Atlas F1 Senior Writer

It has been a year now since Renault officially returned to Formula One, and it's time to take a closer look at how the French automaker goes about its business, beyond the glitz and frenzy of the launches of the R23. During the Christmas holiday hiatus, Renault Sport allowed Atlas F1's Thomas O'Keefe to access Renault Sport's factory at Viry-Chatillon, a suburb south of Paris, where the competition engines - that have made Renault world famous in motorsports - are born. He comes back with a newfound admiration for the national French effort, and looks back at where it went wrong the first time they tried. Exclusive for Atlas F1

Renault also built a tank called the FT-17 and it was so good that then-Captain George S. Patton, Jr. used the Renault tank to train what became his US Tank Corps. Louis Renault was given a medal after the war for Renault's contribution to ending World War I.

And in a real sense, Renault, as an industrial giant of international standing, continues to defend French honor, project French values and promote French technology to the rest of the world. Indeed, along with Renault's French tire supplier, Michelin, and French fuel supplier conglomerate Total/Elf/Fina, Renault F1 has come to embody French aspirations in motorsports.

But successful as Renault has been in war and in peace, to date a Formula One Championship has eluded the Regie's grasp, though it is certainly not for want of trying.

The Regie in Formula One, 1977-1985: Turbo Time

In 1977 and 1978, turbo teething problems plagued the car that Ken Tyrrell mockingly-christened as 'The Yellow Teapot' for its frequent turbo fires, although the cars were gradually becoming more competitive as the Renault engineers taught themselves turbo technology. In 1978, Renault finished 12th in the Formula One Constructors' Championship, nearly dead last, but could take some comfort from the victory in June 1978 at Le Mans of the spectacular-looking, long-tail Renault Alpine A442B turbo.

By 1979, Jabouille had shown early promise by taking pole at Kyalami in March 1979, but it took until July that year for Renault's big day to arrive, appropriately, at the French Grand Prix at Dijon-Prenois, where both turbos held together and Jabouille finished first and Arnoux third. This was truly an all-French d'affaires, which featured as its climax a spirited and legendary battle between the yellow Renault and French-Canadian Gilles Villeneuve in his red, non-turbo, flat 12- cylinder Ferrari, who managed to eke out second place after going wheel-to-wheel with Arnoux's Renault in the closing laps. Jabouille and Arnoux had also qualified 1-2 for the French Grand Prix, so after two and a half years of suffering and frustration, it appeared that Renault's engineering gamble on the turbo was beginning to give them the edge. Although there would be no more wins in 1979, Arnoux finished in the points sufficiently to boost Renault to sixth place amongst the Constructors.

After Renault's 1979 victory at the French Grand Prix, there was much more for Boisnard to film, as Renault steadily improved its reliability to the point where they won three races in both 1980 and 1981 and then four races in both the 1982 and 1983 seasons. By 1981, it was Alain Prost in Jabouille's seat (the great Renault pioneer driver who had been with the turbo project from the outset had his legs seriously injured in a crash in Canada) and, like Jabouille before him, Prost won the French Grand Prix at Dijon-Prenois in 1981, which was for Prost his first win. After that victory and two more in 1981 by Prost at Zandvoort and Monza, the English teams were no longer laughing at the Yellow Teapot, as envy was beginning to replace ridicule along the pitlane. And Ferrari was flattering Renault too, at least by imitation, having become in 1981 the second major constructor to use a turbo.

So turbos, skirts, hydraulically-actuated lowered sidepods, a "twin-chassis" from Lotus, carbon-fibre from McLaren, a drivers' strike, a rival series and money matters were all in the mix during the 1981/1982 seasons. But at the center was the gathering storm of the Renault and Ferrari turbos, which threatened to swallow up the assemblatore teams based in the UK - Brabham, Williams, Lotus, Tyrrell and McLaren.

Although the Concorde Agreement was in place by 1981, settling the business/sporting issues, back on the racetrack the technology wars continued, with the ultimate manifestation being the 1982 San Marino Grand Prix at Imola, which turned into a demonstration run for the Renault and Ferrari in the absence of most of the non-turbo British teams which boycotted the race. Both Prost and Arnoux won races in 1982 and took a stunning 10 pole positions between them, and Renault finished third in the Constructors' Championship, behind Ferrari and McLaren, for the second year in a row.

