Backward glances at racing history

Atlas F1 Columnist

A (Winston Smith) History Lesson

In 1922, the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnu (AIACR), which was renamed the Federation Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) in the wake of the Second World War (1946), created the Commission Sportive Internationale (CSI). It was not until May 1925 that the CSI managed to produce a draft of what would become the "International Sporting Code." Well, actually, the draft was offered for the consideration of the CSI by the Automobile Club de France (ACF). By October of 1925, discussions which had also included a set of counter-proposals by the Royal Automobile Club of Great Britain, had simmered down to a point where the CSI adopted the Code. The effective date for the new Code was 1 January 1926. Since that date there has been a never-ending series of changes to the Code.

The term "Grand Prix" is simply the French term for "Grand Prize." Many countries use the equivalent - "Grosser Preis" or "Gran Premio" for instance - for their major events, while the English-speaking countries seem to find, for some reason, a preference for the French term versus the use of "Grand Prize" when appropriate. In the United States, the "Grand Prize Race of the Automobile Club of America" was run from 1908 until 1916, later being teamed with the "William K. Vanderbilt Cup Race."

"Grande Epreuve" does not translate very well from the French into English, but means roughly "Grand Event" or perhaps "Great Trial." This grandiloquent term came into use by The Blazers at the CSI to designate certain events as being major or significant events on the sporting calendar. Naturally, by the mid-1930's this included the Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France and the International 500-Mile Sweepstakes, from prior to the Great War. Postwar events included the Gran Premio d'Italia, the Grand Prix de Belgique, the Grosser Preis von Deutschland, the Gran Premio de España, the Grand Prix de Monaco, the Royal Automobile Club British Grand Prix, and - curiously - the Grosser Preis der Schweiz. In addition, the Royal Automobile Club Tourist Trophy and Les Vingt Quatre Heures du Mans were listed as Grandes Epreuve.

Here is something from a statement concerning the achievements of Michael Schumacher: Michael Schumacher's 60th win in a Grande Epreuve (Grand Prix of a national state.)…. Reading this piqued my attention since I was unaware that his total number of victories in the events listed above came to the number quoted. Silly me, I was clueless that the definition of this term, Grande Epreuve, was changed to mean something different. More on this in a moment.

Here are is another statement that caught my eye: At 22 he (Bruce McLaren) was the youngest driver ever to win a Grande Epreuve. At the ripe old age of 22 years and 103 days, Bruce McLaren was finishing his first full season of Grand Prix racing when he won the II United States Grand Prix at Sebring, mounted aboard a Cooper Coventry Climax. However, first of all, the United States was not a Grande Epreuve, or least not at the time. Troy Ruttmann, on the other hand did win a Grande Epreuve - which was also a round in the CSI World Championship for Drivers, the 1952 International Sweepstakes, at the age of 22 years and 80 days.

Which allows the following statement to be introduced:

It is all in the name.

"The reality is that a Grand Prix is not what counts," says ITV commentator James Allen. "The thing that matters is whether or not the event was what is called a Grande Epreuve, an event which counts for the World Championship. The 11 Indianapolis 500s in the 1950s were not Grands Prix but they were World Championship events, even if the European teams and driver completely ignored them. So they do count in the overall count."

With this statement tossed in for good measure: Common acceptance is that F1 dates to 1950, as do its records. Oh, my...

Well, back to the term "Grand Prix." There is no lock on the use of the term "Grand Prix" in motor racing. The first running of the Canadian Grand Prix was not in 1967, when the race was run in the rain at Mosport, but in 1961 when American Peter Ryan won the race in a Lotus 19 powered by a Coventry Climax FPF. From 1961 until 1966, the Canadian Grand Prix was run using sports cars. It was still the Canadian Grand Prix and should not disappear from the record books simply because it was not run to the "International Formula One" as it is (was) formally named by the CSI.

The first true international racing "formula" was that laid down for the running of the Coupe Internationale, or as it is best known, the Gordon-Bennett Cup. It was run from 1900 until 1905. The essential elements of the "formula" were:

In 1906, the Automobile Club de France introduced the first "Grand Prix" formula for its race, the ACF boycotting the Gordon-Bennett series which subsequently folded after the 1905 Coupe Internationale. The sticking point was limiting each country to only three entries. At the time, France was the leading car-producing country and felt that the three-car limit was too restrictive. The Gordon-Bennett organizers were unmoved by this argument. So, the ACF organized its own race.

In 1907, the "formula" for the Grand Prix de l'ACF was an allocation of 30 litres of fuel per 100 kilometers. In 1908, what has become known as the "Ostend Formula" was introduced. It called for a minimum weight of 1,100 kilograms. Four cylinder engines to have a maximum bore of 155 millimeters and a maximum bore of 127 millimeters for six cylinder engines. The stroke was unrestricted. The weight did not include water, fuel, tools, protective parts, and spare tires.

The ACF did not hold events from 1909 through 1911. This was due in great part to a business recession which struck the automotive business very hard and the manufacturers decided the expense to field cars for The Grand Prix simply was not warranted. After being a serious contender in the early days of racing, Renault departed the sport not to return until the late-1970's. The action in the motor sports arena was largely in America at this time, the Grand Prize and Vanderbilt Cup events being the major events of the period. In 1911, the United States added a third event to its Grand Prize/Vanderbilt Cup duo, the International 500-Mile Sweepstakes run at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

In 1912, the Grand Prix de l'ACF returned. It was basically a free-for-all event, the ACF not making any stipulations as to a "formula" for the event. In 1913, there was the stipulation that the cars had to have a minimum weight of 800 kilograms and a maximum weight of 1,100 kilograms. The cars were restricted to 20 litres per 100 kilometers as well. In 1914, the "Grand Prix" formula was pretty straight forward: a minimum weight of 1,100 kilograms and a maximum engine capacity of 4,500 cubic inches.

In 1920, the International Sweepstakes was run to a formula with a maximum displacement of 3,000 cubic centimeters for the engines. In 1921, the ACF adopted the American formula, but added the requirement that the cars had to have a minimum weight of 800 kilograms.

In 1922, the maximum capacity was reduced to 2,000 cubic centimeters and minimum weight of 650 kilograms. The end of the car could not project beyond the center of the back axle by more than 150 centimeters. The car had to carry two passengers with a combined weight of at least 120 kilograms.

In 1925, just in time for the first World Championship that the CSI sponsored, the requirement for two passengers was eliminated, but the minimum cockpit opening was 80 centimeters and two seats were required to be fitted to the cars. The first World Championship event sanctioned by the CSI was the 1925 running of the International Sweepstakes and the inaugural winner was Duesenberg - the championship being for manufacturers rather than drivers. When the season was over, Alfa Romeo emerged as the first CSI World Champion. It is during this period that the term "Grande Epreuve" emerges. Apparently, the term was used to signify rounds in the new World Championship.

In 1926, the maximum displacement was dropped to 1,500 cubic centimeters and a minimum weight of 600 kilograms. There remained the minimum of 80 centimeters for the cockpit opening and that two seats had to be fitted. Bugatti was the World Champion for this season. In 1927, the only change was an increase to 700 kilograms for the minimum weight. Delage emerged as the World Champion for this season.

In 1928, the formula was changed to a minimum race distance of 600 kilometers with a minimum weight of 550 kilograms and a maximum weight of 750 kilograms. The CSI World Championship was cancelled for 1928. Although once again scheduled for the 1929 and 1930 seasons, it was never held again. In 1929, there was a minimum weight of 900 kilograms and an allocation of a maximum of 14 kilograms for fuel and oil per 100 kilometers of an event. In 1930, the minimum weight remained the same, but there was a minimum engine displacement of 1,100 cubic centimeters. There was an addition allowance of 30 percent for cars using "benzol" as fuel on top of the 14 kilograms.

Due to the poor economic climate, the Depression, from 1931 until 1933 the "international" races in Europe were essentially run for whatever showed up, the only "formula" being the race distance. In 1931, the minimum race duration was 10 hours, with a co-driver being allowed. There was also an European Championship introduced by the CSI, Ferdinando Minoia winning the title while driving an Alfa Romeo. He did it, incidentally, without winning a single event, barely squeaking by his teammate Giuseppe Campari.

In 1932, the minimum race duration was five hours and the maximum duration 10 hours. In what can scarcely be described with much clarity without going into no end of permutations, the CSI devised its European Champion as a contest between entries from the manufacturers and private entrants, the factory team competing against the owner-drivers. In the end, the 1932 European Champion was Alfa Romeo, with the second placed Tazio Nuvolari being the first owner-driver and generally recognized as the champion driver of the season, but not "the champion."

In 1933, an event had to be over a distance of at least 500 kilometers. That was it. There was no CSI European Championship in 1933. Nor was there one in 1934.

In late 1932, the CSI announced the formula - now generally referred to as the "International Formula" - for the 1934 through 1936 seasons. The formula called for a maximum weight of not more than 750 kilograms. Not counting towards the minimum weight stipulation were the fuel, oil, tools, and tires. The cars were theoretically "dry" when weighed. There was a minimum cockpit opening of 85 centimeters. There were no restrictions on the fuel used.

In 1935, the CSI revived its European Championship. All the champions were German drivers, naturally enough, particularly since the racing departments at Daimler-Benz and the newly formed Auto-Union managed to push the technical envelope and build machines with far more power at their disposal than The Blazers at the CSI ever anticipated. The 1935 European Champion was Rudolf Caracciola, driving a Mercedes-Benz. He was to repeat in 1937 and 1938. In 1936, the European Champion was Bernd Rosemeyer, driving for Auto-Union.

After seeing how they missed the boat on the 750 kilogram formula, the CSI finally devised a formula in late 1936 to see if there might be some hope for others to give the Germans a run for their money. Efforts to have a new formula in place for 1937 were foiled by fundamental disagreements as to what the formula "look" like. One of the problems with the German domination was that Grand Prix racing was waning away. In 1934, there had been a large number of event run using the International Formula: 37, of which seven were considered to be Grandes Epreuve. By the 1936 season, it had dropped to 25 - with only four being considered in the Grande Epreuve category.

In 1937, the numbers dropped slightly, to 23, but with an increase to five in the Grande Epreuve class. At first glance, it appeared that the new International Formula might be just the thing to bring the French and the Italians back into the game. One thing that was clear, however, was that the 1938 season saw only 11 events run to the new International Formula. Five of them were Grandes Epreuve, the International Sweepstakes having been run to the CSI formula for the first time since 1927.

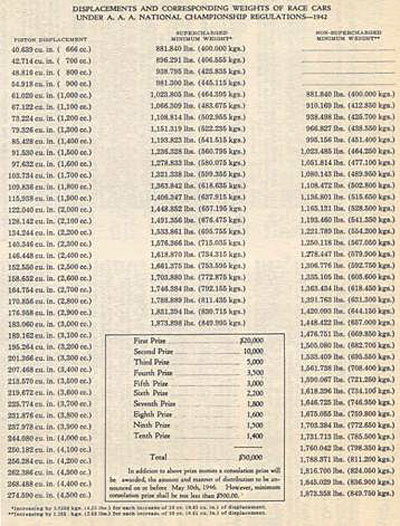

Here is a reproduction of the rather elusive sliding weight-displacement table that the CSI devised for the new International Formula:

It may be of some interest to realize that it was taken from the entry form for the 1946 International Sweepstakes, being placed on the entry forms for events comprising the American Automobile Association (AAA) Contest Board's National Championship Trail since 1938. For some reason, there seems to be a dearth of such tables in Europe.

An aside on the International Sweepstakes: the Speedway itself, in its programs and other publicity items, referred to the 500-mile races from 1938 until in the immediate post-Second World War years as the "Indianapolis Grand Prix." It was a Grande Epreuve in fact as well as using the term as an honorific.

Usually about all that is said is that the minimum displacement for a supercharged engine was 666 cubic centimeters with a maximum displacement of 3,000 cubic centimeters. For unsupercharged engines, the minimum displacement was 1,000 cubic centimeters and the maximum displacement was 4,500 cubic centimeters. The minimum weight for a machine was 400 kilograms at the lowest displacements and 800 kilograms at the upper end of the displacement table.

The formula was scheduled to run through the 1940 season. The policy of giving a year's notice prior to a change in the formula could have meant that there may have been a possibility of adopting the Voiturette formula into the International Formula in 1941. For 1931, the CSI introduced a new Voiturette formula, the engines having a maximum displacement of 1,500 cubic centimeter and with supercharging being permitted. As the German domination of Grand Prix racing reduced the opportunities for both marques and drivers to participate in the premiere series, the Voiturette formula went from strength to strength during the latter part of the 1930's.

With the Germans active in Grand Prix racing, in 1937 the Italians turned their attention more and more towards the Voiturette class. Maserati was one of the mainstays of the class. For 1938, Alfa Romeo built up a team of cars, the Tipo 158, for the class. The parts were made at the factory, but assembled in the shop of the former entrant for Alfa Romeo, Scuderia Ferrari. In addition to the Italians, the British were achieving a measure of success with the E.R.A. machines. When the Mercedes team showed up at the Gran Premio di Tripoli in May 1939 with a pair of Voiturette machines - the Italians had decided to run all their major events to the Voiturette formula for 1939 - there was much to be said for the next International Formula having a supercharged 1,500 cubic centimeter component.

However, the dogs of war were unleashed in early September of 1939 and the racing season came to a close. A scheduled meeting of the CSI in October never took place and any discussion of the future was deferred. Nor did the CSI officially announce who the European Champion was for 1939. Even to this day there is some confusion and many questions concerning this championship. Using the scoring system employed in the previous championships, the champion should have been H.P. Muller, a member of the Auto-Union team. However, in December 1939 Korpsfuhrer Adolf Huhnlein, the head of both the NSKK (the National Socialist Drivers Organization) and the ONS (Oberste Nationale Sportbehörde or roughly the National Sporting Authority) declared that Hermann Lang was the 1939 European Champion.

Other than the minor problem that Korpsführer Adolf Huhnlein had absolutely no authority from the CSI to make such a decision, much less an announcement to that effect, the problem is that it is Lang who has passed down through the years as the champion for that season. Complicating things even more, there are indications that the CSI was perhaps considering a change in the scoring system for 1939. Worse, there is some evidence that even as late as the Swiss Grand Prix in August that there was clearly some confusion over the scoring and the standings. To add insult to injury, when the CSI met after the Second World War, it did nothing to clarify this situation. That the decision concerned which of two German drivers would get the nod obviously played a significant part in this lack of urgency to resolve the issue.

After the Second World War finally ended, the AIACR met and formally changed its name to the current FIA in 1946. The CSI continued on under the FIA, but its president, the Belgian le Chevalier Rene de Knyff, who had led the CSI since its founding in 1922 stepped down and was replaced by the Frenchman Augustin Perouse. Little wonder the 1939 championship was not a priority.

The first order of business of the CSI was to pick up the pieces of international racing, particularly in Europe, and get things moving again. Sports involving resources such as fuel, lubricants, and scarce items made of high quality metals, were not a high priority in the immediate recovery efforts that were taking place. However, the urge to compete and the need for some diversions to steer the people away from despairing about their current lot in life extended to motor sports as well as that staple, football.

In the latter part of 1946, the CSI agreed to a new international formula. It was designed to take advantage of what was generally available. With the Germans now absent from the scene, plus the popularity of the Voiturette formula prior to the War - to say nothing of the fact that there were far more Voiturette cars available than those built for the former Grand Prix formula - the new "International Formula A" allowed supercharged engines with displacements of up to 1,500 cubic centimeters. In addition, with a knowing nod towards another supply of cars - French interestingly enough, the displacement for unsupercharged cars was set at 4,500 cubic centimeters. There were no minimum or maximum weight limits imposed. One of the more difficult problems in holding a race was cleverly addressed by the CSI - the organizers of an event had to provide the fuel for the cars.

The effective date of the new International Formula A was intended to be 1 January 1948 - as was the new International Formula B for cars with unsupercharged engines of up to 2,000 cubic centimeters or 500 cubic centimeters supercharged. Things being what they were, most of those organizing major events in Europe immediately adopted the new formula for their 1947 events. At the end of 1948, the stipulation that the organizers had to provide the fuel was dropped.

In the United States, in late 1946 the AAA Contest Board approved the new International Formula A as the basis for its events beginning in 1948. However, in 1947 there was a temporary extension of the use of cars using supercharged engines of up to 3,000 cubic centimeters until the smaller engines were available in greater numbers for use. So, although the "temporary" extension continued and was made permanent several years later, the United States had formally accepted the use of the International Formula A for its national series. That the vast majority of the engines used in the events on the National Championship Trail were unsupercharged Offenhauser engines - with the firm of Meyer-Drake now building and maintaining them - with a displacement of 4,500 cubic centimeters is significant. They were, in essence, "Grand Prix" cars. Perhaps not in the way most would think of using the term, but the notion was clearly there.

In 1949, after the first season of the newly organized World Championships sanctioned by the Federation Internationale Motocyliste, the CSI entertained a motion from the Italian representatives that a similar World Championship series be inaugurated for the following year, 1950, the Championnat du Monde des Conducteurs - the World Championship of Drivers. For 1950, the CSI approved the idea and put together a series of events for the championship, one of the rounds being the International Sweepstakes. This was not merely a sop to American interests - which it was, but recognition of the fact that the race was a genuine Grande Epreuve and had been included in the first CSI World Championship in 1925. The only change to the International Formula A/ I/ 1, was that the events should have a minimum distance of 300 kilometers and a minimum duration of three hours. This was clearly intended for the Grande Epreuve races, although many of the other races run to the International Formula One also met these criteria.

So, before 1950 there was "F1." By the 1950 season, "International Formula A" and "International Formula B" had become "Formula I" and "Formula II" - but usually now simply "Formula One" (F1) and "Formula Two" (F2). 1950 merely gets attention because of the CSI decision to launch a new World Championship that season. Formula One/F1 was already in existence and record books already written when the Royal Automobile Club British Grand Prix, which was also given the grandiose and basically meaningless title as the Grand Prix d'Europe.

In 1951, the CSI announced a new International Formula One to become effective on 1 January 1954. It reduced the maximum displacement of unsupercharged engines to 2,500 cubic centimeters and that of supercharged engines to 750 cubic centimeters. In March 1952, S.A. dei Prodotti Alfa Romeo announced that it would not be participating in the CSI World Championship - or similar events that season. The announcement was not unexpected. The problem for promoters was that it essentially left the grid open for Scuderia Ferrari. That is, unless the BRM team chose to contest at least the major (European) events - at least those being in the Grande Epreuve category - and provide competition to Ferrari. There were clear doubts as to whether BRM would make this commitment. The organizers of the various major racing events in Europe were nervous as they contemplated the thin grids and thinner crowds at their events. Not waiting to see how the wind would blow, the organizers of the Gran Premio di Siracusa changed their event from International Formula One to Formula Two. They were taking no chances and although it was still a small field, all Ferraris on the grid, they did give many others pause as they considered their situation.

At the Gran Premio del Valentino, held on the circuit snaking through the Parc Valentino in Torino, it was anticipated that the BRM team would make an appearance. For a number of reasons, which were many and varied in the contemporary accounts, BRM was a no-show and the stampede to Formula Two by the race organizers in Europe was on. One by one, the events counting for the CSI World Championship converted to International Formula Two. The CSI rolled with the punches and simply stated that it would recognize these events as championship events. The only Grande Epreuve run to the International Formula One in 1952 and 1953 was the International Sweepstakes.

The situation with the International Sweepstakes and the CSI and both its World Championship and International Formula One took several turns in the 1954 period. The AAA Contest Board had originally agreed to adopt the new CSI International Formula One, but after a lobbying effort among some of the members postponed the implementation for at least a season. And then it was postponed for another season. However, the CSI continued to count the International Sweepstakes as a round in its World Championship, largely based on the continuing efforts of the Contest Board to adopt the International Formula One for the National Championship Trail.

The latter postponement ended up being an indefinite one. After the death of Bill Vukovich at the 1955 International Sweepstakes - along with the deaths of several other drivers in events sanctioned by the Contest Board - and the disaster at Le Mans, in August 1955, the President of the AAA abruptly announced that its Contest Board would terminate its operations at the end of that year.

The new organization replacing the Contest Board in the operation of the National Championship Trail, the United States Auto Club (USAC), was much more focused in the smooth transition from one organization to another to be overly concerned about such items as the adoption of the International Formula One for its events. In 1956, the USAC reduced engine displacements for safety reasons and the 1957 season. However, the CSI continued to list the International Sweepstakes as a round in the World Championship.

In late - as in very late - 1957, the CSI dictated some changes to the International Formula One. After finding general satisfaction with the displacement limits, the minimum duration of an event counting towards the World Championship was reduced to two hours and fuel was now standardized as 100/130 octane aviation gasoline (AVGAS) simply because it was the only form of fuel readily available throughout the world which was the same regardless of location. This was done after the fuel companies lobbied for some commercial concessions as a result of their bearing much of the cost of premiere level racing. Or so it has been said.

In November 1958, the CSI announced a new International Formula One. In doing so, it sent a rocket into the heart of British motor racing. The new formula called for unsupercharged engines with displacements between 1,300 and 1,500 cubic centimeters. It also reintroduce the notion of a minimum weight, placing it initially at 500 kilograms, later being reduced to 450 kilograms. The formula was take effect on 1 January 1961.

At this point, the future of the International Sweepstakes on the World Championship calendar was clearly doomed. The USAC board was adamantly opposed to the formula. The directors of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway make it clear what they thought of the new formula by simply refusing to even consider it as a possible alternative to the current USAC formula. Therefore, there was little protest when the International Sweepstakes was dropped from the World Championship calendar - although still being listed as a Grande Epreuve - for 1961. There is great irony in this timing. Within just a few short years, the International Sweepstakes would be back on the center stage as a true Grande Epreuve with the best of both Europe and America battling it out at the Speedway.

After rambling about for a bit, let me wind up with the masterpiece of Winston Smith, something so slick that it went right by almost everyone not only at the time, but in the years since. In the early stages of the FIASCO Wars, the struggle between the FISA and the Formula One Constructors' Association - FOCA (a story mostly already told), the President of the Federation Internationale du Sport Automobile (FISA), Jean-Marie Balestre did a pre-emptive strike that whistled right by just about every one when it - he killed the Championnat du Monde des Conducteurs (the World Championship of Drivers) that the CSI had established in late 1949.

On 15 April 1980, Balestre proposed to the FIA Rio Congress that the current championship be terminated (the word used in the English translation is "suppressed"). Instead, Balestre proposed that as of 1 January 1981, there be the "FIA Formula One World Championship." Unlike the World Championship began by the CSI, this new - note the word - championship would be the property of the FIA and the FISA would act as its agent plenipotentiary. This was clearly meant to convey that the FIA and the FISA owned the championship, including all the commercial and financial aspects of the series. This also meant that the FIA/FISA owned the title, something that it didn't beforehand.

The old championship officially ceased to exist on 31 December 1980. Unlike the "new" championship, the "old" championship was not run exclusively to International Formula One. The International Sweepstakes events from 1954 to 1960, along with the events of 1952 and 1953 which were run to the International Formula Two (the International Sweepstakes being the exception), are proof of this.

In December 1969, during a period when some scarcely concealed ill will existed between the FOCA and the CSI and the organizers - it was to get worse by 1972, the CSI authorized race organizers to add F2 cars (properly ballasted to the F1 minimum weight, of course) to the grid of World Championship events if it were that there were insufficient entries. In 1972, the CSI threatened to support the organizers to throwing open the World Championship to not only F1 and F2 cars, but those complying to the F5000 and USAC formula as well. However, when it came to the crunch, the CSI backed down while the FOCA didn't even blink.

So, perhaps now it is common acceptance the FIA F1 World Championship and its records dates back to the 1981 season. One of the things that came about as a result of this "new" championship is that all - as in each and every one - rounds in the FIA F1 WDC are now considered to be a Grande Epreuve, whether the event dates back to 1906, 1911, or is new this year. So much for the answer that should have been given as to whether something is a Grand Prix or a Grande Epreuve...

So, Winston Smith just glides us through all that - and other issues - by ensuring that the history fits what is now the common acceptance of these things.

The Truth is Rarely Pure, and Never Simple - Oscar Wilde

There is controversy as to whether the (2003) Brazilian GP is really F1's 700th World Championship race. The race had been billed as the 700th event in the history of the Formula One World Championship - but there have been arguments that the landmark will not be reached until the Italian Grand Prix in September. The problem is whether the 11 Indianapolis 500s which were included in the championship between 1950 and 1960 were actual Grands Prix or not.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 49

Articles

In the Matter of da Matta

The French Revolution

Burning Rubber, Burning Oil

2004 Countdown: Facts & Stats

Columns

Rear View Mirror

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |