to the track. The combination of both a wider tyre and the deformation caused Ferrari to examine the tyre widths after the races and lodged a protest just before Monza. The FIA upheld this protest and Michelin had to revert to the narrower construction for the balance of the season.

Flatter Front Wings

Since a rule change in 2001 raised the height of the front wing teams have striven to regain the lost downforce. There have been many variations of the so-called 'spoon' wing, with a curve to place the centre of the wing in closer proximity to the ground (as allowed in the rules). As teams developed better profiles for the wing they have recouped the lost downforce, and the pitch sensitivity of the 'spoon' wings has lead the teams to opt for flatter profiles.

Front wing endplate development has retained the banana shape philosophy where the endplates sweeps in between the front wheels, again keeping the trailing flow clear of the wheels. The shape of the lip running along the lower edge of the wheel has increasingly followed a Jaguar design pioneered by Ben Aganethalou where the lip forms a wavy profile. Renault, Ferrari and Toyota have also taken this route, some of them opting for a venturi shape over the constant wavy profile.

Complex Rear Wings

1. The outer sections run in clearer air, unobstructed by the airbox/rollover structure; this makes them more efficient.

2. The shorter outer chords produce smaller trailing vortices; these trails, often seen in damp weather, show where the flows form over and under the wing to the side of the endplate and meet, sending a spiral outwards, effectively making the wings frontal area larger; this produces drag.

3. The two contra rotating trailing vortices tend to pull the airflow behind the car upwards; this adversely affects the main flow through the wing and the wake from the underwing.

So although 3D wings may have had a deeper central section the more efficient design of outer section results in less drag, compensating for the draggier centre, that is the same downforce and drag from two very different wings. Many teams use these wings in some form; Ferrari have simply reshaped the wing profile just before it meets the endplate to reduce the vortices. Renault, BAR and McLaren have a seriously shaped version, as seen later in the season at Jaguar, Toyota and Sauber.

Team by Team

Ferrari F2003-GA

Starting the season with their previously all-conquering F2002 while the F2003GA completed its initial testing didn't do Ferrari any favours when we had three chaotic races through a mix of weather conditions and incidents. The old car was on the pace but never got to show its speed as luck turned away from the team. The F2002 was largely unchanged from its late 2002 spec, the team instead deciding to focus its development on the new car.

Brake ducts now wore a donut shaped outer ring to create an obvious path for the air from the brake to exit through the wheel in both a faster and less turbulent manner. Elsewhere the Ferrari initially wore familiar shapes; a spoon shaped front wing hung from a drooped nose leading to a deep single keel, while a smaller engine cover led to a conventional rear wing. Sidepods used variations on the single flip up and winglet, with chimneys wrapped around the exhaust to vent the sidepods.

But it was the layout that most affected the new car. Moving the front and rear axles forward pushed the weight distribution rearward as well as lengthening the wheelbase by 5cm. These changes were created by a shorter gear casing that now needed the upper rear wishbone re-packaged to mount to the rear of the engine. The longer nose allowed the distinctive scalloped sidepods to channel the air flowing over the front splitter more efficiently.

These changes were to exploit the amount of ballast Ferrari planned to shift between qualifying and the race to suit the needs of the Bridgestones. The Heathrow agreement quashed this plan, leaving Ferrari with a car unsuited to the new regs. Bridgestone's strategy left Ferrari with a tyre that ran 20-30 degrees hotter than Michelin, creating two problems; the lack of weight on the front left the tyres below temperature, inducing understeer, while the hot summer across Europe overheated the already marginal rubber.

Moving weight forward was already part of the F2003GAs intrinsic design; the front splitter looked like a Trivial Pursuit counter full of tungsten wedges but this was soon maxed out with ballast, leaving a little available to tune the car. However the resulting car understeered, reacted slowly to set up changes and abused its tyres.

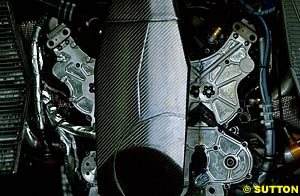

On the plus side the car displayed some fantastic traits, such as huge straight-line speed even when loaded with downforce as a result of the efficient long wheelbase shape and powerful engine. The engine was faultless all year with few reliability issues, as was the revised titanium gearbox, now using unique radial dampers from Sachs that were rotated by the pushrod rather than operated telescopically as with those of the other teams. These dampers do not suffer the nose pressure that most dampers suffer as they do not compress the oil into a chamber; instead the valves rotate through a reservoir of fluid. Rubens Barrichello suffered a suspension failure in Hungary, but this was attributed to a moment over the kerbs chasing Mark Webber rather than a genuine reliability issue.

Development throughout the year was muted; the rear wing soon had the outer edged knocked back in an attempt to reduce drag by minimising vortices shed from the endplate. Bargeboards were revised most, with the main boards seeing a variety of smaller secondary boards, some reaching deep under the nose. Silverstone saw a major revision with Renault-like wavy lip front wing endplates and slotted vents in the sidepod shoulders to vent the heat.

Williams FW25

With the loss of Geoff Willis as head of aerodynamics towards the end of 2002 Williams were expected to make a big jump, losing some of their conservatism for the new car. The car was launched quite late in February in Spain and was ready to run, as Williams wanted to start the season with the new car. On first glance the car didn't look too far removed from its predecessor, but details around the car hinted new approaches were in place. The front of the chassis and nose were raised and slimmed, while the cockpit surrounds and engine cover were also trimmed. One major concept change was the placement of mid placed bargeboards rather than the forward mounted set up favoured previously. The flip up treatment used extremely angled flaps with a slotted end to minimise separation, while the exhausts were flush to the bodywork with panels to install cooling chimneys.

From its first tests the car did not perform well; it lacked speed and stability and old parts for the FW24 were soon pressed into service on the new car, such as the bargeboard layout and wings. A crisis was developing and a major redesign was scheduled for the second and third rounds.

Generally the car lacked downforce, initially at the rear despite a modest front wing profile, the complex W front wing needed a lot of extra aero work at the rear to balance the car. As development progressed the rear end treatments grew simpler and tipped the car into more neutral handling.

The car soon had a new floor, wings and bargeboards, with the flip ups and winglets revised to create more downforce, both seeing a secondary aerofoil section added. This process continued, latterly under the tutelage of Frank Dernie, an ex-Williams aerodynamicist from the days before Willis or Newey. As head of development Dernie also took the role of Race engineer to Juan Pablo Montoya, who was struggling to find a good set up for his car. Race by race the car evolved heavily, seeing Ferrari style chimneys added to shroud the exhausts and later Renault-esque winglet/chimney combinations.

Silverstone saw a major revision with the flip ups and winglets being downsized through the adoption of a new floor and engine cover. Williams led the trend for fins along the spine of the engine cover to counter yaw at high speed. Closing the season Williams adopted the Ferrari donut outer brake duct and once more tested their BMW engine for next season, long before the end of the year.

The turnaround of the cars dynamics during the year was astounding; on top of the new parts on the cars the team rapidly understood the new qualifying rules, race engineers and Michelin tyres.

McLaren MP4-17D

Almost no other team could have managed the sheer workload McLaren burdened itself with during 2003. Such was their disadvantage to Ferrari last year the initial design for the 2003 car scrapped and a complete redesign was penned by Adrian Newey. To fulfil the need for an interim car the outgoing MP4-17 was also redesigned, keeping only the external shape of the monocoque. An 'interim' interim car was run through the winter tests until the definitive 2003 MP4-17D arrived before Melbourne, featuring revised aerodynamics around the bargeboards and front wing profile, plus an all-new rear end comprising the engine, gearbox and suspension.

The rear end now sported a lower and tidier gearbox and rear suspension, placing the dampers deeper inside the alloy casing. Among the other changes to the gearbox were the control systems; they did away with the clutch paddle on the steering wheel with the clutch automated during pit stops and spins.