As the 1983 season unfolded, Renault was clearly in a position to capitalize on the steep learning curve both its engineers and drivers had climbed since 1977. By now, Renault had won the battle to establish turbo supremacy and even most of the British teams had turbos; Honda and Porsche had also gotten into the game, following the example of fellow manufacturer BMW, which had developed a 4-cylinder turbo for Bernie Ecclestone's Brabham - BMW BT52.

Renault, in addition to running its own team in 1983, made its turbo available to Lotus, supported by Mecachrome, the company to whom Renault subcontracted engine assembly. Prost was still team leader but American Eddie Cheever replaced Rene Arnoux, who had fallen from grace at Renault but landed a drive at Ferrari.

But although Prost would win at Spa (with Cheever again in third place) and also at Osterreichring and at Silverstone, by the summer of 1983, the other teams had markedly reduced Renault's technological advantage and no less than six constructors won at least one race during the 1983 season. The race for the World Drivers' and Constructors' Championship turned into a seesaw shootout among Piquet, Prost and Arnoux, for Brabham, Renault and Ferrari, respectively.

As the season came to a close at Kyalami for the South African Grand Prix, Arnoux had been all but mathematically eliminated and the World Drivers' Championship was going to be won by either Piquet or Prost. Earlier in the season at Zandvoort, Prost, having just won in Austria, tangled with Piquet at Tarzan corner, with Prost nudging Piquet off-course while Piquet was in the lead in an accident that put both cars out. Unfortunately, no such wheel-to-wheel drama accompanied the race at Kyalami, which Prost finished up on lap 35 of the 77 lap race when, you guessed it, his turbo failed, thus ending Renault's last, best effort to become a World Champion in its own right.

With his principal adversary out, Piquet cruised home in third place, which allowed him to win the 1983 Drivers' Championship by just two points over Alain Prost, who must have wondered then about that incident at Tarzan corner back in Holland in late August. Renault finished second in the Constructors' Championship, which remains as high as the Regie has ever ranked as a constructor.

Renault would continue in Formula One until the 1985 season but not with the same verve that accompanied the 1982 and 1983 seasons. Prost would go on to better things at McLaren in 1984 and thereafter, but for Renault, at least for the turbo era, the challenge was over as it withdrew from Formula One after nine seasons, with 15 wins to its credit. The unkindest cut of all was perhaps that the honor of the first turbo to win a World Championship would go to BMW and not to Renault which had started it all.

Not one to languish or cry over spilt milk, Renault did keep its hand in Formula One and go on to become a fabulously successful engine supplier to Lotus, Ligier, Williams and Benetton, adding drivers like Michael Schumacher, Nigel Mansell, Damon Hill and Jacques Villeneuve to Prost as drivers who became Champions in large part because their cars were powered by Renault.

The Regie Returns: Christmas Eve at Viry

Since Christian Contzen has worked for Renault his entire adult life, no one was happier when Patrick Faure, then-President of Renault Sport and himself a veteran of the Renault turbo era, convinced Renault's Board of Directors that it was time. Typically, when I visited Renault Sport at Viry-Chatillon during the Christmas holidays, Contzen was there at his desk, behind his computer, revelling that the return to Grand Prix racing he had been plotting for years was finally underway in earnest.

But if I was visiting Renault, what was I doing in an industrial suburb of Paris? Didn't we think Renault F1 operated out of Benetton's old factory in Oxfordshire, England, where most Formula One teams are located?

But Flavio also in a sense works at Viry and he and staff members from both sites fly back and forth regularly for meetings with the staff at Viry, which operates under the direct supervision of Frenchman Jean-Jacques His, who heads up Renault F1 in France, the group that develops those world-beating Renault engines.

