Atlas F1 Magazine Writer

Amid the stir caused by the controversial proposals presented to bring the excitement back to Formula One, Michael Schumacher continued with his flawless year and scored yet another dominant victory at the season-ending Japanese Grand Prix. But the German was overshadowed by an emotional fifth place from Takuma Sato. As the powers-that-be look set to change the face of F1, Richard Barnes warns them not to forget that the human side is still the most important part of the sport

It also helped that Schumacher was not tested to the limit, either by teammate or foe, for the greater part of the season. Still, even for a driver who only allows himself one major driving error per season, that level of consistency sets a new historical benchmark that will stand for years. Providing, of course, that Byrne's 2003 offering doesn't raise the Ferrari bar by another notch...

It's a prospect that has caused growing anxiety among the F1 establishment. During the golden era of classical Grand Prix racing, the most fearful sound was the impact of rubber and metal into Armco or concrete. Nowadays, it's the clicking of a million remote controls as television viewers seek their vicarious thrills elsewhere. The mooted solutions to the entertainment crisis, from weight handicaps to 'musical chairs' parlour games for the drivers, are simply absurd. If Formula One is to remain the pinnacle of world single-seater motor sports, then the laws of merit must prevail. If an unmerited win handed to a driver by his teammate is unsatisfactory, then even more so a victory granted by weight penalties to faster cars.

Amidst the divergence of opinions, McLaren chief Ron Dennis has emerged as a notable voice of reason. Dennis recalls the dynamic all too well from the late 1980s, when his red-and-white MP4-4s of Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna swept all before them. At the time, Dennis deflected complaints of McLaren's dominance by stating that it wasn't his team's job to go slower, the onus was on the opposition to go faster. Dennis himself is now in the position of having to improve his team's performance in order to win, and his views have remained consistent.

Quite how Ferrari's rivals are going to achieve that remains a mystery. The McLaren and Williams domination of the mid-1980s to early 1990s was tied inextricably to the vagaries of major manufacturer engine programmes. When the dominant engine manufacturer achieved its goals and withdrew, change was guaranteed. With most of the major manufacturers already committed to at least medium-term team partnerships, that avenue has been effectively sealed.

Going slightly further back in history, innovation was the great leveller. It was impossible for one team to research and test every innovation possible, which again allowed for greater competition. With the innovation envelope narrowed to the barest sliver by current regulations, it seems that yet more legislation in an already over-regulated sport is not going to provide a satisfactory solution. Money will not provide answers either. Even when viewership and revenues have been at an all-time high, the privateer teams have been battling to survive economically.

Instead, the sport needs to examine its place and aims, and decide what it wants to be. For currently, F1's biggest problem is that it wants to be all things to all people. It wants to be a home for both major manufacturers and privateers. It wants to give mass-market manufacturers a showcase for technological superiority - just as long as they don't dominate too much or for too long. It wants to give fans close racing - then passes legislation that almost prohibits overtaking. It wants to be both a team and an individual sport. It wants the global variety of races at a variety of circuits in different countries - provided they consist of 60-70 laps and fit neatly into a two-hour telecast. Formula One cannot simultaneously be a sport, a business and showbusiness, for the aims of each are at odds with the others.

In seeking solutions to the current dilemma, one needs look no further than the hero of Sunday's Japanese Grand Prix. Michael Schumacher may have dominated the race, and Ferrari may have wrapped up an awe-inspiring season with their customary professionalism, speed and reliability. But, for all that, it was a curiously emotionless and soulless performance, from a team that is traditionally more passionate about racing than any other. In terms of emotional impact, the true hero of Suzuka was Japan's own Takuma Sato.

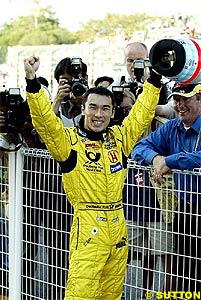

Ritually outperformed by his vastly experienced and talented teammate Giancarlo Fisichella over the course of the season, and with a record of destroying way too many cars even for a rookie, Sato arrived at Suzuka as a troubled man with limited future prospects. By late Sunday afternoon, he'd been transformed into national hero and Jordan saviour.

The task of earning the Championship points required by Jordan to elevate them up in the Constructors' Championship standings seemed too steep during Sato's early scrapping with the Renault pairing of Jarno Trulli and Jenson Button. Surely Sato's nerve wouldn't hold, and he'd end up in the barriers or, like Fisichella, with another blown Honda engine? Thankfully, neither Sato nor his Jordan Honda had read the script. When he crossed the finish line to the wild acclaim of the fans and his own Japanese flag-bedecked pit crew, he not only did his team a huge favour, but turned an otherwise ordinary Grand Prix finish into a memorable one.

There are no carefully primed PR team statements that can compete with the unbridled and totally spontaneous joy of Sato and his crew. There is no amount of corporate showcasing that can enthrall a crowd so completely, and there are no statistics that can warm the heart like Sato's performance did on Sunday. Even at the technological pinnacle of motor sport, the appeal was, is and will always be the human triumph over adversity - even when that triumph gleans only two points instead of ten. It's the human touch. And when the sport's establishment get together on October 28th to discuss the sport's future, they'd do well to bear that in mind.

Sunday's Japanese Grand Prix confirmed what, for decades, had been deemed unthinkable - one driver not only finishing every race of the 17 Grand Prix season, but doing so on the podium each time. As soon as fantasy had been turned into historical fact, Michael Schumacher was the first to heap praise on his employer Ferrari for the team's magnificent reliability record during 2002. But the oft-forgotten aspect of Schumacher's astounding season is that a bullet-proof car isn't enough, the driver must also pilot it safely to the finish.

In a sport in which the margins are so tiny and so crucial, that is no mean feat. Schumacher's new record involved 1090 laps covering 5,174 kilometres of track at racing speed - without a single race-ending error. Naturally, it helped that Rory Byrne's F2002 not only lasted the distance without a hiccup, but was also an obedient beast that went where it was pointed and did what it was told. The lack of driver activity from Schumacher's in-car shots was a marked contrast to the constant driver corrections required by the mid-90's Benettons in which the German aced his first two WDC titles.

In a sport in which the margins are so tiny and so crucial, that is no mean feat. Schumacher's new record involved 1090 laps covering 5,174 kilometres of track at racing speed - without a single race-ending error. Naturally, it helped that Rory Byrne's F2002 not only lasted the distance without a hiccup, but was also an obedient beast that went where it was pointed and did what it was told. The lack of driver activity from Schumacher's in-car shots was a marked contrast to the constant driver corrections required by the mid-90's Benettons in which the German aced his first two WDC titles.

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 8, Issue 42

Atlas F1 Exclusive

Exclusive Interview with Rory Byrne

Ann Bradshaw: View from the Paddock

Japanese GP Review

2002 Japanese GP Review

Japanese GP Technical Review

Bridgestone: The Shining Quarter

The Human Touch

Stats Center

Qualifying Differentials

SuperStats

Charts Center

Columns

Season Strokes

Elsewhere in Racing

The Grapevine

> Homepage |