Atlas F1 Technical Writer

With only minor rules changes for 2002, teams generally went in one of two directions this season, developing their existing car, or radically redesigning it. By season's end it was clear both approaches didn't necessarily guarantee success. Craig Scarborough reviews the teams and the cars they raced in 2002 as they attempted to topple Ferrari

Whereas Ferrari won in 2001 with a conventional car that paid careful attention to detail design, the pre-season rumours were about a Ferrari with a radical nose and rear end. From there, and even for the opening races, F1 pundits suggested twin keel noses and exotic gearboxes were the sole way to win in F1 these days. This was oversimplifying the complex design requirements of the F1 car, but was symptomatic of the real needs. Which were creating more efficient downforce and lowering weight, basic ingredients of any racecar's development.

Aerodynamics are crucially important, but there are various philosophies to achieve the desired downforce drag figures the technical directors are seeking. Twin keels are one route, simpler single keels are another, and each are as viable as each other. All the designers are looking for ways to make efficient downforce at the front of the car since the wing's height was raised in 2001. Both the wing's shape and the clearance area behind it are fundamental requirements for creating downforce, but what some teams have discovered is that the interaction with bargeboards and the shape under the raised section of monocoque can add downforce. Only McLaren and Arrows sought real gain in these areas, while other teams simply cleared up the area behind the front wing with twin keels.

Ferrari's radical gearbox was cited as super short, super light and super quick to shift gears. Shift speeds only contribute a small gain to lap times, while a shorter gearbox will affect the weight split front to rear, but generally its length is dictated by wheelbase considerations, but most importantly a lighter gearbox has several gains, less weight means more ballast to tune the car and less weight at the extreme ends of the car improves handling.

Wide angle engines were also a pre-requisite according to the pundits, as the lower centre of gravity improved the car's handling; while this is true, the other factors related to the engine's performance and reliability has disproved this myth.

Electronics continued to advance this year, as the second generation of systems after last year's introduction brought more control and for the first time allowed two-way telemetry, allowing the team to send information and changes to the car, as well as receive information from it.

Ferrari's barrel format enclosed brake ducts were adopted by every team bar McLaren, who retained their twin scoop ducts with a round plate to blank off the inner wheel from the brakes. Several teams (Jordan, Toyota, Minardi) adopted extra ducts passing through the centre of the discs to cool the pistons on the outer side of the caliper.

Exhaust outlets were universally through the top of the sidepods, with McLaren and Minardi finally relenting on their favoured exits through the diffuser. Ferrari's low sidepods left the exhaust pipes covered by a fairing that also acted as the cooling chimney for the radiators - Sauber and Williams adopted a version of this layout for the hotter late season races.

Lastly, the most important element of any team's design has been the person acting at the top of the organisation, often tagged as the technical director. This year saw a huge rise in prominence of these engineers. Gong back to the 80s, John Barnard's name was touted as the best in F1, where previously the big names had been the team owners who sometimes also played a part in the design of the cars, as with Colin Chapman at Lotus. When Adrian Newey came along in the late 80s, and his subsequent departure from Williams to McLaren in the 90s for a driver's level of pay kicked off a pattern that now sees top designers switch teams as much as drivers.

This year several teams produced substandard cars and the named designers in question were held accountable, losing their jobs. Adrian Newey almost left McLaren in 2001, and later that year Geoff Willis left Williams for BAR. This year aero man Ben Agnethalou left Renault for Jaguar, Jordan lost technical director Eghbal Hamidy in a cull of staff, BAR sacked Malcolm Oastler (now with Jaguar), Jaguar split with technical director Steve Nichols and designer John Russell, Arrows separated from Mike Coughlan (now with McLaren) and left name of the year Sergio Rinland without a job when their finances failed.

Team by Team

Ferrari

After the most outrageous claims from every source that the F2002 would be a radical car from front to rear, the car that was unveiled in February was less than expected. While there is no question that Ferrari addressed every aspect of the car's design, first visual impressions proved largely right, that the car was similar along the middle with new sidepods. There is a well-founded rumour that the new car was late not because the radical gearbox was late, but because the initial design was not providing the figures hoped for on computer simulations. This draft version of the F2002 was the version that was said to have twin keels and some other unseen features. This version was abandoned in favour of a more conventional design. The team revised the drooped nose shape but retained the front wing, single keel and bargeboard philosophies. The cockpit and even elements at the rear end remained intact.

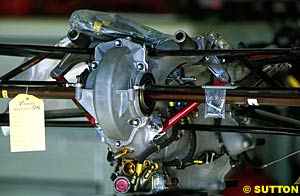

The combined effect of centralising the weight and matching the rear downforce to the already excellent front-end grip of the F2001 gave the Ferrari benign handling that suited all tracks, and left the balance of the grid trailing in their wake. Later in the season the gearbox was cropping up in spy shots and proved to be quite conventional for a frontline team, just as Ross Brawn had said all along. The damper and suspension layout was almost identical to the F2001, only the gearbox casing being in cast titanium and its clean exterior line to add to the aerodynamics were visible changes.

The 051 engine was all new for 2002 and proudly presented at the launch, retaining the Ferrari-led trend for a 90 degree V angle. The motor was soon tipped as the equal of the powerful BMW engine. But Ferrari trumped BMW, if not on outright power, then certainly on delivery and reliability. Drivability, that is the ability for an engine to respond at a wide range of revs, is every driver's desire, and Ferrari appear to have made progress this year, which can be partly attributed to the exhaust layout. The large oval outlets on the Ferrari exhausts are believed to be formed in order to provide a five-into-two layout. This collects the five exhaust pipes each side of the engine into a three and a two 'pair' at the collector. The oval pipe accommodates and hides the resulting pair of pipes and explains the splitter in the pipe's exit.

Bridgestone no doubt contributed tremendously to Ferrari's pace this year, as Ferrari are the only 'A' team supplied by the manufacturer. In order to monopolise on this, Ferrari set up a dedicated test team and pounded test tracks between every race. If the resulting tyres suited the Ferrari more than Bridgestone's other customers, it is only on account of the level of input they provided. Yet it still has to be said the Ferrari was kind to its tyres, not something all recent Ferraris can be credited with. This allowed the team to play with tyre selection and perform well even when hotter conditions compromised the tyre's performance.

With the F2001 comfortably on the pace for the opening races, the new car was another step ahead and as a result did not see a huge amount of development during the year. With flip-ups and winglets added to the launch specification, it took several races before new bargeboards with a saw tooth lip along their lower edges appeared. These directed more of the air flow under the car and produced less of a vortex trailing around and under the sidepods, further improving the downforce at the rear. A one-off appearance of BAR-like nose fins at Imola was inexplicable, but the lowering of the engine cover mid-season and a late season slimming of the area around the gearbox further strengthened the theory that that improving rear grip to match the front was Ferrari's aim this year.

Williams

Pre-season, Williams were tipped as real contenders to Ferrari's crown. The BMW engine was powerful, the Michelin tyres were maturing, and Williams are known to be able to create a top line car. These thoughts changed the instant the car was revealed on a wet Silverstone morning in January. The car appeared identical to its predecessor, which itself was not rated as a cutting-edge design. Some work was done to the bodywork between the rear wheels but little else, the car looking large and inefficient.

In the hotter races, where the Michelin tyres were able to withstand the heat better, Williams shone. The early sidepod design was so efficient at cooling that no chimneys were installed on the Williams, even when the other teams were hastily cutting holes in theirs. This overcooling capacity was admirable, but it suggested aerodynamic and weight gains could be made at the cost of some cooling.

Development of the car got going immediately. By the start of the European season the flat wing was replaced by a curved version, and by Silverstone a major reworking of the aerodynamics led to new sidepods, slimmed to mimic Ferrari with similar winglets. The Silverstone update was part of a package of changes to improves the car's propensity to eat its rear tyres, leading to the McLarens being able to match their race pace for the first time. Electronics and the teams approach to tyre selection were also reviewed.

McLaren

If the new Ferrari was not radical, the new McLaren was a major departure from either their own or anyone else's designs to date. After several successful seasons of similar designs based around the 72 degree Mercedes engine, the potential had gone out of McLaren's package. So a new philosophy was tried which affected every element of the car. Designed around a wider angled Mercedes engine, never confirmed but believed to be over 90 degrees, the new car had a new front end, rear end and tyres.

The car's design was equal with Arrows in its technical interest. The twin keel concept was taken from Sauber and developed into a combined keel and bargeboard. The angled keels formed the first part of the three-layer bargeboard, which followed a similar shape to the previous version McLaren had run. The keels were stiffened by a horizontal strut and aimed to keep the undernose area completely clear of obstruction. The front wing was all-new and used three elements over the more usual two. Further down the car the new engine forced Adrian Newey to place the exhaust exits through the top of the sidepods for the first time, requiring an all-new diffuser design. The gearbox was also new and placed the vertical dampers partially enclosed in the gearbox, operating midway down the damper body, leaving the upper section of the damper exposed for adjustments.

Considering the car had so many problems, there was little visual change to the car during the season; the three element front wing was a permanent fixture, only substituted for fast tracks with a flatter two-plane version and the one-off anhedral wing for Monza. For the last race of the season there was a new gearbox package using the same damper layout but being much lighter, and placing the weight of the brake further forward.

As the team developed the chassis, engine and gearbox, it was only in the late season races that they posed a threat to Williams largely through their better use of tyres in race conditions. In qualifying the tyres were not used as well as the more aggressive Williams and the race starts often saw a slower starting McLaren beaten away by the Renaults.

Renault

Much of the car was carried over from last year, utilising a new version of the wide angle V10. Renault proudly displayed a mock-up of their engine to the crowd at the car's launch, but perhaps the engine was one of the car's downfalls during the season. The R202 was basically a sound and fast car; it did prove difficult to set up to changing tyre and circuit conditions, but when tuned in the car was a match on pace for McLaren.

On the chassis side, constant detail development was the strategy, Renault switched between flat and curved rear wings to gain rear grip, and front wings and bargeboards were altered on a race-by-race basis. Mid-season a major revision to the sidepods saw new flip-ups and cooling outlets, and though the impact of these was not immense, yet they remained on the car until the season's end.

Sauber

The 2002 car retained the short twin keels and the unique low line diffuser, despite many tests with a fully walled version. Bargeboard and front wing design were played with to match circuit characteristics, but the car never veered far from its early season specification. At a few races the team were totally lost on set-up despite the experience of people within the team. The car's reliable Ferrari-sourced engine proved to be the team's biggest asset and provided consistent power and reliability.

Jordan

Initially almost incurable problems with the gearbox plagued early tests and then the Honda engine's power stymied pace. The car seemed to handle well, and as with most of Bridgestone's customer teams, needed the tyres to match the car and circuit. Development during the season was limited, as the original designer had parted with the company after being accused of producing a car that was too risky and even may have broken some dimensional rules. Returning to the Jordan fold was Gary Anderson who worked with the race team in a productive manner to get the best out of the car. As the season progressed so did the car's handling to be right up with Renault at the season's close.

Jaguar

Like Jordan, Jaguar hit the trends for aero design right on the head, with the highly raised nose sporting a hybrid single/twin keel layout, its drooped nose sporting a fashionable triple element front wing. The rear end was less trendy, but well-proven, with Cosworth's latest 72-degree engine matched to a conventional coil-sprung multi-link rear end. The sidepods mimicked the previous year's design, and as with Jordan, soon appeared dated.

Instantly the experienced technical director Steve Nichols quit the team and the rest of the design team's jobs were in jeopardy as new staff were drafted in: Gunther Steiner from the Ford rally team, and Ben Agnethalou from Renault's aerodynamic department. New rear suspension replaced two of the links with a wishbone, and new stiffer uprights were cast. By Silverstone the new aero update was ready and hailed as the cure-all for the R3; a simpler front wing, endplates and bargeboards were added; the floor was also revised, and high speed handling improvements were found, but the car was still less than perfect. Later in the season yet more suspension revisions front and rear were adopted, but despite two good results, the car was rightly blamed as a poor initial design.

Ford's Cosworth engine, with its special cylinder heads, proved powerful enough for the midfield, and was quite reliable. Development picked up late in the season with several steps introduced to boost qualifying pace. However the car was never in harmony with its Michelin tyres except in hotter races, where the temperature got the tyres up to temperature.

BAR

After several seasons of indifferent cars and poor reliability, BAR's outlook did not look good. Then when Honda announced they would provide major technical input for the new car, things looked rosy, as Honda's input went beyond the engine to include the gearbox, aero, chassis and structures.

New on the car was the lowline Honda engine which BAR chose to mount to the chassis via a reinforced airbox to increase installation stiffness, whereas Jordan never thought the weight this added high up was necessary for the engine. The team was now managed by David Richards, and he brought some of his staff from Prodrive to review the operation, finding BAR was behind in many areas of design and production. After a few races with poor performances, Oastler was returned to Reynard where he had come from and ex-Williams aero man Geoff Willis was elevated from BAR's 'head of aero' to technical director. Many other staff were ejected as the new team manager sought to revive the team.

The car was lacking pace and suffered chronic gearbox and particularly clutch problems. Willis went to work, restructuring the design department as well as working on a 'B' version of the car. The car was rolled out in Canada, where the new bodywork bore a remarkable resemblance to the Williams he'd been designing for several seasons previously. Forward low-mounted bargeboards were matched to a full-width fin across the front of the sidepods, lower and larger flip-ups were installed on the sidepod's flanks and chimneys were used as extra cooling outlets. The front wing and endplates remained unchanged throughout the year, although tests with a flat version were tried earlier in the season.

BAR's pace did pick up, and reliability problems with the gearbox and chassis were solved. The engine was still a weak point, but Honda's rate of development with its new engine was incredible through the year - by mid-season, new qualifying versions were at most races, and these were then quickly elevated to race engines. Reliability was still poor however, and when the engine went, it tended to go in a big way.

Minardi

The pioneering cast titanium gearbox was further developed and used more conventional anti-roll bars. With a good basis for the car, it was then starved of development. Limited wind tunnel and track time brought a few advances; triple flip-ups on the sidepods and detail revisions to the front wing and brake ducts were seen during the season but did not make an impact on the team's pace in comparison to the pack ahead of the them.

Toyota

Their test car that ran throughout 2001 was slated as a poor performer, but it was designed purely as a test bed. Then the late firing and hiring of designers left Toyota with little time to develop their debut car as far as they would have liked. Simple and reliable were the key aims of the TF102. The resulting neat, if a little chunky, car looked outwardly conventional and never suggested that anything but midfield placings would be expected.

Yet the ingredients fell short so often this year. Top ten qualifying was common for just one car, and then in the race the cars fell away to the rear of the midfield and niggles pulled the cars into retirement too often. The car also hated to put its immense power down or run over kerbs, suggesting the lowline rear damper set-up was not compliant enough. Aerodynamically the car was starved of development quite early in the season as work centred on the new car for 2003. Front wings, bargeboards and cooling outlets were only altered in detail. There was an unexpected overhaul in the last two races where Williams-esque bargeboards and sidepod fins were piloted, suggesting Gustav has some plans for the new car, most likely in the adoption of Arrows-like twin keels blended in with these new bargeboards.

Arrows

The keels extended all the way to the floor of the car, and evacuated air from under the nose, routing it around the conventional bargeboards in front of the sidepods. The lower edge of the keel extensions initially had a flat lip; with testing this was soon replaced by a ramped diffuser, creating even more downforce. These keel extensions when added to a curved front wing probably gave Arrows the scope for the most front-end downforce on the grid, yet the car's development was halted by funds and the low-spec Ford engine. Further down the car, the design was still quite radical, as the narrow angle engine was mated to a lightweight carbon fibre gearbox, while the radiators fed hot air out of the sidepods through sculpted ducts.

Overall this was the car that will need copying more than almost any other car from 2002.

Technical direction in 2002 went several ways, despite very few rules changes that were supposed to encourage consistency in pace and design. Instead, what we found was design departments with more time to analyse the fuller impact of the front wing rule changes from 2001. This year saw the diversification of bargeboards, suspension and engine layouts, yet the almost standardisation of brake ducts, front wings and exhaust outlets.

Attention was drawn away from the sidepods as pundits speculated on the gearbox. What Ferrari had done was to improve the cooling capacity of the car and moved yet more weight forward to the middle of the car. The new radiators were installed at a complex compound angle, the resulting shape maximising the surface area of the radiators and kept the sidepods slim. The radiators also sported filters placed in front of the cooling surface. It could be that the radiators use thinner cores to improve cooling and are more prone to damage, for this would explain Ferrari's pit crew using vacuum cleaners to clean the sidepods out at 'dirtier' race tracks. Regardless, the forward-mounted radiators allowed the sidepods to tuck in lower and tighter than any other car on the grid, improving flow over the floor and to the rear wing.

Attention was drawn away from the sidepods as pundits speculated on the gearbox. What Ferrari had done was to improve the cooling capacity of the car and moved yet more weight forward to the middle of the car. The new radiators were installed at a complex compound angle, the resulting shape maximising the surface area of the radiators and kept the sidepods slim. The radiators also sported filters placed in front of the cooling surface. It could be that the radiators use thinner cores to improve cooling and are more prone to damage, for this would explain Ferrari's pit crew using vacuum cleaners to clean the sidepods out at 'dirtier' race tracks. Regardless, the forward-mounted radiators allowed the sidepods to tuck in lower and tighter than any other car on the grid, improving flow over the floor and to the rear wing.

The design team were sure the right level of gains had been made, but after its first race it was clear these gains were not large enough. The car still had a cumbersome single keel and a flat front wing, it lacked downforce. BMW had made leaps with the engine, still with a 90 degree layout carried over from 2001. By season's end it reached 19,000rpm and an estimated power output of just under 900 bhp. Though the engine's reliability was not great, usually one car could be expected to complete the race distance.

The design team were sure the right level of gains had been made, but after its first race it was clear these gains were not large enough. The car still had a cumbersome single keel and a flat front wing, it lacked downforce. BMW had made leaps with the engine, still with a 90 degree layout carried over from 2001. By season's end it reached 19,000rpm and an estimated power output of just under 900 bhp. Though the engine's reliability was not great, usually one car could be expected to complete the race distance.

With all these elements being introduced in between two seasons with a two month testing ban, McLaren's resources were being overstretched. Pre-season testing looked promising, the car lapping Barcelona in ever quicker times, but come Australia, the car was clearly outpaced by Ferrari and Williams. There was not just one area to point the blame at - the engine was down on power and unreliable, the team could not match a set up with the tyres, and there were gearbox gremlins. There was not panic and incrimination at McLaren as there was at other teams; instead, the team diligently went about testing and development to cure their problems.

With all these elements being introduced in between two seasons with a two month testing ban, McLaren's resources were being overstretched. Pre-season testing looked promising, the car lapping Barcelona in ever quicker times, but come Australia, the car was clearly outpaced by Ferrari and Williams. There was not just one area to point the blame at - the engine was down on power and unreliable, the team could not match a set up with the tyres, and there were gearbox gremlins. There was not panic and incrimination at McLaren as there was at other teams; instead, the team diligently went about testing and development to cure their problems.

Yet many race finishes were robbed most cruelly by late race engine failures. Engine failures also accounted for a lot of lost time during practice sessions. With such poor reliability, power outputs suffered and the Renault had little to back up its innate handling qualities. Progress was made during the season, but the vibration and the powersapping poor airbox shape from the wider engine angle will probably result in this format of engines being pulled from F1.

Yet many race finishes were robbed most cruelly by late race engine failures. Engine failures also accounted for a lot of lost time during practice sessions. With such poor reliability, power outputs suffered and the Renault had little to back up its innate handling qualities. Progress was made during the season, but the vibration and the powersapping poor airbox shape from the wider engine angle will probably result in this format of engines being pulled from F1.

Another almost unchanged car, utterly conventional and solidly reliable, yet always near the pace, though it has to be said Sauber needed the Bridgestone tyres to be on form to get the best out of the car and to beat Renault. After an encouraging year in 2001 and a good start to the 2002 season, the team fell back into the habit of not developing the car.

Another almost unchanged car, utterly conventional and solidly reliable, yet always near the pace, though it has to be said Sauber needed the Bridgestone tyres to be on form to get the best out of the car and to beat Renault. After an encouraging year in 2001 and a good start to the 2002 season, the team fell back into the habit of not developing the car.

When the EJ12 was released, it looked like Jordan had pinpointed all the design trends for 2002 perfectly, and allied to the new lowline Honda engine, it suggested the new car might fly. The 'anteater' nose with twin keels was matched to closely mounted bargeboards, though later paired with a curved 'spoon' front wing that discarded the Jordan trademark stepped wing, but not before a totally flat wing was trialled. Cooling outlets consisted of chimneys that were frequently run closed off to control overcooling, while the other trademark, the winglet/flip-up was retained by Jordan all year and started to appear dated by season end.

When the EJ12 was released, it looked like Jordan had pinpointed all the design trends for 2002 perfectly, and allied to the new lowline Honda engine, it suggested the new car might fly. The 'anteater' nose with twin keels was matched to closely mounted bargeboards, though later paired with a curved 'spoon' front wing that discarded the Jordan trademark stepped wing, but not before a totally flat wing was trialled. Cooling outlets consisted of chimneys that were frequently run closed off to control overcooling, while the other trademark, the winglet/flip-up was retained by Jordan all year and started to appear dated by season end.

As soon as the car ran it was obvious there was something amiss. In the panic fingers pointed everywhere at the car. It was later quite clear most of the fingers pointed accurately, such was the scale of the problems. The front wing was not rigid enough, it did not produce enough downforce, and it upset flow under the car. Both the wishbones and uprights were not rigid enough; the brake calipers were mounted high and upset the centre of gravity.

As soon as the car ran it was obvious there was something amiss. In the panic fingers pointed everywhere at the car. It was later quite clear most of the fingers pointed accurately, such was the scale of the problems. The front wing was not rigid enough, it did not produce enough downforce, and it upset flow under the car. Both the wishbones and uprights were not rigid enough; the brake calipers were mounted high and upset the centre of gravity.

The new car was rolled out late in 2001; it looked almost identical to the model that had just completed the season's last race in Japan. Designer Malcolm Oastler insisted it was a major leap for the team in every area, yet many of the car's key design philosophies remained unchanged. The mid placement of the steering rack, the aero layout and even the all-new gearbox retained a similar suspension layout.

The new car was rolled out late in 2001; it looked almost identical to the model that had just completed the season's last race in Japan. Designer Malcolm Oastler insisted it was a major leap for the team in every area, yet many of the car's key design philosophies remained unchanged. The mid placement of the steering rack, the aero layout and even the all-new gearbox retained a similar suspension layout.

As the first full F1 design for Gabriele Tredozi, after Brunner's departure for Toyota in 2001, the car was a sound proposition. Adopting a higher nose and pushrod suspension, with the steering link inline with the top wishbone, the car looked conventional. The engine was now supplied by Asiatech, the 72 degree unit being totally revised from the unit supplied to Arrows in 2001. The new engine forced Gabriele to discard his favoured low exhaust exits for periscope-format versions.

As the first full F1 design for Gabriele Tredozi, after Brunner's departure for Toyota in 2001, the car was a sound proposition. Adopting a higher nose and pushrod suspension, with the steering link inline with the top wishbone, the car looked conventional. The engine was now supplied by Asiatech, the 72 degree unit being totally revised from the unit supplied to Arrows in 2001. The new engine forced Gabriele to discard his favoured low exhaust exits for periscope-format versions.

Under the skin there were many special touches, chassis designer Gustav Brunner creating a unique low-placed rear suspension set-up, using Sachs latest pullthrough dampers placed outside the gearbox and pulled in tension, rather than compressed as is conventional. The 90 degree V10 engine was also something very special, with a lot of ex-Ferrari staff on the project. The engine was soon rated as one of the top four for power output and never displayed the explosive unreliability characteristics of some of its competitors.

Under the skin there were many special touches, chassis designer Gustav Brunner creating a unique low-placed rear suspension set-up, using Sachs latest pullthrough dampers placed outside the gearbox and pulled in tension, rather than compressed as is conventional. The 90 degree V10 engine was also something very special, with a lot of ex-Ferrari staff on the project. The engine was soon rated as one of the top four for power output and never displayed the explosive unreliability characteristics of some of its competitors.

Although the Arrows never made it to the end of the season, and never shone greatly in the races it attended, the design should be rated as one of the most interesting cars of the year. Eschewing the trend for low drooped noses and short simple keels, the Arrows adopted a very high monocoque, with twin short structural keels to mount the lower wishbone. When stripped of bodywork this appeared quite an innocuous set up, but with bargeboards and nosecone fitted, the full purpose of the design was clear.

Although the Arrows never made it to the end of the season, and never shone greatly in the races it attended, the design should be rated as one of the most interesting cars of the year. Eschewing the trend for low drooped noses and short simple keels, the Arrows adopted a very high monocoque, with twin short structural keels to mount the lower wishbone. When stripped of bodywork this appeared quite an innocuous set up, but with bargeboards and nosecone fitted, the full purpose of the design was clear.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 8, Issue 43

Atlas F1 Exclusive

Max Mosley on the F1 Crisis

Is the Sky Falling?

Jo Ramirez: a Racing Man

2002 Season Review

The 2002 Race-by-Race Review

The 2002 Drivers Review

The 2002 Teams Review

The 2002 Technical Review

The Atlas F1 Top Ten

The 2002 Trivia Quiz

Columns

Bookworm Critique

Elsewhere in Racing

The Grapevine

> Homepage |