It should be understood that Viry is not just a French address for Renault's public relations purposes but a very special place. Indeed, it is not going too far to say that Viry is an historic place that has served as the incubator of French engine technology for decades. How far back does Viry go? Viry was formerly the site of another motorsports effort that covered French racing blue in glory - the popular Gordini team (formerly the Simca-Gordini team), a perpetually underfunded sports car and Formula One team that attracted all the great French drivers of the era at one time or another - Wimille, Sommer, Trintignant and Behra - and enjoyed limited success in Formula One but had a loyal following until it raced its last Grand Prix at Monza in 1956.

It was also at Viry that the early Renault Grand Prix cars were assembled, both chassis and engine. Indeed, during my tour of Viry I saw at least two Yellow Teapots still on display in the building, one in a reception area and another one high up in the rafters overlooking the machine shop where prototype parts are machined on a spot, quick-turnaround basis for the race and test teams. Also on view to inspire those hard-working machinists, engine assemblers and exhaust system specialists are Schumacher's Benetton-Renault B195 that brought Flavio Briatore his one and only Renault-related World Championship, in 1995, and the blue and white Rothmans-sponsored Williams-Renault FW18 in which Jacques Villeneuve won the 1997 World Championship.

Indeed, it is obvious from being there that history and tradition play an important role at Renault F1, especially at Viry, beginning with the top man, Jean-Jacques His, who began his career as an engine designer at Viry, working on the V6 Turbo, only leaving Renault and Viry for Ferrari in 1986 (where he was head of Ferrari's Competition Engine and Gearbox Department) when Renault's works race team closed up shop. Today, he is back at the company that employed him right out of school, one of several living and breathing links with Renault F1 the first time around, able to have something few people ever get in life: a second chance to so something important, and this time to get it right.

His and the 260 people he supervises at Viry present an all-business, purposeful look. But interestingly - and contrary to what I had been led to believe - there was no sense of paranoia or secretiveness or excessive concerns about security as I was escorted around the factory by Serena Santolamazza, Communications Manager for Renault F1. The man working on a wiring loom had time to show us his collection built up over the years of ever-tinier and lighter alternators, and the exhaust system specialist displayed a working knowledge of the titanium exhaust pipes of Dan Gurney's Eagle as he showed us the prototype pipes being developed for the R23. I am sure no State Secrets were disgorged in what I was shown but the whole approach of Renault was more open than I had experienced on other factory tours.

The drivers themselves visit the troops at Viry several times a year and, of course, the test team that operates out of Viry sees them all the time. On race Sundays, a group of Renault employees, often including Jean-Jacques His himself, actually gathers at Viry to watch the races on Renault Sport's satellite link, only this group of fans has raw telemetry coming back to Viry from the racetrack to enliven the coverage they receive.

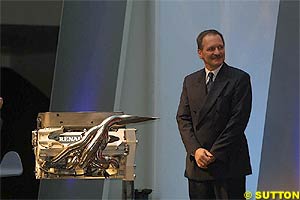

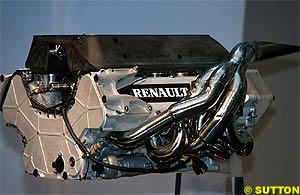

As you enter the factory, the reminders are everywhere that this is a building that designs engines. In one fabulous piece of square footage, all the Renault engines that have been designed at Viry are on display, from the Elf-Renault-Gordini turbo V6 to the V10 Renault/Supertec/Mecachrome iterations of the late 1990s , to a 3.5 litre V12 that was a beautiful brute I had never heard of, to the compact, 3.0 litre wide v-angle V10 that sits low in the rear of the current F1 cars.

Mecachrome, a precision engineering company based at Augigny-sur-Nere, near Bourges and not far from Magny-Cours, continues its longstanding relationship with Renault in assembling the racing engines that are designed and prototyped at Viry. The specs and parts for the engine are designed, produced and developed at Viry, the teardowns of the race and test engines and analysis of what is right and wrong are done at Viry, but Mecachrome actually assists Renault in the manufacture of the engines as a subcontractor to Renault Sport.

Nearby the Drivers' Gallery are two, one-third scale wind tunnel models of some of the more famous Renault collaborations: a Mansell-era yellow and blue Canon Williams-Renault FW14B from 1992 and a Hill/Villeneuve Rothmans Williams FW18 from 1996. Out front a full scale 2002 Renault Formula One car shares the lobby with one of the Yellow Teapots, so all bases are covered. To round out the picture, trophies won are enclosed in a glass case across from the drivers who won them.

Another thing about Renault is that nothing goes to waste at Viry. Cylinder heads and beautifully engineered pistons that have served out their useful life processing Elf's fuel are used to decorate the walls of one of the conference rooms and waiting areas, that Flavio Briatore and Jean-Jacques His use for their strategy sessions and monthly Steering Committee Meetings, creating the kind of sculptured artwork that would be worthy of a Museum of Modern Art.

Speaking of those engine parts, my tour includes a visit upstairs to the design area, which has the expected array of Computer Aided Design equipment, with people at their computer terminals designing parts or conferring with one another as they look at their monitors. I am told Adrian Newey at McLaren still works with pencils and a drafting board but I saw no pencils and paper in Renault Sport's design area. But Christian Contzen could be found working out amongst the younger CAD types on the design floor instead of being hidden away in some executive suite.

On the same floor with the computer/CAD people - but in their own designated area - the engineers who actually go to the racetrack are located, presumably promoting easy interchange of information between those who design and those who use what has been designed. Strategically placed conference rooms on this floor are plainly the way business gets done, even in an engine factory. Sprinkled throughout the partitions where people work is more evidence of Renault's success in racing, featuring plaques presented to the company to memorialize this or that victory or commendation, constant reminders to those privileged enough to work at Viry that they stand on the shoulders of those talented engine designers like His himself who came before them.

There seem to be at least three or four of what they call "test benches," but the rooms are not old-fashioned test benches but have the look of a NASA control room. I was allowed in to see the newest of the test facilities which was not then in use but passed by other test benches that were actually in operation, even during the Christmas season. The only time in my tour that furtive looks were exchanged was when I inadvertently (honest!) looked in on a group of mechanics strapping a new V10 into one of the test benches. No, I wasn't able to judge the v-angle but the engine looks remarkably wide, low and tiny for something that produces 800 plus horsepower.

Back in the state-of-the-art control room for the newest test bench, I was shown all the monitors, buttons, dials and controls and was told that Renault believes that this particular test bench is the most advanced one in operation and rivals anything in Formula One anywhere, including Maranello.

Once the engine is in the bay of the test bench - which reminded me a bit of a large intensive care facility, but for an engine instead of a person - it takes the Renault mechanics about four hours to "install" the engine to be tested and hook it up to all the exhaust systems and computerized sensors. Once the mechanics have the engine bolted down and connected to its various tubes, pipes and sensors, the engine room is cleared and the engineers in the control room take over, six or seven of them sitting behind computer screens and consoles running the tests and simulations. (I noticed they were Hewlett-Packard computers, by the way, principal sponsors of BMW-Williams!)

In the old days, the engineers would actually "drive" the engine being tested using a shifter as they brought the revs up and put the engine through its paces, which actually looked like a lot of fun. Today, the engineers feed in the data for a particular track and run the engine for two hours or more in a simulated Grand Prix. Conditions inside the test bench room can be environmentally controlled, to better simulate track conditions. Until recently, Hockenheim - with its long straights through the forest that tended to stress the engine most - was considered the Gold Standard used in test simulations. But since Herman Tilke's re-design of Hockenheim last year, Monza has become the new standard to simulate the highest levels of engine stress. It is from control rooms like this that the engine mapping is developed that will find its way into the electronics of the engine on race day.

How many of these engines that Renault Sport produces go to a race? As of the 2002 season, 12 engines were taken to each race, with all new internal parts. Once used at a race, the engine is torn down and inspected and the ever-thrifty Renault engineers will re-use parts if possible in the test engines - not all parts (pistons for example are not salvaged except to decorate the walls) but some like the camshafts are re-usable. As to the value of each engine, as open as Renault Sport was, they were not about to break down the cost accounting for me. Looking at it another way, Renault did say that each engine is insured for 1 million French francs (about $150,000 USD), so that as the transporters roll out for a Grand Prix, some insurance company has 12 million French francs of valuables being insured in the form of the engines taken to every race.

Continuing the tour, we came to what was my favorite part of the Viry factory - the machine shop, which is located on the same floor as the test benches. This is where you can see, feel and touch the parts that those CAD machines have designed and those test bench computer consoles have run through the wringer. Even more importantly when it comes to Formula One - where new bits are everything - the men and women who work in the machine shop are proud of their capacity to produce new parts for the engines or exhaust systems in as little as two hours from the time their clients - the CAD people, the test team or the race team - bring them specs. It is here amongst the drills and lathes that we see engines being built by hand as they have been from time immemorial and the Yellow Teapot, Benetton-Renault and Williams-Renault which grace the machine shop area and are hoisted on high for all to see, supply the tangible proof that what these machinists do every day can produce a champion Formula One car.

* * *

Delage, Delahaye, Talbot, Ligier, Bugatti and Gordini are all French companies that once proudly waved the tricolor and wore French racing blue in Grand Prix racing, all gone now from the scene. Prost is gone and the turbo era is too, but France and the Regie live on in the form of Renault, and you sense in meeting them that the passion to win beats in the breast of all of those boffins and techies at Viry and Chipping Norton as it once did in the hearts of Ettore Bugatti, Amadeo Gordini, and, of course Marcel and Louis Renault.

Renault has not chosen a particularly propitious time to re-enter Formula One, given the smothering dominance of Ferrari and a piranha tank that is even more crowded now with major league manufacturers like Ford, Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Honda and Toyota than it was when Renault made its first grasp at the ring. To be sure, at one time or other, Renault has beaten most of these manufacturers with the engines that were designed and prototyped at Viry and that must inspire the men and women of Renault to keep at it, knowing they have the support of one of the world's top car makers behind them.

Everyone knows that a Renault AK 90V riding on Michelin tires won what is generally regarded as the first Grand Prix, the 1906 Automobile Club de France Grand Prix, held on the Circuit de la Sarthe near Le Mans. But did you also know that Renault fought with distinction in World War I when, out of desperation, on September 6th 1914, the Military Governor of Paris commandeered 600 Renault Taxicabs to rush troops to the front, which was then northeast of Paris, in the Battle of the Marne?

By packing five infantrymen into each Renault Taxi, 4,000 soldiers were ferried to the Marne and it turned out that those troops supplied the decisive element of reinforcement needed to successfully repel the attempted invasion of Paris by the Germans. The legend of the Marne Taxi's is a treasured chapter in French military history and one of the remaining Renault "Marne Taxis" has an honored place in France's Musee de l'Armee, which is a part of the Invalides complex in Paris, where Napoleon's tomb is also located.

By packing five infantrymen into each Renault Taxi, 4,000 soldiers were ferried to the Marne and it turned out that those troops supplied the decisive element of reinforcement needed to successfully repel the attempted invasion of Paris by the Germans. The legend of the Marne Taxi's is a treasured chapter in French military history and one of the remaining Renault "Marne Taxis" has an honored place in France's Musee de l'Armee, which is a part of the Invalides complex in Paris, where Napoleon's tomb is also located.

In late 1976, Renault commenced its first assault on Formula One with an all-French initiative: traditional partner Elf provided the financial backing to develop a 1.5 litre version of the Renault-Gordini V6 turbo already successfully being used in sports car racing, in an era when most Grand Prix engines were conventional 3.0 litre Cosworth DFV's. Michelin supplied the sticky radial slicks and the initial Renault drivers were Jean-Pierre Jabouille and Rene Arnoux, followed in time by Alain Prost.

In late 1976, Renault commenced its first assault on Formula One with an all-French initiative: traditional partner Elf provided the financial backing to develop a 1.5 litre version of the Renault-Gordini V6 turbo already successfully being used in sports car racing, in an era when most Grand Prix engines were conventional 3.0 litre Cosworth DFV's. Michelin supplied the sticky radial slicks and the initial Renault drivers were Jean-Pierre Jabouille and Rene Arnoux, followed in time by Alain Prost.

By this time, the brightly painted yellow, black and white livery of the Renault turbos were already destined to become famous because, notwithstanding their less than stellar performance on the racetrack, the Renault turbos were turning in fabulous performances as movie stars. Why? Because Elf, for promotional purposes, had retained French film maker Alain Boisnard, to produce films about the Renault/Elf turbo project and in the process Boisnard developed novel camera positions and angles from which to film various parts of Grand Prix weekends. As a result of his efforts, a considerable amount of archival footage of the turbo era has come down to us, not only of the yellow Renaults and other Elf-sponsored cars but also of long lost Formula One tracks such as Kyalami, the Osterreichring, Anderstorp, Zandvoort, Jarama, Watkins Glen and Long Beach, where the Renaults ran.

By this time, the brightly painted yellow, black and white livery of the Renault turbos were already destined to become famous because, notwithstanding their less than stellar performance on the racetrack, the Renault turbos were turning in fabulous performances as movie stars. Why? Because Elf, for promotional purposes, had retained French film maker Alain Boisnard, to produce films about the Renault/Elf turbo project and in the process Boisnard developed novel camera positions and angles from which to film various parts of Grand Prix weekends. As a result of his efforts, a considerable amount of archival footage of the turbo era has come down to us, not only of the yellow Renaults and other Elf-sponsored cars but also of long lost Formula One tracks such as Kyalami, the Osterreichring, Anderstorp, Zandvoort, Jarama, Watkins Glen and Long Beach, where the Renaults ran.

In retrospect, and in light of the current turmoil in the sport we are experiencing, 1981 was also a time of foment and excitement in Formula One at all levels - business, sporting regulations and technology - and much of the fuss was the result of the by then obvious success of turbo technology introduced by Renault. While Ferrari was content to copy the V6 turbo concept and simply hoped to beat Renault at its own game, the English teams resisted the costs of revamping to adapt to the turbos and were simultaneously in battles with the governing body over control of the business aspects of the sport - the so-called FOCA/FISA wars - as well as regulations over "skirts" that were then being used to increase downforce.

In retrospect, and in light of the current turmoil in the sport we are experiencing, 1981 was also a time of foment and excitement in Formula One at all levels - business, sporting regulations and technology - and much of the fuss was the result of the by then obvious success of turbo technology introduced by Renault. While Ferrari was content to copy the V6 turbo concept and simply hoped to beat Renault at its own game, the English teams resisted the costs of revamping to adapt to the turbos and were simultaneously in battles with the governing body over control of the business aspects of the sport - the so-called FOCA/FISA wars - as well as regulations over "skirts" that were then being used to increase downforce.

But in looking back on the 1982 season, it must be said that with 10 poles in a 16 race calendar, it was clearly a missed opportunity for Renault, as the cars ran up front all year long at a variety of tracks - a pole and win at Kyalami and Brazil, both Prost and Arnoux on the front row at Spa, Arnoux on pole at Monaco - both drivers contributing, but costly spins and accidents putting the cars out more than engine reliability for a change. Worse still, Rene Arnoux, who had won pole at Paul Ricard for the French Grand Prix and was leading the race, found himself in a position similar to that of Rubens Barrichello in Austria 2001 and 2002, but unlike Barrichello, Arnoux refused to follow team orders and let second-placed Prost by for the win at a time when Prost was better positioned to win the Drivers' Championship. Needless to say, Arnoux's self-centered behavior did not endear him to his superiors at Renault.

But in looking back on the 1982 season, it must be said that with 10 poles in a 16 race calendar, it was clearly a missed opportunity for Renault, as the cars ran up front all year long at a variety of tracks - a pole and win at Kyalami and Brazil, both Prost and Arnoux on the front row at Spa, Arnoux on pole at Monaco - both drivers contributing, but costly spins and accidents putting the cars out more than engine reliability for a change. Worse still, Rene Arnoux, who had won pole at Paul Ricard for the French Grand Prix and was leading the race, found himself in a position similar to that of Rubens Barrichello in Austria 2001 and 2002, but unlike Barrichello, Arnoux refused to follow team orders and let second-placed Prost by for the win at a time when Prost was better positioned to win the Drivers' Championship. Needless to say, Arnoux's self-centered behavior did not endear him to his superiors at Renault.

In the first race of the season in Brazil, at Rio de Janeiro, the blue and white Gordon Murray-designed "Parmalat" Brabham-BMW BT 52 turbo, driven by Brazilian Nelson Piquet, showed its muscle by winning the race over 1982 World Champion Keke Rosberg's Williams-Ford. Renault got off to a slow start but the third race of the season in 1983 happened to be the French Grand Prix at Paul Ricard, a circuit the Renault team knew well. So Prost was on pole next to Cheever, and Prost won the race ahead of Piquet, which foreshadowed the struggle all year long between Renault and Brabham-BMW. Meanwhile, Cheever joined Prost on the podium in third place for the kind of successful home race that injected new life into Renault's season.

In the first race of the season in Brazil, at Rio de Janeiro, the blue and white Gordon Murray-designed "Parmalat" Brabham-BMW BT 52 turbo, driven by Brazilian Nelson Piquet, showed its muscle by winning the race over 1982 World Champion Keke Rosberg's Williams-Ford. Renault got off to a slow start but the third race of the season in 1983 happened to be the French Grand Prix at Paul Ricard, a circuit the Renault team knew well. So Prost was on pole next to Cheever, and Prost won the race ahead of Piquet, which foreshadowed the struggle all year long between Renault and Brabham-BMW. Meanwhile, Cheever joined Prost on the podium in third place for the kind of successful home race that injected new life into Renault's season.

For a firm as proud as Renault, it must have been gnawing at them institutionally to have tried so hard at Formula One in the 1970s and 1980s, only to come up short. But although Renault disappeared from the grid as a constructor, Renault Sport's Managing Director, Christian Contzen, persuaded his superiors to establish a technical surveillance team to keep abreast of what was happening in Formula One, to keep a foot in the door so to speak - just in case there was a change of heart at the top and the orders came down to gear up for a return to Formula One.

For a firm as proud as Renault, it must have been gnawing at them institutionally to have tried so hard at Formula One in the 1970s and 1980s, only to come up short. But although Renault disappeared from the grid as a constructor, Renault Sport's Managing Director, Christian Contzen, persuaded his superiors to establish a technical surveillance team to keep abreast of what was happening in Formula One, to keep a foot in the door so to speak - just in case there was a change of heart at the top and the orders came down to gear up for a return to Formula One.

Yes and No. Never one to do things in the easy way, Renault F1 operates out of two separate facilities in two different countries separated by the English Channel: in Viry, Renault works on the now-famous wide-angle V10 engine, its exhaust system and its electronics; in Oxfordshire, England (Enstone, Chipping Norton to be exact), the chassis and suspension bits are fabricated in what was formerly Benetton's home base, which also has its own state-of-the-art wind tunnel and some 350 people operating under Technical Director Mike Gascoyne, a Briton formerly with Jordan. Renault F1 UK Managing Director Flavio Briatore goes to work at Chipping Norton everyday, as he did when he ran the Benetton team when it won its two World Championships in 1994-95.

Yes and No. Never one to do things in the easy way, Renault F1 operates out of two separate facilities in two different countries separated by the English Channel: in Viry, Renault works on the now-famous wide-angle V10 engine, its exhaust system and its electronics; in Oxfordshire, England (Enstone, Chipping Norton to be exact), the chassis and suspension bits are fabricated in what was formerly Benetton's home base, which also has its own state-of-the-art wind tunnel and some 350 people operating under Technical Director Mike Gascoyne, a Briton formerly with Jordan. Renault F1 UK Managing Director Flavio Briatore goes to work at Chipping Norton everyday, as he did when he ran the Benetton team when it won its two World Championships in 1994-95.

When Gordini merged into Renault in the late 1960s, the ex-Gordini works at Viry became the headquarters for Renault Sport and continues as such even today. It was at Viry that Renault Sports's General Manager, an ex-Gordini man, Francois Castaing, and his young engineers Bernard Dudot and Pierre Boudy developed the Renault turbo, wrestling with turbo lag, intercooling and the thermal problems created by the massive temperatures affecting the internal parts of the engines.

When Gordini merged into Renault in the late 1960s, the ex-Gordini works at Viry became the headquarters for Renault Sport and continues as such even today. It was at Viry that Renault Sports's General Manager, an ex-Gordini man, Francois Castaing, and his young engineers Bernard Dudot and Pierre Boudy developed the Renault turbo, wrestling with turbo lag, intercooling and the thermal problems created by the massive temperatures affecting the internal parts of the engines.

And Viry does very much feel like a factory, although an elegant, clean, modernistic one. Unlike the ex-Benetton factory in Enstone that Renault acquired from Benetton in 2002, Viry is not spread out amongst acres of greenery of the English countryside but is instead located in an industrial park in one large building, where space is at a premium. The Viry building is much longer than it is wide, almost as if it was originally built as an assembly line, and it is squeezed in amongst other manufacturing facilities that have nothing to do with Renault Sport. After you get through the courteous security people and the parking lot, you pass by the Renault F1 transporters, just back from testing in Spain, parked right next to the building, their precious cargo being unloaded.

And Viry does very much feel like a factory, although an elegant, clean, modernistic one. Unlike the ex-Benetton factory in Enstone that Renault acquired from Benetton in 2002, Viry is not spread out amongst acres of greenery of the English countryside but is instead located in an industrial park in one large building, where space is at a premium. The Viry building is much longer than it is wide, almost as if it was originally built as an assembly line, and it is squeezed in amongst other manufacturing facilities that have nothing to do with Renault Sport. After you get through the courteous security people and the parking lot, you pass by the Renault F1 transporters, just back from testing in Spain, parked right next to the building, their precious cargo being unloaded.

Just past the alcove where the engines are on display is Renault Sport's Drivers' Gallery, which collects in one place pictures of the 36 or so drivers Renault claims as its own, from Jabouille who was there at the beginning, to Fernando Alonso, the 21 year-old Spaniard upon whom much depends if Renault is ever to achieve its goal of a World Championship. Included among the glossy photos of the fresh-faced drivers are pictures of all the drivers who drove for Renault directly or who drove for other constructors who used Renault engines, thus the 36 drivers in the Gallery. Fair enough for Renault to take credit for all of them, which is why Renault F1's public relations material states that Renault's record in Formula One includes 135 pole positions, 94 Grand Prix wins and 11 World Championships, albeit all without actually winning The Big One!

Just past the alcove where the engines are on display is Renault Sport's Drivers' Gallery, which collects in one place pictures of the 36 or so drivers Renault claims as its own, from Jabouille who was there at the beginning, to Fernando Alonso, the 21 year-old Spaniard upon whom much depends if Renault is ever to achieve its goal of a World Championship. Included among the glossy photos of the fresh-faced drivers are pictures of all the drivers who drove for Renault directly or who drove for other constructors who used Renault engines, thus the 36 drivers in the Gallery. Fair enough for Renault to take credit for all of them, which is why Renault F1's public relations material states that Renault's record in Formula One includes 135 pole positions, 94 Grand Prix wins and 11 World Championships, albeit all without actually winning The Big One!

Having left the hush of the carpeted design area upstairs, I was surprised and thrilled to be taken downstairs to the belly of the beast, where the tool and machine shop is, where the wiring and electronics people work and, most importantly, where Renault Sport's engine testing facilities are located.

Having left the hush of the carpeted design area upstairs, I was surprised and thrilled to be taken downstairs to the belly of the beast, where the tool and machine shop is, where the wiring and electronics people work and, most importantly, where Renault Sport's engine testing facilities are located.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 4

Atlas F1 Special

Renault in Formula One: Take Two

Back to the Future: The FIASCO War

Articles

Battle at BAR

Columns

Bookworm Critique

Rear View Mirror

Elsewhere in Racing

The Grapevine

> Homepage |