|

|

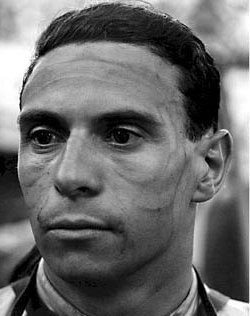

| Remember Jim Clark | |

| by Roger Horton, England | |

|

Sunday April 7th, 1968. It was an April day like any other April day. Dull, overcast with intermittent showers. In England the motor racing fraternity's attention was focused on the BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch. A six hour race for Sports cars. The grid was filled with Porches, GT40's, Lola-Chevrolets and Ferraris. Much interest surrounded the debut of Ford's successor to their GT40, the new Alan Mann Ford V-8 F3L.

The Deutschland Trophy was to be run in two heats. The track was still wet from heavy overnight rain, although it was only drizzling by the start of the first heat. Jim Clark had not gone well in practice and he lined up on the grid in 7th position. As he passed the pits to start his 5th lap, he was in 8th place and clearly in some trouble with his car. Jim Clark never completed that lap. As he drove round a slight right hand curve at over 140 MPH the car was seen to twitch, then to leave the circuit diagonally and to slam sideways into some trees. Jim Clark was killed instantly. A lot died with Jim Clark's death. It signalled the beginning of the end of the "amateur" era in F1. Although many more drivers would die for want of even elementary safety measures, both in terms of car construction and track design, so shaken were the drivers that under the leadership of Clark's great friend and rival Jackie Stewart, the push for change started. Run off areas, guard rails and gravel traps would greet the over-the-limit driver. Not trees, ditches and earth banks. Jim Clark, the son of a Scottish farmer, made his competition debut in June 1956 driving his own Sunbeam Mk 3 in a local sprint event. He won. Over the next 12 years he would dominate world motor racing like no one before or since. Two World Championships, twenty five Grand Prix victories, thirty three pole positions, winner of the 1965 Indianapolis 500, three times Tasman Champion. When you dig deeper and realize that two more World Championships slipped away in '62 and '64 through engine related failures at the final race, a clearer picture of his dominance emerges.

Indeed it was Dan Gurney that pushed Colin Chapman, the legendary founder of the Lotus company - for whom Clark drove almost exclusively throughout his career, to build a series of special cars to compete in the Indianapolis 500. In many ways it was Jim Clark's performances in oval track racing, a discipline in which he had no previous experience, that underlined just what a natural talent he possessed. In the early '60s Indy was dominated by front engined roadsters, powered by the Offenhauser engine that had been around since before the second world war! Clearly the Americans were unimpressed by the arrival of these Europeans with their rear engined cars so obviously intent upon winning their race and making off with the considerable prize fund on offer. Lotus could win more money in this one race than the entire Grand Prix season. For Colin Chapman it was both good business and a technical challenge.

His record at Indy was impressive. He won in '65, came second in '63 and '66. In '64 tire failure caused his retirement whilst leading. If his record was outstanding, his driving was sublime - he just made it look so easy. He could even spin and keep the car off the wall, not an easy thing to do now or then. Many watching racing in the sixties have a special Jim Clark memory. Brands Hatch in early 1965, the Race of Champions, one of the many pre-season F1 races run at that time. Clark was leading in his Lotus but being pressed hard by Dan Gurney in his Brabham. As they entered bottom bend Clark drifted too far out on the exit and his two outside wheels were on the grass. Unable to either regain the track or slow down, the car clipped a marshal's post and was destroyed. For an instant the sight of the broken Lotus was frozen in time until there was movement in the cockpit and Clark jumped out unhurt. The crowd, all too used to motor racing tragedies in the sixties, instinctively applauded to release the tension. The race soon ended and the Lotus team sent a truck to collect the remains of Clark's Lotus 33. The mechanics loaded the car and the person assisting them was none other than Jim Clark, O.B.E. World Champion racing driver, so soon to sweep all before him in the year ahead. No wonder a generation of mechanics at Lotus liked and admired him so much.

It is a familiar reaction. For some the memories are just too painful.

Perhaps also it is the realization that more than just a driver died at

Hockenheim all those years ago. Racing of that era extracted a terrible

price in terms of motor racing deaths, but racing was still a sport, not a

commercial endeavor. Jim Clark's 25th and last Grand Prix victory was the

last to be won by Lotus in their national colors. The commercial era had arrived.

Jim Clark was killed whilst at the peak of his powers. The victim of a mechanical failure that was beyond even his remarkable skill to overcome. In the end it wasn't his skill that deserted him, it was his luck.

|

| Roger Horton | © 1999 Atlas Formula One Journal. |

| Send comments to: horton@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |

At Hockenheim in Germany there was a minor Formula 2 race taking place, the

Deutschland Trophy. It was the second round of the European Formula 2

Championship. In those days Formula One drivers competed in races almost

every weekend. At Brands Hatch Denny Hulme and Bruce McLaren shared the new

Ford; in Germany the works Lotus cars were driven by Graham Hill and Jim

Clark.

At Hockenheim in Germany there was a minor Formula 2 race taking place, the

Deutschland Trophy. It was the second round of the European Formula 2

Championship. In those days Formula One drivers competed in races almost

every weekend. At Brands Hatch Denny Hulme and Bruce McLaren shared the new

Ford; in Germany the works Lotus cars were driven by Graham Hill and Jim

Clark.

Statistics alone, though, can never tell the full story, just as drivers

from different eras cannot and should not be compared. A driver can only be

judged against the other drivers he drove against. Clearly Clark totally

dominated his era and set the standards by which others were judged. Sure

he had challengers, Graham Hill and Dan Gurney throughout most of his F1

career, Jochen Rindt in F2 was a fierce competitor. Jackie Stewart was

emerging as his main rival in F1. Interestingly it was Jim Clark's father,

who at his son's funeral took Dan Gurney aside and told him that he (Gurney)

was the only driver Jim had ever feared on the race tracks of the world.

Statistics alone, though, can never tell the full story, just as drivers

from different eras cannot and should not be compared. A driver can only be

judged against the other drivers he drove against. Clearly Clark totally

dominated his era and set the standards by which others were judged. Sure

he had challengers, Graham Hill and Dan Gurney throughout most of his F1

career, Jochen Rindt in F2 was a fierce competitor. Jackie Stewart was

emerging as his main rival in F1. Interestingly it was Jim Clark's father,

who at his son's funeral took Dan Gurney aside and told him that he (Gurney)

was the only driver Jim had ever feared on the race tracks of the world.

For Jim Clark American racing was a dilemma. He hated the "over the top"

publicity and all the hype that surrounded the Indy 500, but as always it

came down to the fact that it was a race and he was a racing driver. It

challenged him and he was hooked.

For Jim Clark American racing was a dilemma. He hated the "over the top"

publicity and all the hype that surrounded the Indy 500, but as always it

came down to the fact that it was a race and he was a racing driver. It

challenged him and he was hooked.

Just how much, was demonstrated to me nearly thirty years after Clark's

death. It is another race paddock in another continent. During a lull in

activity I struck up a conversation with a team member whose accent

betrayed his English origins. He worked for Lotus in the sixties and so

inevitably the conversation turned to Jim Clark. For a few moments the

memories flowed before suddenly his eyes misted over and he turned away.

Just how much, was demonstrated to me nearly thirty years after Clark's

death. It is another race paddock in another continent. During a lull in

activity I struck up a conversation with a team member whose accent

betrayed his English origins. He worked for Lotus in the sixties and so

inevitably the conversation turned to Jim Clark. For a few moments the

memories flowed before suddenly his eyes misted over and he turned away.