Part of the effect of the rear-end redesign was revised weight distribution, moved forwards to better suit the Michelins tyres; last year's car lacked the scope of adjustment to accommodate the tyres. Unusually for McLaren they flew in winter testing rather than their usual understated testing times, which suggested that McLaren would blitz the opposition in the early part of the season before the new car took over form that position of dominance. Certainly the new car was on pace and had good reliability as the opening races fell to McLaren, who adapted to the changes to the race weekend and the weather conditions at each of the races.

However reliability did suffer, with Coulthard suffering the worst of the problems. While the opening of the season was playing out the new car failed to turn up to tests, and no launch date was scheduled. Rumours circulated wildly before the car finally broke cover, yet even this was interim car, lacking its definitive Carbon fibre cased gearbox. By the time the MP4-18 was running the team realised the MP4-17D had to continue to be developed to cover the new cars late debut.

Detail development continued almost invisibly, with only the new complex rear wing being noticed. It was not until the realisation that the world championship was slipping away that several developments from the MP4-18 were pressed on the MP4-17D. These included new front uprights with re-sited brake callipers and Ferrari-style barrel brake ducts, making McLaren the last team in F1 to adopt them. Aerodynamics were further bolstered with revised slim line sidepods and engine cover from the MP4-18, a simple hot air outlet, Ferrari-style exhaust chimneys and a single flip up along the flanks.

Renault R3

Confusingly Renault launched a dummy car to the media, comprising various elements of the old and new cars. What was clear was the similarity in the main external shapes, such as the high nose and rounded sidepods. Technical innovation was the gearbox made from carbon fibre bell housing and titanium gear case, topped by revised rear suspension.

Once testing was underway the new car adopted its definitive bodywork; prominent on the sidepods was the placement of the chimneys ahead of the winglets, opposing standard practice. Renault had found the flow from the chimney could be picked up by the strong vortex trailing from the outer edge of the winglet, improving its ability to pull hot air from the sidepods.

Renault's own wind tunnel and investment in rapid prototyping tools allowed it to bring aerodynamic revisions to almost every race, including some outlandish rear wings designed to cut drag by preventing the flow at the edges of the endplate forming drag-inducing vortices. This effective aerodynamic package was well matched to a supple suspension bringing the R23 chassis a lot of praise during the year.

Only at circuits where chassis and aerodynamic efficiency won over power outputs could Renault prove their pace. Monaco was a low point considering it was their best opportunity in the early part of the season; it was left until the Hungaroring's similar demands rewarded the car with a win. The car was always considered a threat at the start of a race; Renault's low line mechanical package and well-honed launch/traction control using the clutch as part of the system to reduce wheel spin.

BAR 005

As the first full car developed by ex-Williams aerodynamicist Geoff Willis many were unsure of the cars credentials; at its launch it was clear the car had been carefully thought out and a vision for its development was in place. Honda had developed a new lighter engine, no longer compromised by also having to fit into the Jordan chassis. Honda's involvement extended to the gearbox and control systems plus some limited involvement with the chassis. The car was visibly an extension of the BAR004 Willis had reworked during the 2002 season, retaining the aero treatments and chassis shape, but adopting newer thinking around the sidepods and in the car's construction.

Early races proved the car was not in fact heading the midfield pace, quite often with the team not getting the best out of the car as set up time was restricted due to reliability issues. Visual development soon started, with revised cooling outlets and winglets on the sidepods. BAR were amongst the first to adopt the complex rear wing design; clearly Willis' aero background was directing development.

As with many teams Silverstone saw a major upgrade, with new sidepods featuring a slimmer rear end and a pronounced bow in the winglets to direct the flow either side of the rear wing to improve its efficiency. Later in the season BAR found added input from Bridgestone in to its tyre development program, allowing BAR to get closer to their Michelin shod rivals.

Sauber C22

After a strong 2002 Sauber kept the key designs of the C21, such as the twin keel front end and familiar aero treatments, focusing instead their limited resources to package the Petronas-badged Ferrari engine to a revised gearbox. A lot of effort was put into lowering and slimming the car, but the launch version's square edged appearance gave away the fact the aero was developed in a commercial tunnel rather than their own. By designer Willi Rampf's own admission the relatively wide gearbox and bulky damper installation was a result of a lack of resources to reengineer the 2002 layout.

In early tests the car proved nimble and reliable, but soon appeared to lack pace in comparison to its rivals. Early season analysis by head of aerodynamics Seamus Mullarkey showed the issue to be aerodynamics, a result of inconsistencies between the wind tunnel results and track testing.

Visual development was not apparent until Silverstone, when the team started to run pastiches of the leading teams designs; a Renault rear wing shape, A Williams engine cover fin and Ferrari sidepods. More individual development was noticed in bargeboard design, where their aerodynamicists found solutions to create more downforce away from the wings or diffuser.

The complex board shape pulled flow from under the nose, creating lower pressure and hence downforce. Towards the last races of the year Sauber's pace improved dramatically from its better aero efficiency. With their own wind tunnel still not ready for commissioning until during the 2004 season, their potential for development remains limited.

Jaguar R4

Perhaps the surprise technically of 2003, Jaguar had spent 2002 trying to understand the recalcitrant R3, which suffered from just about every malady ever to be designed into a car. The results of this analysis were possibly compromised by a major re-shuffle of team personnel and drivers. The brief for the R4 was to create a simple conventional design, trying not to repeat the R3's errors.

The car was immediately on the pace, threatening the top four in qualifying and heading most of the midfield in the races. Yet as the opening races wore on into the European season Jaguar stayed at the head of the midfield pack; their simpler car and effective Michelins allowed the team to quickly extract the potential from the car. Reliability was an issue in the races, often robbing the better-positioned car of Mark Webber from points finishes and even more frequently retiring the second car of Antonio Pizzonia.

Development clearly centred on reliability and not pace, as the car altered very little during the season; indeed it was the only car not to have a major Silverstone redesign. This was a strategy of the Jaguar management to reap the rewards of a basically sound car while they invest more resources into the 2004 R5. This policy worked even up until the end of the year when Webber was able to lead Renaults and even Ferraris on days when the Michelins were the tyre to have. Their final seventh placing in the Constructor's Championship seemed a little harsh given the consistency of their pace all year, even if only for one car.

Toyota TF103

After a testing first year with a car that lacked downforce and grip Toyota had reason to worry about going into their second season, which traditionally is harder for new teams than their first. Added to this they were still using a commercial wind tunnel and not their own, which would not be fully commissioned until mid season.

Still, prior to the start of the season Toyota was feared by the midfield and even the top four raised concerns over their potential in 2003. As the first part of the season progressed the pace was not delivered, missing out on points in the opening rounds with disappointing pace and reliability. Lacking grip and aerodynamic efficiency, the failings of the TF102 were carried over in this car; the rear suspension seemed unable to cope with bumps or kerbs.

The poor chassis was matched to an engine that was on equal terms with the top three; straight-line speed is never a true judge of engine power as the inefficient chassis could not cope with lots of downforce, but this low downforce set up brought higher straight-line speeds.

Towards the mid season things were looking bleak for the TF103, which still lacked any aero development, but at Silverstone the fruits of the new wind tunnel were unveiled with revised bodywork through the car. Slimmer sidepods eschewed the older bulky outlet/flip ups, instead sporting a unique multiple winglet arrangement and slotted cooling outlets. Bargeboards were revised with Willis style forward placed barge boards matched to a fin across the front of the sidepod. Wings were revised with a complex rear wing mated to a W format front wing. Chassis development finally eased the rear suspension issues, freeing Toyota to challenge in the final races of the year.

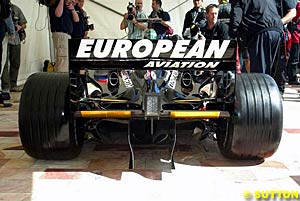

Jordan EJ13

As was the story for a lot of the midfield Jordan lacked the resources to design the unluckily numbered EJ13 for the 2003 season. After a lacklustre season in 2002 the team had regrouped to add Gary Anderson into a direction role between the racetrack and design office. Henri Durand remained head of design but with the emphasis on the aero work.

Aerodynamically the car was neater with sleeker lower lines but still wore the EJ12's sidepod winglets. A lower engine/airbox cover was allowed by the extremely low Jordan designed airbox that initially wore a hump shaped auxiliary oil tank until mid season to ensure reliability.

Early season reliability was also threatened by stress fractures on the alloy gearbox casing. The team bonded a carbon fibre skin to the affected area as a short term cure, subsequently finding that this also increased the stiffness of the casing to the point handling was improved. By Silverstone the whole casing was clad in a carbon skin.

Development on the car was limited during the season; small gurneys were added to the front wing struts, and a small vortex generator was added to the floor ahead of the sidepods.

Minardi PS03

Minardi, the last to unveil their new car; a progression from the PS02, the new car took the basic monocoque and gearbox from its predecessor and grafted on the Ford Cosworth customer engine.

The aerodynamics were conceived by Loic Bigois without much reference to a wind tunnel; only a few weeks of tunnel time we allowed in the budget, so they used their own model makers and occasionally the Fondmetal tunnel more frequently occupied by Renault's development team. Mechanically the car took its suspension layout from the older car and ran steel wishbones clad with carbon fibre.

Unsurprisingly the car lacked pace and reliability throughout the season; only a new front wing taking a curved appearance over the older stepped version marked early season development. By Monza a new sidepods treatment followed standard practice with the older triple flip up set up being discarded for a single large flip up and winglet.

After the third successive year with consistent technical regulations the cars have followed ever more convergent paths, with design elements being adopted by several teams. By the seasons end almost every team had adopted generic designs for front and rear wings, sidepod treatment and even bargeboard philosophies.

The battle was truly on this year; whereas in recent seasons Michelin needed specific conditions to operate at their best, this year they were on a par with Bridgestone at all types of circuit. Bridgestone had a single issue with their tyres all year; running over temperature. The hotter running of the tyres caused accelerated wear and degradation; this penalised the teams in the races as the tyres went off too quickly. Although Ferrari suffered they were able to remain competitive most of the time; the Bridgestone customer teams suffered much more, and the tyre rules allowing dedicated tyres for each team did not seem to bring the benefits for which they hoped. Across the season as a whole the Bridgestone customer tyres were not up the same pace as the Michelin customer tyres.

The battle was truly on this year; whereas in recent seasons Michelin needed specific conditions to operate at their best, this year they were on a par with Bridgestone at all types of circuit. Bridgestone had a single issue with their tyres all year; running over temperature. The hotter running of the tyres caused accelerated wear and degradation; this penalised the teams in the races as the tyres went off too quickly. Although Ferrari suffered they were able to remain competitive most of the time; the Bridgestone customer teams suffered much more, and the tyre rules allowing dedicated tyres for each team did not seem to bring the benefits for which they hoped. Across the season as a whole the Bridgestone customer tyres were not up the same pace as the Michelin customer tyres.

Williams and McLaren have taken this a stage further and developed wings with a W-shaped front profile; lifting and flattening the central section improves flow under the car, subsequently improving the efficiency of the rear diffuser. Their wing solutions also lifted the very outer most portion of the wing closest to the endplate, and as a result the W wing creates the majority of its downforce in the middle of the outer sections. This keeps the turbulent wake well clear of the wheels and bodywork, allowing for better brake cooling, smaller bargeboards and improving the quality of the general aerodynamic flow around the car.

Williams and McLaren have taken this a stage further and developed wings with a W-shaped front profile; lifting and flattening the central section improves flow under the car, subsequently improving the efficiency of the rear diffuser. Their wing solutions also lifted the very outer most portion of the wing closest to the endplate, and as a result the W wing creates the majority of its downforce in the middle of the outer sections. This keeps the turbulent wake well clear of the wheels and bodywork, allowing for better brake cooling, smaller bargeboards and improving the quality of the general aerodynamic flow around the car.

Rear wing development has also followed a Renault practice where the outer sections of the wing take a very different profile to that in the centre. Dubbed 3D wings as their profile alters in three dimensions, they run less drag for the same downforce as a 2D wing. The complex 3D shaped wings work on three basic factors.

Rear wing development has also followed a Renault practice where the outer sections of the wing take a very different profile to that in the centre. Dubbed 3D wings as their profile alters in three dimensions, they run less drag for the same downforce as a 2D wing. The complex 3D shaped wings work on three basic factors.

The new car sported some detail aerodynamic revisions in the sidepod shape, gearbox fairing and brake ducts. Ferrari altered their compound radiator layout to package the coolers closer to the car, allowing the sidepods to wrap tightly around the coolers and side-impact structures, forming a streamline shape. Flow over the rear of the car extended to a fairing wrapped around the gearbox to further smooth the flow.

The new car sported some detail aerodynamic revisions in the sidepod shape, gearbox fairing and brake ducts. Ferrari altered their compound radiator layout to package the coolers closer to the car, allowing the sidepods to wrap tightly around the coolers and side-impact structures, forming a streamline shape. Flow over the rear of the car extended to a fairing wrapped around the gearbox to further smooth the flow.

What was clear was the car had been substantially shortened from both of its predecessors; this was accomplished with a shortened gearbox. The P83 engine from BMW was running before the end of the previous season and its weight and installation were improved, although it does run a huge airbox. This combination of the airbox size and short gearbox gave a strange drop away shape to the rear of the engine cover. Over the first few races the large blister over the gearbox gave lie to the fact Williams were still running coil-over spring and dampers, a somewhat old technology in Formula One. In the team's efforts to deliver the FW25 to Australia the new rear suspension was held back, replaced by an interim version using old parts on the new gearbox.

What was clear was the car had been substantially shortened from both of its predecessors; this was accomplished with a shortened gearbox. The P83 engine from BMW was running before the end of the previous season and its weight and installation were improved, although it does run a huge airbox. This combination of the airbox size and short gearbox gave a strange drop away shape to the rear of the engine cover. Over the first few races the large blister over the gearbox gave lie to the fact Williams were still running coil-over spring and dampers, a somewhat old technology in Formula One. In the team's efforts to deliver the FW25 to Australia the new rear suspension was held back, replaced by an interim version using old parts on the new gearbox.

The detail of the front bargeboards was simplified from the enormously complex 2002 design, with the keel sporting a small low trailing board with smallish main board either side of the driver. McLaren were the first to adopt the W format front wing with the wing no longer dips under the nose but instead the centre section was flatter and the outer edges even higher. This left the majority of the downforce created by two small depressions on either of the mounting struts. While these do not create as much downforce they do allow a cleaner flow under the nose, improving the low pressure area created by the bargeboards under the nose and improving the flow to the diffuser at the rear of the car.

The detail of the front bargeboards was simplified from the enormously complex 2002 design, with the keel sporting a small low trailing board with smallish main board either side of the driver. McLaren were the first to adopt the W format front wing with the wing no longer dips under the nose but instead the centre section was flatter and the outer edges even higher. This left the majority of the downforce created by two small depressions on either of the mounting struts. While these do not create as much downforce they do allow a cleaner flow under the nose, improving the low pressure area created by the bargeboards under the nose and improving the flow to the diffuser at the rear of the car.

The engine was also deeply revised over the winter; an all new unit was created with balancers to counteract the vibrations in the wide angle engine. The engine installation was also improved, retaining struts across the top of the engine for stiffness and as yet unseen bottom mounts. The engine was much improved on power and reliability from 2002, but it was still some way short of the engines of their rivals.

The engine was also deeply revised over the winter; an all new unit was created with balancers to counteract the vibrations in the wide angle engine. The engine installation was also improved, retaining struts across the top of the engine for stiffness and as yet unseen bottom mounts. The engine was much improved on power and reliability from 2002, but it was still some way short of the engines of their rivals.

Initially the car looked very promising, with many teams regarding BAR as one of two teams to lead the midfield in 2003. As with most previous BARs the car soon displayed poor reliability, particularly with the hydraulic and gearbox systems. While the Honda engine held together more than in 2002, it was not a model of reliability.

Initially the car looked very promising, with many teams regarding BAR as one of two teams to lead the midfield in 2003. As with most previous BARs the car soon displayed poor reliability, particularly with the hydraulic and gearbox systems. While the Honda engine held together more than in 2002, it was not a model of reliability.

Sauber were often misunderstood to have run the whole Ferrari F2002 rear end on the car, but this is totally inaccurate; Sauber ran a Ferrari engine to which they added Marelli electronics plus their own design exhaust, airbox and gearbox. These additions were in line with Ferrari's recommendations and data, but in no way copied the F2002 layout.

Sauber were often misunderstood to have run the whole Ferrari F2002 rear end on the car, but this is totally inaccurate; Sauber ran a Ferrari engine to which they added Marelli electronics plus their own design exhaust, airbox and gearbox. These additions were in line with Ferrari's recommendations and data, but in no way copied the F2002 layout.

When the resulting R4 was wheeled in at a low budget internet-only launch things did not look promising, as the car borrowed heavily from its predecessor in concept and detail. Ford had commissioned an all-new 90-degree engine from Cosworth (badged as a Jaguar); the new even lighter and lower engine suffered reliability issues in early testing, although they were soon worked out. Otherwise the chassis used a triple (tricycle) keel layout with conventionally placed radiators, coil spring rear suspension and a bulky sidepod treatment.

When the resulting R4 was wheeled in at a low budget internet-only launch things did not look promising, as the car borrowed heavily from its predecessor in concept and detail. Ford had commissioned an all-new 90-degree engine from Cosworth (badged as a Jaguar); the new even lighter and lower engine suffered reliability issues in early testing, although they were soon worked out. Otherwise the chassis used a triple (tricycle) keel layout with conventionally placed radiators, coil spring rear suspension and a bulky sidepod treatment.

As a result the TF103 followed a logical progression from the 2002 TF102, keeping its general lines and instead focussing on the structure and systems not visible externally. Criticism was raised at Toyota for copying Ferrari's F2002, but more rational examination showed the adoption of exhaust fairings and small sidepod winglets was the design of choice across the field by the end of the season. Toyota still retained the bulky sidepod treatment, which was at odds with the complex radiator layout and protruding exhaust system.

As a result the TF103 followed a logical progression from the 2002 TF102, keeping its general lines and instead focussing on the structure and systems not visible externally. Criticism was raised at Toyota for copying Ferrari's F2002, but more rational examination showed the adoption of exhaust fairings and small sidepod winglets was the design of choice across the field by the end of the season. Toyota still retained the bulky sidepod treatment, which was at odds with the complex radiator layout and protruding exhaust system.

Initial work on the design of the new car centred around addressing the performance and complexity of all areas of the EJ12. This process focussed the design team to reduce production costs on all areas of the car, which was eased by the lighter, slimmer Ford Cosworth engine. Victims of this cost based reworking were the front torsion bar/damper layout and engine mounting spars. Improvements to the structures allowed the twin keel arrangement to be neater and without the horizontal strut to reinforce the keels.

Initial work on the design of the new car centred around addressing the performance and complexity of all areas of the EJ12. This process focussed the design team to reduce production costs on all areas of the car, which was eased by the lighter, slimmer Ford Cosworth engine. Victims of this cost based reworking were the front torsion bar/damper layout and engine mounting spars. Improvements to the structures allowed the twin keel arrangement to be neater and without the horizontal strut to reinforce the keels.

The new engine was a similar architecture to the Asiatech unit but had revised cooling, exhaust and induction requirements. Minardi were able to install a low line engine cover with exhausts protruding through the sidepods, while the radiators were installed vertically over the horizontal versions on the PS02.

The new engine was a similar architecture to the Asiatech unit but had revised cooling, exhaust and induction requirements. Minardi were able to install a low line engine cover with exhausts protruding through the sidepods, while the radiators were installed vertically over the horizontal versions on the PS02.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 43

2003 Season Review

2003 Race-by-Race Review

2003 Drivers Review

2003 Teams Review

2003 Technical Review

The Atlas F1 Top Ten

Atlas F1 Exclusive

Giancarlo Fisichella: Through the Visor

Columns

2003 Qualifying Differentials

2003 Trivia Quiz

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |