Atlas F1 Senior Writer

Atlas F1's Thomas O'Keefe visited the legendary Nurburgring circuit last month, for the 2003 European Grand Prix. He recalled how a rookie who never as much as seen a Formula One race before, let alone drive an F1 car, made history some 40 years ago, and he reviewed what veteran fans do at a place whose every mile holds the stuff of Grand Prix legends. If you're ever in the neighbourhood, these are the things you don't want to miss out on...

But this reasonably successful modern Formula One track, no matter how hard it tries to please, cannot help but suffer by comparison to the Nordschleife, the historic Nurburgring track that preceded it, the one that sits in the valley below a twelfth-century castle named Schloss Nurburg that gave the circuit its name, the one that Ronnie Bucknum drove on.

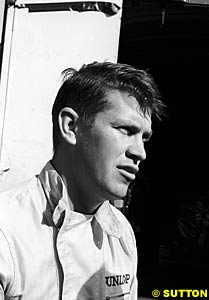

Who was Ronnie Bucknum? Born in 1936 and deceased in 1992, he was the American sports car driver chosen by Honda in 1964 to drive its Formula One car, the first time Honda entered the sport of Grand Prix racing, when the Power of Soichiro Honda's Dreams was just beginning to take hold and Honda was barely a car company much less a Grand Prix Constructor.

Far from the obvious choice, Bucknum was nevertheless from a good racing pedigree, having competed in the fast and furious California sports car circuit amongst the great American drivers who had already made their way to Grand Prix racing: Dan Gurney, Phil Hill and Richie Ginther. Later in life, Bucknum proved to be a quick study

in oval track racing, winning the fast and dangerous Michigan 500 in only his second time out in an Indycar.

Incredibly, three weeks later, on August 2nd 1964, he was no longer in the grandstands but on the same grid as Clark's green and yellow Lotus, with Bucknum in the cockpit of the off-white Honda RA271 with a red rising sun on its scuttle, at Nurburgring of all places - the Old Nurburgring, the real thing, flying platzs, bridges, hedge rows, two mile long straights, more than 173 turns and trees everywhere. A single lap of the Nurburgring at that time took eight and a half minutes since the circuit was 14.17 miles (23 km) long. Surely it is one of the most spectacular debut Grand Prix rides of all time that Ronnie Bucknum undertook that day in the Eifel Mountains.

How did Bucknum prepare for this baptism of fire? After seeing the race at Brands Hatch, he and his wife traveled to Germany, and Dan Gurney took the fellow Californian and Old Yeller driver (they had both driven Max Balchowsky's crowd-pleasing yellow Buick-powered special with whitewall tires at different times in their careers) for some laps around the Ring in a Mercedes sedan, Gurney having raced there the past two seasons himself, finishing third in 1962 in a flat-8 air-cooled Porsche 804 Grand Prix car. But Bucknum did not stop there. According to Tim Considine's book "American Grand Prix Racing", Bucknum then drafted his wife into the act and the two of them went round and round the Nordschleife in a rented Volkswagen, with his wife knitting and Bucknum memorizing. For the race organizers he had to do a minimum of 5 laps in the race car and he did that too and was placed last on the grid.

Tazio Nuvolari left the Luftwaffe above and the Nazi Generals below in the grandstands aghast when he won the 1935 German Grand Prix in the aging Alfa Romeo P3 over the much more powerful but tire-killing Mercedes-Benz W25 and Auto Union Type B.

In the 1957 German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring, Juan Manuel Fangio in his lightweight Maserati 250F performed an equally unlikely feat, defeating the more powerful Ferrari 801s of Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins by following a tactic still in vogue today - running on a light fuel load in the early stages of the races, then after topping up the fuel, reeling the two Ferraris in during the last lap on fresher tires.

In 1961, Stirling Moss in Rob Walker's Lotus 18 also won against the superior Sharknose Ferraris of von Trips and Hill in the kind of wet/dry changeable weather race so characteristic of the Eifel Mountain circuit, when Moss chose Dunlop wet tires at the outset of the race and the damp and later torrential conditions played into his hands, giving him his last Grand Prix win and another triumph for the underdog at the Ring.

One of the unique aspects of going to a race at the new Nurburgring that one cannot replicate anywhere else on the Grand Prix tour is that there are remnants here and there of the glorious past of the Nordschleife. One set of artifacts I found particularly surprising to discover is the old sunken garage area of the Nordschleife, the Historisches Fahrerlager, with a tunnel that leads up to the track that is still there, the same place where the Great Ones walked: Caracciola, Rosemeyer, Nuvolari, von Brauchitsch, von Trips, Stuck, Fangio, Moss, Surtees, Clark, Gurney, Stewart, Rindt and Andretti.

The smallish garages, of which there are about 50 still being used, provided a paddock area for the BMW open-wheel support series on the European Grand Prix weekend. One of the commentator booths from the 1930s has also been preserved just about the garage area. I wondered how many of the pimply-faced drivers and their girlfriends - Clearasil should be the series sponsor - knew where they were standing.

To the credit of the German people and track owner Nurburgring GmbH, no one has bulldozed the track and built time-share condominiums on it, and except for race weekends, you can actually venture out there in your road car and see what it was like for all these legends of the sport, being careful to avoid the fate of drivers like Peter Collins, Onofre Marimon and Carl Godin de Beaufort, who died at the Old Ring. To this day, people hurt themselves and others overdoing the privilege of being permitted to drive on hallowed ground.

Indeed, there is lots to do at the Nurburgring throughout the year, including a museum, kart track and a taxi service that will get you around the track in one piece. Call Alexandra van Otterdijk of Erlebniswelt, at 0 26 91/3 02 603, to plan your trip around a Grand Prix Legend.

All you do is walk five minutes from the main gate of the new track in the direction of the town of Nurburg and follow the signs to stand 13 (Tribune 13 as the Germans put it), and before you know it you are at the top of the serpentine Hatzenbach just before it descends, somewhat reminiscent of the corkscrew turn at Laguna Seca.

But you will not be alone as you make your way through the Hatzenbach esses. On a weekend like the European Grand Prix, the great old asphalt supports a tent city on either side of the road, all the way from the top of Hatzenbach down through the next turn, Hockeichen (2 kilometers out from Nurburg), and almost up to the Flugplatz (4 km), one of the famous flying places where photographers have captured airborne all the greats that have run here from the High Summer of the Silver Arrows to the rear-engined Brabhams, Coopers and Lotuses of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Hatzenbach Tent City has a population of at least 2,000 people. These people are the equivalent of season ticket holders at any sport anywhere, except that they bring their cars, caravans and tents of all sorts and come early in the week and stay past Sunday, making a vacation out of camping on a legend. Their ingenuity and camaraderie are a sight to behold, Hatzenbach being the kind of tent city that caters not only to the students and noisy, beer-swilling young men you might expect, but many families out for a holiday, their VW, BMW, Alfa Romeo or Land Rover towing a caravan of some kind.

Fires cook up bratwurst galore. No police as such patrol Hatzenbach Tent City but a car from the circuit manager's office circulates from time to time to lend some aura of authority. On one pass, some German campers dragging two medium size logs from the thick forest surrounding the area were gently chastised by the track management patrol car, presumably for deforestation but they were allowed to drag off what they had foraged to their campsite.

In addition to Udo's bus on the Hatzenbach Tent City run, a more sedate bus service runs on the Nordschleife in the other direction out of the town of Nurburg, this time for 17 km from Hohenrain to Pflanzgarten corner. There is also a mountain bike route around the Nordschleife for those not patient enough for Udo's bus. However you get around it, with the towering trees, the mists on the hillsides, the narrow track, the well worn red and white candy-striped kerbings, some of which look like they go back to the 1927 beginnings of the track, the dramatic changes in elevation and the sense of imminent danger that lurks around every corner, all of it is very much the world Ronnie Bucknum came to know in his first Grand Prix at the Nordschleife back in 1964, which would look very familiar to him if he could be transported back there today for one last run.

To be sure, Bucknum and Honda both did themselves proud in the course of their joint debut at the Nordschleife. There are pictures of the RA271 in that part of the Nurburgring garage area that is still preserved today which show the car at the earliest stages of the race weekend, no race numbers yet painted on, Bucknum in the cockpit of the car looking apprehensive as his Japanese mechanics hover nearly having just poured in a few churns of fuel.

The Honda looked a bit of an ugly duckling that day, with its copycat Lotus/Cooper-like front end and a slab-sided rear end behind the cockpit that accommodated the ear-splitting Honda V12. The engine was fitted transversely in the rear, carburetors and exhaust pipes sprouting everywhere, an innovative and powerful alchemy of Honda's motorcycle engineering tradition and conventional Formula One technology. Bucknum adapted well enough to have the new Honda running as high as 11th place before the mechanical gremlins struck and Bucknum spun out of the race with four laps left. The post-race forensic analysis of the Honda RA271 exculpated Bucknum, who was victimized by a broken steering which resulted from metal failure, not a driver error.

Honda's second and last Grand Prix victory was also achieved without Bucknum. At the end of the 1967 Italian Grand Prix, John Surtees brought an Anglo/American/Japanese special built around a Lola Indianapolis chassis and dubbed the "Hondola" in as the winner at Monza in a close finish with Jack Brabham that went down to the last turn at Parabolica and could easily have gone the other way. By the time Surtees scored his 1967 victory at Monza, both Bucknum and Ginther had been given their walking papers, with Honda focusing its efforts on one driver that the company felt comfortable with, ex-motorcycle champion and ex-Formula One champion John Surtees.

But none of this takes away from the tenacity and commitment Bucknum showed in August 1964, when he was thrown into the worst of possible circumstances - driving an untried, brand new Grand Prix car that was constructed by a company more used to creating motorcycles than open-wheel race cars on the most daunting racetrack in the world. While he may not have been a winner for the Honda Grand Prix team as was Ginther and Surtees, Bucknum was an integral link in the chain of events that led to Honda's eventual domination of Formula One by 1991 as an engine supplier to McLaren and Williams. For Honda and Bucknum, it all started at the Nurburgring, where so much Grand Prix history has been made.

It is doubtful that 80 years from now, when Grands Prix are being held in places like Shanghai, Moscow, Turkey, Bahrain, Dubai and India, that people will come and visit the new 2.8 mile Nurburgring racetrack, nice as it is, but there is no question that as long as cars have wheels and people have memories, the magnificent old Nordschleife racetrack laid out under the Schloss Nurburg castle will remain a treasured reminder of the men and machines that have made our sport. Take a lap next time you are there and think of Ronnie Bucknum.

I got to thinking about Ronnie Bucknum when I was at the Nurburgring for the 2003 European Grand Prix, as it dawned on me that on August 2nd 2003 it will be 39 years since Bucknum and Honda made history at the track they call the Ring.

Today, we have a 2.8 mile circuit with the evocative name "Nurburgring" that was built in 1984. It has the new, wide, Herman Tilke-designed Mercedes turn in the early part of the track that is supposed to engender passing, and the Veedol/NGK chicane on the back side of the course, which actually does promote passing. It has the fast and dramatic sweeping Coca Cola Kurve that passes by the trackside Dorint Hotel, where the rich and famous camp out for the weekend as the tracks winds its way by the Dorint and on to the start-finish line on the main straightaway.

Today, we have a 2.8 mile circuit with the evocative name "Nurburgring" that was built in 1984. It has the new, wide, Herman Tilke-designed Mercedes turn in the early part of the track that is supposed to engender passing, and the Veedol/NGK chicane on the back side of the course, which actually does promote passing. It has the fast and dramatic sweeping Coca Cola Kurve that passes by the trackside Dorint Hotel, where the rich and famous camp out for the weekend as the tracks winds its way by the Dorint and on to the start-finish line on the main straightaway.

But that was in 1968. When he got the call just around the time of the Sebring 12 hour endurance race in 1964 from Honda to be interviewed in Japan to become Honda's one and only Grand Prix driver for that season, Bucknum had never raced a single-seater. Indeed, Bucknum was so new to Formula One that he had never even been to a Grand Prix until July 11th 1964, when he and his wife and Yoshio Nakamura, the head of Honda's Formula One effort, took in the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch, the first time the race was held there, where they saw Jim Clark win in his Lotus 25.

But that was in 1968. When he got the call just around the time of the Sebring 12 hour endurance race in 1964 from Honda to be interviewed in Japan to become Honda's one and only Grand Prix driver for that season, Bucknum had never raced a single-seater. Indeed, Bucknum was so new to Formula One that he had never even been to a Grand Prix until July 11th 1964, when he and his wife and Yoshio Nakamura, the head of Honda's Formula One effort, took in the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch, the first time the race was held there, where they saw Jim Clark win in his Lotus 25.

Long before Bucknum had his hour on the stage at the Nurburgring, everyone who was anyone in Grand Prix racing had earned their spurs at this magnificent racetrack. Rudolf Caracciola (from Remagen on the Rhine river, not too far from Nurburg) raced there in the first real German Grand Prix in 1927 and won the 1928 race in his Mercedes SS as he began his transformation from car dealer to the most successful German driver before Michael Schumacher.

Long before Bucknum had his hour on the stage at the Nurburgring, everyone who was anyone in Grand Prix racing had earned their spurs at this magnificent racetrack. Rudolf Caracciola (from Remagen on the Rhine river, not too far from Nurburg) raced there in the first real German Grand Prix in 1927 and won the 1928 race in his Mercedes SS as he began his transformation from car dealer to the most successful German driver before Michael Schumacher.

And then there is poor Niki Lauda, whose fiery accident at Bergwerk in his Ferrari 312T2 in 1976 left him with horrible burns on his scalp and ears that mark him still and sounded the death knell for this fabulous racetrack which had now shown itself to be out of step with modern Formula One - too dangerous, too long and too antiquated to be saved.

And then there is poor Niki Lauda, whose fiery accident at Bergwerk in his Ferrari 312T2 in 1976 left him with horrible burns on his scalp and ears that mark him still and sounded the death knell for this fabulous racetrack which had now shown itself to be out of step with modern Formula One - too dangerous, too long and too antiquated to be saved.

On race weekend when most of us get to the track, you cannot drive around the Nordschliefe but you can catch glimpses of its majesty in a couple of ways. First, that part of the Nordschleife that comes tantalizing close to the new track is a series of downhill twisty bits called the Hatzenbach kurves. Even for the non-aerobic amongst us, this is an easy hike and an absolute must if you want to get a feel for what a real racetrack looks like.

On race weekend when most of us get to the track, you cannot drive around the Nordschliefe but you can catch glimpses of its majesty in a couple of ways. First, that part of the Nordschleife that comes tantalizing close to the new track is a series of downhill twisty bits called the Hatzenbach kurves. Even for the non-aerobic amongst us, this is an easy hike and an absolute must if you want to get a feel for what a real racetrack looks like.

And the best part of Hatzenbach Tent City for you the visitor is that, incredibly, they even have their own Hatzenbach Kurve Bus service, a shuttle that runs for roughly the full 4 km from the town of Nurburg down the racetrack and back again, from 6 A.M. to 7 P.M. My bus driver, Udo Zanzen of nearby Bodenbach, was so popular with the instant community that developed on the Nordschleife that as he made his occasional stops (no formal bus stops mind you, just pickup points wherever two or more banded together and hailed the bus down), it was common for the campers to come up not for a ride but to offer Udo food and drink from the grilles and coolers that dotted the landscape.

And the best part of Hatzenbach Tent City for you the visitor is that, incredibly, they even have their own Hatzenbach Kurve Bus service, a shuttle that runs for roughly the full 4 km from the town of Nurburg down the racetrack and back again, from 6 A.M. to 7 P.M. My bus driver, Udo Zanzen of nearby Bodenbach, was so popular with the instant community that developed on the Nordschleife that as he made his occasional stops (no formal bus stops mind you, just pickup points wherever two or more banded together and hailed the bus down), it was common for the campers to come up not for a ride but to offer Udo food and drink from the grilles and coolers that dotted the landscape.

Bucknum never won a race for Honda; that honor would go to Richie Ginther, who joined Honda from BRM for the 1965 season and won the Grand Prix of Mexico, the last race of the 1.5 litre formula and the first historic win for two companies that in time would become giants of Grand Prix racing, Honda and Goodyear, the tires the Honda team was running on. Ironically, it is said that the more experienced Ginther, as the No. 1 Honda driver, swapped cars with Bucknum on the morning of the race in Mexico City, so it could have been Bucknum instead of Ginther that brought Honda its first win, which would have been fitting but was not to be.

Bucknum never won a race for Honda; that honor would go to Richie Ginther, who joined Honda from BRM for the 1965 season and won the Grand Prix of Mexico, the last race of the 1.5 litre formula and the first historic win for two companies that in time would become giants of Grand Prix racing, Honda and Goodyear, the tires the Honda team was running on. Ironically, it is said that the more experienced Ginther, as the No. 1 Honda driver, swapped cars with Bucknum on the morning of the race in Mexico City, so it could have been Bucknum instead of Ginther that brought Honda its first win, which would have been fitting but was not to be.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 9, Issue 30

Articles

Interview with Chris Dyer

Rookie at the Ring

Ann Bradshaw: View from the Paddock

2003 British GP Review

2003 British GP Review

Tilting at Tilke

The Arnie Magic

Stats Center

Qualifying Differentials

SuperStats

Charts Center

Columns

Season Strokes

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |