with Dickie Stanford

Atlas F1 GP Correspondent

Dickie Stanford is one of the longest serving team managers at WilliamsF1, and not without reason. Working his way from gearbox mechanic to Nigel Mansell in 1985, the thoughtful Briton has made a name for himself as one of the most professional, knowledgeable and amicable workers in Formula One. He has worked with five World Champions; he's seen his team at the very low and in their highest form. Jane Nottage hears from him about the difference between the drivers - past and present, about the good days and the bad ones; and just why he won't ever leave Williams for another team. Exclusive for Atlas F1

And Stanford - a familiar face in the paddock even if less so to the casual fans - has been with Williams for a long time.

A 1950s wild child, Stanford has the appearance of a successful and studious college professor rather than a racer at heart. Quiet and thoughtful, he rules with calm authority in a job that has seen his predecessors come and go on an almost regular basis. Being team manager is a tough job: he co-ordinates all of the team's activities - from testing, to moving the equipment across countries and continents, to liaising with the FIA. And Stanford has been doing the job for eight years now, having been with the team for 17 years altogether.

No one survives with team owners Frank Williams and Patrick Head for that long by being a pushover, and no one gains their respect and works up through the ranks from mechanic to team manager without talent and ruthlessness. Stanford has them both.

Take Monaco, for example. The place is not only difficult for the drivers to conquer, it's also one of the worst logistical nightmares for Stanford and his crew. The tight Paddock, full of hidden passages and doors, is like a medieval castle. It is so tight, in fact, that it looks as if a child has had a tantrum with the motorhomes and just chucked them down and left them where they land. "I had a bit of a moment in 2000, when a mix-up of measurements meant we couldn't fit in the Paddock," Stanford recalls. "So I said, 'right, that's it. We're going up to Alcatraz and we'll find a corner to park up there.'"

Alcatraz is the multi storey car park at the top of a steep slope on top of the paddock. It is where the smaller teams are sent to work, and working from there means the cars have to be pushed up and down to the pits - a drag over a long weekend. But Stanford made it work.

That was the year I found him sitting on his scooter in the car park, drinking a can of coke and musing about life and missing his daughter's birthday yet again. "My family put up with a lot," he says today, when reminded of that occasion. "Even when I'm going into the office I leave home at 8:00 am and don't get home until 9:45 pm. I can't remember the last time I left at 5:00 or 6:00 pm, and I think I've only made it home once for either of my daughters' birthdays."

The long hours are in part due to the fact that the end of the day is the best time for Stanford to sit down and mull over things with team boss Frank Williams, who remains very much hands on with the team and wants to know every small detail. Stanford is, in many ways, Williams's eyes and ears within the team, and whether it's an anecdote about a driver or a real problem with the car - Stanford will be the first to report to Williams about it.

* * *

Born near Swindon, Wiltshire - about 90 miles west of London - Stanford got involved in motor racing quite accidentally.

While working as a garage mechanic, he used to pass right by the front door of the Williams Grand Prix team, which was located down the M4 in Didcot, not too far from Reading in Berkshire. One day, as he was passing by, he thought 'oh well, why not give it a shot and apply for a job.' Without any real experience in the top formulae, Stanford wandered into the reception area and waited a while before then team manager Peter Collins came out to find out who this guy was with enough cheek to appear out of nowhere and ask for a job.

The year was 1983, and because of his lack of experience Stanford didn't get a job, although he made an impression. "I was impressed with him as I thought he showed initiative and commitment in wanting to work for us," Collins, living now in Switzerland, recalls. "But he didn't have the right experience, and so I told him to go away and get experience in Formula Two and then come back."

Stanford took this to heart, and went to work for Ralt, a Formula Two team, but his heart was still on Williams and two years later, in 1985, his dream came true. Once again it was more by chance than by design. "I knew someone at Ralt who knew Alan Challis - the then Chief Mechanic at Williams - and so I asked him if he could set up an interview," Stanford says. "Anyway, one day I was taking the wind tunnel model from Ralt to Williams so we could use their wind tunnel, and when I dropped the model off I got an interview and got the job - it was as simple as that!

"It was the right time [to move to Williams]," Stanford continues, "as they were just going from two mechanics to three mechanics per car, and all the Honda people working at Ralt Formula Two moved to Williams for the Formula One project. I already knew all the Honda people so that was another thing in my favour."

Stanford started off as a gearbox mechanic, working on Nigel Mansell's car. He then moved to the engine; number one on the T-car; and then - as he says - "I decided I wanted to go testing so I went as number one mechanic on the test team in 1988 and 1989, and at the end of the year Patrick (Head) offered me the job of chief mechanic on the race team, so in 1990 I became chief mechanic."

The start of his career in the Grove-based outfit was, by all accounts, a memorable one. Stanford was a mechanic on Nigel Mansell's car, in the Briton's first season with the team, and the two new boys clicked immediately. "I got on very well with Nigel," Stanford says. "He never comes over as well on television as he does in real life, but I would say he was one of my favourite drivers. I never had a problem with Nigel - he was always straight to work with, as straight as a die."

There was another important aspect to the instant bonding between Stanford and Mansell: both men quickly revealed themselves to be team players. "From the team bonding point of view, Nigel was the best driver," Stanford confirms. "It didn't matter what you were doing - you had his attention. You had one hundred and ten percent of him whether you were on the racing side or the technical side; he gave everything all of the time. Normally, if Nigel said the car was rubbish, then the car was rubbish. But once you got it to his liking, he was very quick."

Stanford and Mansell have been through tough times and happy times together. Take the 1986 Australian Grand Prix, for example: to this day, Stanford recalls with agony the final round of the World Championship, where Mansell was on his way to wrapping up his first title when a tyre on his car exploded and forced him to retire. "We were just cruising around and we were well within it to win the Championship and we had all the ingredients - quick driver, quick car and a reliable car, and then it all went pear shaped and Alain Prost took it and we were left with second place.

"It took a long time to recover from that disappointment," he says today. "Fortunately, we had the winter to get over it."

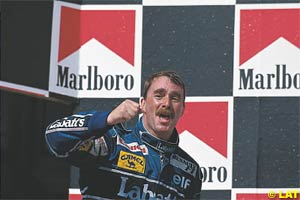

But the two Britons also shared the good times of the Williams domination in the early 1990s, when Mansell wrapped up one of the most convincing Championship challenges ever, in the 1992 season.

Mansell returned to Williams in 1991, after a two-year spell at Ferrari. He won five races in 1991, losing the Championship to Ayrton Senna, but then came back in the next year with a vengeance.

"In 1992 it all came together," Stanford says. "The car was fantastic; Nigel didn't hang around; and we had it sewn up by Hungary." What a succinct way to sum up a year he himself describes as "the best year of my Formula One career"!

Mansell won nine of the sixteen races that season - a record number - and on 16th August 1992, just eight days after his 39th birthday, he pulled off the grand coup and won the World Championship. But the celebrations in the Williams camp were short lived.

"At Williams, as soon as one race is over you're onto the next," Stanford explains. "You park the race good or bad and move on, and concentrate on what's to be done next. I remember there was a lot of champagne floating round the garage [in 1992], but then it was over and we were concentrating on Spa, which was the next race. There was a team dinner at Spa but that wasn't too big a celebration as we had to work the next day.

* * *

Ian Harrison, the then Williams team manager, quit Formula One at the end of the 1994 season, and Stanford was appointed to the job. It is the position that against the odds he still holds today.

"The guys used to give me stick every couple of years, as there used to be a two-year turnover of team managers, so every couple of years a lot of people started shaking their heads and saying 'well, we'll see you somewhere else then.'" But Stanford stuck it out and, as he says, "a stable team is a successful team. It takes time to build a relationship and if you get too much movement within the team then you don't work well together. It's much better to be in the same position for five, six or even seven years and really build up the team. We don't have so much of a turnover compared to other teams."

In his new role, Stanford had the chance to work with yet another compatriot champion. Damon Hill was very different to Mansell, or as Stanford recalls: "Nigel knew exactly what he wanted whereas Damon worked really hard to understand what he wanted. Damon didn't have Nigel's natural talent and the pure speed of the best racing drivers, but he worked hard to get there, he really spent an awful lot of time working at getting there. He worked hard at knowing what he had to do to make the car quick, and also what he had to do to make it quick at the start of practice, qualifying or the race. He had to work hard to get it quick out of the box."

Stanford gives credit to Hill for "going away after he lost the Championship to Michael Schumacher in 1995 and coming back much more serious than in previous years." Likewise, he gives credit to Hill's 1996 teammate Jacques Villeneuve, stating that "Jacques was quick; when he was in the car and it was quick, you'd know that it was on the limit." And, like anyone else who worked with Ayrton Senna, the Brazilian remains one of his all-time racing idols.

"Senna was one of the all time greats, in and out of the car," Stanford says with conviction. "He had the most outstanding mental capacity for feedback - the best I've ever seen in any driver. He was precise and accurate and could hold information in his head that other drivers would struggle with. He also had this incredible ability to focus on the job at hand, and just know what had to be done to make the car go quicker. He was also of course blessed with an outstanding natural talent. For the short time we had him, he was a joy to work with; one of the true greats."

On the other hand, a driver he feels has remained an enigma was Alain Prost, the four times World Champion, who won his final title with Williams in 1993. "Alain was quick but you never knew just how quick he really is, as he always did just what he needed to do and not a bit more," Stanford explains. "He'd do just enough to put the car on pole or be as quick as he needed to be but you never knew how fast he was."

Present drivers are 'hothead' Juan Pablo Montoya and 'cool' Ralf Schumacher, who - Stanford says - are as different in their approach to the team as they are in cultural terms. "Montoya is very similar to the way Nigel was: he comes in and talks to everyone and wanders about getting to know who is who and what is what in the factory, whereas Ralf is much shyer.

Speaking of the young Schumacher, Stanford's arguably most embarrassing moment came last season, when his German driver was left hanging in the air on the Spa grid at the start of the Belgian Grand Prix.

After a massive accident involving Prost driver Luciano Burti and Jaguar driver Eddie Irvine, the cars came back to the grid for a restart, when the Williams mechanics noticed damage to Ralf's rear wing. "Patrick made a decision to change the rear wing as we didn't know if it was a heat related problem or a structural failure, and we couldn't risk an accident," Stanford recalls.

"I then made a calculation and found out we would be running out of time and still be working on the car after the 15-seconds time limit. To the world it looked like we'd started the car and left it in the air, but of course a car won't start if it is in the air, so that was that."

And what about Ralf, what did he have to say about being left in the air? "There's been a lot said of course as team manager getting things on time is my job, but I really can't remember what Ralf said. However, when Patrick explained the situation to him and I explained that if we had carried on working on the car we would have got a ten second stop and go penalty, then he understood. He knows the 15-second rule is there for the safety of the mechanics, and it is much more important than the penalty."

Williams drivers generally find their understanding of the situation increases when faced with the implacable Patrick Head, a man who doesn't take fools easily, and Ralf clearly knew when to shut up and get on with life, although as Stanford says: "with Ralf being a German driver and one half of the famous Schumacher brothers I am very famous in Germany, and let's just say I won't be going on holiday there for a few years!"

* * *

Times have changed since Stanford first joined Williams, and motor racing in the 21st century is very different to what it used to be two decades ago. Stanford doesn't necessarily like the change.

"When I first came into Formula One, the mechanic used to tell the electrician when he could work on the car. Now you've got the electrician telling the mechanic when he can do the next thing on the car. Everything is electronic," he bemoans. "If it makes the car go quicker then we're going to have it, just like all the other top contenders."

If it was up to him, Stanford would have a few rules reversed. "I'd go back to slick tyres," he exclaims - probably to the joy of many agreeing fans. "I really don't know that grooved tyres make that much difference. In spite of the attempt to slow the cars down we're now back to the lap times of four or five years ago as we have a tyre war between Bridgestone and Michelin and so that makes the car faster.

"I think it would be better to either make a harder tyre or, even better, a softer tyre that can only do so many laps - say 15 or 20, and so you'd have to do several tyre stops which would be entertaining for the public.

Speaking of tyres, Stanford says he is happy with Michelin and the progress the tyre company is making. "Michelin is getting there. It was never going to come in and win straight away, as Bridgestone has been around so long, but they are pushing Bridgestone to the limit and getting there very fast."

Along with Michelin, there is also the scent of renewed victory in the team. "We are challenging Ferrari for the Constructors' Championship and that is the one that means more to Williams than anything," Stanford says. "In practical terms, it also means we have more space to work in during the following year as the Champion team has the biggest garage. I'd like to think we can stop Ferrari, both our drivers have proved they can beat Michael. We just need to take another step forward."

But more than anything, Stanford would like to see his boss Frank Williams reign supreme, just like he did ten years ago. In fact, Stanford admits to admiring Williams more and more as time goes by. "How many other team owners up and down the pitlane know everyone's name in the factory?" he exclaims. "I know that Frank goes round and talks to every single person in the factory. If Frank sees someone new he wants to know their name and he never forgets it."

Williams is no doubt one of the reasons why Stanford will remain where he is for the rest of his time in Formula One. "I've had other offers," he reveals, "but I've never seen any reason to leave. The partnership between Frank and Patrick is special and I'm more than happy where I am."

And so, with the passion for winning still coursing through their veins, it won't be long before Williams will be adding another trophy to their already full cabinet, and Stanford will be celebrating in his own low key way. But there will always be a gap in his winners' tally until he can add that elusive Monaco win to the rest of the victories.

Williams team manager Dickie Stanford has seen it all. He was responsible for the decision to leave Ralf Schumacher's car on jacks at the start of last year's Belgian Grand Prix; he was there to solace Nigel Mansell for the loss of the 1986 World Championship, and then to celebrate with him the dominant win of the 1992 crown; he worked with some of the biggest talents of the sport, and he's seen the team in their high and in their lows. And yet, Williams team manager Dickie Stanford has yet to see his team win in Monaco.

"This place is my 'number 13' in motor racing," he says with visible indignation. "My last ambition is to win Monaco. We've had pole position, been second on the grid, led the race and then the car has broken down. But we've never won it since I've been with Williams."

"This place is my 'number 13' in motor racing," he says with visible indignation. "My last ambition is to win Monaco. We've had pole position, been second on the grid, led the race and then the car has broken down. But we've never won it since I've been with Williams."

Working for the Ministry of Agriculture, he was influenced by a Scottish neighbour who was a big Jim Clark fan, and as a hobby began helping a friend in running a Formula Ford. He took interest in the mechanical aspect of running the cars, and soon enough quit his civil servant position to pursue a full-time automotive career.

Working for the Ministry of Agriculture, he was influenced by a Scottish neighbour who was a big Jim Clark fan, and as a hobby began helping a friend in running a Formula Ford. He took interest in the mechanical aspect of running the cars, and soon enough quit his civil servant position to pursue a full-time automotive career.

It also helped that Mansell made time for everyone. "Nigel was probably one of the nicest people I've ever worked for. Every single day, if he was at the circuit, he'd come in and talk to everyone in the garage. He'd even talk to the guys working on his teammate's car - he made sure he spoke to everyone, he'd always say 'good morning' and 'good night' and have a chat with them during the day as well. He was very good at creating team spirit."

It also helped that Mansell made time for everyone. "Nigel was probably one of the nicest people I've ever worked for. Every single day, if he was at the circuit, he'd come in and talk to everyone in the garage. He'd even talk to the guys working on his teammate's car - he made sure he spoke to everyone, he'd always say 'good morning' and 'good night' and have a chat with them during the day as well. He was very good at creating team spirit."

"It's funny, because when Jacques Villeneuve won in 1997 at the last race in Jerez, that was one hell of a celebration - I left the party at 4:00 am and I don't drink! Yet when Nigel won, it was half an hour in the garage and then we had to pack up and go."

"It's funny, because when Jacques Villeneuve won in 1997 at the last race in Jerez, that was one hell of a celebration - I left the party at 4:00 am and I don't drink! Yet when Nigel won, it was half an hour in the garage and then we had to pack up and go."

"Until eighteen months ago he really didn't get to know the people who work on his car very well at all. But in the last eighteen months he has made a real effort and got to know them. I think he was a bit rattled by Montoya at the end of last year and so he has become much more part of the team and got to know everyone by name. Montoya is a joker and larks around but Ralf is getting more like that."

"Until eighteen months ago he really didn't get to know the people who work on his car very well at all. But in the last eighteen months he has made a real effort and got to know them. I think he was a bit rattled by Montoya at the end of last year and so he has become much more part of the team and got to know everyone by name. Montoya is a joker and larks around but Ralf is getting more like that."

"At the same time, I'd like to see refuelling go. I have never been a fan of refuelling. With all the different strategies it must be difficult for Joe Public to understand what is going on. But if you had the tyre stops then you'd get fast four or five second pitstops and that would be quite exciting and easy to understand."

"At the same time, I'd like to see refuelling go. I have never been a fan of refuelling. With all the different strategies it must be difficult for Joe Public to understand what is going on. But if you had the tyre stops then you'd get fast four or five second pitstops and that would be quite exciting and easy to understand."

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 8, Issue 23

Atlas F1 Exclusive

Interview with Dickie Stanford

Jo Ramirez: a Racing Man

Articles

Blind Spot for Bernoldi

Canadian GP Preview

Canadian GP Preview

Local History: Canadian GP

Canada Stats and Facts

Technical Focus: Tyre Technology

Columns

The Canadian GP Quiz

Bookworm Critique

Elsewhere in Racing

The Grapevine

> Homepage |