All the Formula One cars built from 1950 until the end of 1969 had one thing in common: a central air intake in the nose of the car which supplied the engine with combustion and cooling air. This construction dictated the appearance of the traditional Formula One racing car. At that moment, An alternative didn't seem to exist.

It was the genius car-maker Colin Chapman who first entered new territory. He had already created the monocoque design in the early 1960s, which remains universal and indispensable to this day. But with his new Lotus 72 the engineer and team chief did away with the aerodynamically bothersome opening altogether. He made the nose a closed wedge, and the radiators disappeared into the boxes which formed the sides of the car.

Thanks to this pioneering invention, the Lotus 72 could travel 14 km/h faster on long straights than its predecessor the 49C, even with the same power engine. Other features of the racing car were torsion bar suspension and brakes located on the inside. The suspension was based on an idea of the legendary Professor Ferdinand Porsche from the 1930s. Moving the brakes inwards, which was not a Lotus invention either, reduced the unsuspended mass and hence improved road-holding.

The grandfather of all modern single-seaters had its debut in Madrid in 1970 for the Spanish Grand Prix. However, the construction suffered teething difficulties and was not capable of producing a win. Three weeks later, the World Championship race in Monaco was imminent and Lotus star Jochen Rindt returned willingly to the old 49C for this reason. By making this decision, Rindt, a German who had been living in Austria since he was three years old, laid the foundations for his victory that year of the World Championship.

The grandfather of all modern single-seaters had its debut in Madrid in 1970 for the Spanish Grand Prix. However, the construction suffered teething difficulties and was not capable of producing a win. Three weeks later, the World Championship race in Monaco was imminent and Lotus star Jochen Rindt returned willingly to the old 49C for this reason. By making this decision, Rindt, a German who had been living in Austria since he was three years old, laid the foundations for his victory that year of the World Championship.

At first the Monaco race was dominated by Jack Brabham, the champion in 1959, 1960 and 1966. The Australian was contesting the last season of his career and, despite being 44 years of age, he was still in stunning form. By half time the old master was in the lead and looked certain to clinch the race. Rindt, at the wheel of the Lotus museum-piece, was more than 15 seconds behind the man from Down Under. But at that point the Lotus driver began to excel himself. By the time they were ten laps short of the finish, Rindt had eaten away little by little at Brabham's lead, reducing it to 11.5 seconds. And then during the next nine laps he came a full ten seconds closer! Brabham still looked safe though.

With the Lotus filling his rear view mirrors, his plan was to out-think Rindt over the final lap. He chose the "battle line" in order to make it impossible for Rindt to out-brake him. But outside of the ideal line with its coating of rubber, the old campaigner lost control of his car and slid into the straw bales at the edge of the track. Jochen Rindt slipped inside and took the race. The race manager, who was too busy watching for Brabham to reappear, even forgot to flag the surprise winner!

It was at Zandvoort that Jochen Rindt first climbed into the futuristic Lotus 72. At last the potential of the construction had been brought to life. Rindt won the race and went on to collect maximum points in France, England and Germany. Ironically, it was back in his adopted home where his lucky run came to an end: Austria, which had been hosting a World Championship Grand Prix since 1964, saw an engine damage end Rindt's race prematurely.

No-one was to know that he would never start from the grid again. In the final practice for the Italian Grand Prix, his front right brake shaft broke as he approached the Parabolica. At the wheel of chassis number two, the car in which he had had so much luck during the summer, he crashed into the barriers and sustained fatal injuries. Despite this, by the end of the season no-one had managed to catch up with his lead in points, and so it was that Jochen Rindt became the first and only Formula One racing driver to be declared world champion posthumously.

No-one was to know that he would never start from the grid again. In the final practice for the Italian Grand Prix, his front right brake shaft broke as he approached the Parabolica. At the wheel of chassis number two, the car in which he had had so much luck during the summer, he crashed into the barriers and sustained fatal injuries. Despite this, by the end of the season no-one had managed to catch up with his lead in points, and so it was that Jochen Rindt became the first and only Formula One racing driver to be declared world champion posthumously.

Only a year later, Colin Chapman pulled yet another technical sensation from out of his hat. Unlike the type 72, the D version of which remained capable of victory until 1974, his new creation was a flop. In Zandvoort, Silverstone and Monza, Chapman entered his Lotus 56B - a development on the Indy car of 1968. Its unusual feature was that, instead of being powered by a conventional induction engine, it was driven by a double-shafted gas turbine manufactured by Pratt & Whitney, who originally designed it for use in ships, locomotives and helicopters. Jochen Rindt had supported the project, but neither Dave Walker, Reine Wisell or Emerson Fittipaldi - each of whom was given the dubious honour of driving the car - could make a success of the powerful monster.

With a fuel consumption of 100 litres for every 100 km, the almost silent power-pack proved exceptionally thirsty. The car had four-wheel drive and the sitting position was a long way forward due to the length of the turbine, and both of these factors were hard to get used to. But worse still, the power was delayed in kicking-in. This drawback demanded extraordinary skill from the drivers: they had to start pressing the gas pedal while still in the braking zone in order to achieve the required acceleration when leaving the curve. If they timed it wrong they either departed from the track or were left crawling out of the corner at a snail's pace.

Jochen Rindt's successor to the title was the Scottish Tyrrell driver Jackie Stewart, who had already won the World Championship in 1969. Then Lotus tasted victory once again. They were still relying on the type 72, which was now being driven with success by Emerson Fittipaldi. In 1973, the great Jackie Stewart had his third and final turn at the top. Already early on in the year he had confided in his boss Ken Tyrrell that he was going to retire at the end of the season, at which point he would be able to look back on exactly 100 Grand Prix races.

However, things transpired differently. Stewart's French friend and teammate Francois Cevert, who had been groomed by Tyrrell for victory, died in an accident during the practice session for the final race at Watkins Glen, and the Scot, mourning his friend, decided to forego the final contest. After his official retirement as an active driver - "As from today, I am no longer a racing driver" - he gave his wife a magnificent necklace: three diamonds symbolising his three World Championship titles, 27 brilliant cut diamonds for his Grand Prix victories, and 99 pearls for all the times he had started from the grid: one less than he had predicted.

However, things transpired differently. Stewart's French friend and teammate Francois Cevert, who had been groomed by Tyrrell for victory, died in an accident during the practice session for the final race at Watkins Glen, and the Scot, mourning his friend, decided to forego the final contest. After his official retirement as an active driver - "As from today, I am no longer a racing driver" - he gave his wife a magnificent necklace: three diamonds symbolising his three World Championship titles, 27 brilliant cut diamonds for his Grand Prix victories, and 99 pearls for all the times he had started from the grid: one less than he had predicted.

Shell also departed from Formula One racing along with Jackie Stewart. Since the very first Formula One World Championship, the oil multinational had been among the winners. At the end of 1971 Shell split from Lotus and BRM, and at the end of 1972 from Matra. One year later they then ended their partnership with Ferrari too. The first notorious Oil Crisis spelled the end of the oil company's involvement in Grand Prix racing.

During those years, Formula One technology stagnated. Most people's attention was on the engine department: here a twelve-cylinder from Ferrari, there the giant Ford V8. When Derek Gardner, that period's greatest Formula One car-builder, was asked how Formula One cars would develop, he put his finger on the weak-spots without hesitation. Steps forward, he said simply, would be made in aerodynamics in the future. He turned out to be right, but the time had not yet come for quantum leaps in this field.

For a while, however, a totally new concept looked as though it might revolutionise Formula One. Tyrrell presented the now legendary P34 in 1976. Its most noticeable feature was that it had six wheels - two conventional rear drive wheels and four at the front. But the success they were seeking did not appear, even though the 'Centipede' did manage to secure a double victory.

For a while, however, a totally new concept looked as though it might revolutionise Formula One. Tyrrell presented the now legendary P34 in 1976. Its most noticeable feature was that it had six wheels - two conventional rear drive wheels and four at the front. But the success they were seeking did not appear, even though the 'Centipede' did manage to secure a double victory.

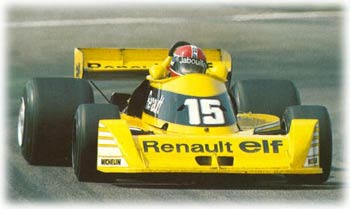

New territory was charted in 1977. In July of that year, Renault brought the first car with a turbocharged engine onto the starting grid. Formula One had last seen forced-aspiration units in 1951. The yellow Renault, piloted by Jean-Pierre Jabouille, began by trailing behind hopelessly. The little 1.5 litre engine started out weak, unreliable and difficult to drive; the V6 engine's turbo made life difficult for Jabouille. Nevertheless, the French found themselves on the road to success after a while.

Around the same time, Lotus boss Colin Chapman 're-discovered' aerodynamics. His Lotus 78 was a ground-breaking design straight out of the wind tunnel. Strips along the sides of the car reached right down to the asphalt. On account of this legal trick, the driving wind flowing beneath the type 78 was accelerated to such an extent that suction was created, holding the car to the floor and thus enabling it to corner at a phenomenal speed.

The concept took no more than a year to mature, and Lotus driver Mario Andretti scooped the Championship title with ease. The only theoretical threat to the American was his team colleague Ronnie Peterson, but the latter was subject to the rules of a clear team hierarchy which forbade him to launch an attack on Andretti. At Zandvoort, the Swede once again shadowed the every move of Lotus's Number One driver and the internal rules of the game became clear for all to see. Coming out of the famous Tarzan Corner, Andretti mis-changed while accelerating, and the obedient Number Two only managed to avert an almost unavoidable overtaking manoeuvre by stepping hard on the brakes...

Brabham tried to defy the aproned Lotus by 'above-board' means. At the start of the season, the South African designer Gordon Murray had brought out the BT46, which, for aerodynamic reasons, had no radiator opening whatsoever! Heat exchanger tiles were stuck to the outside of the racing car in order to keep the oil and water temperature within moderate limits. However, the system only functioned in theory and the BT46's engine was already boiling over during test runs prior to the first World Championship race. Much to the distress of the aerodynamics engineers, holes promptly had to be cut into the cladding...

Brabham tried to defy the aproned Lotus by 'above-board' means. At the start of the season, the South African designer Gordon Murray had brought out the BT46, which, for aerodynamic reasons, had no radiator opening whatsoever! Heat exchanger tiles were stuck to the outside of the racing car in order to keep the oil and water temperature within moderate limits. However, the system only functioned in theory and the BT46's engine was already boiling over during test runs prior to the first World Championship race. Much to the distress of the aerodynamics engineers, holes promptly had to be cut into the cladding...