|

|

| Baywatch | |

| by Nick Lewis, England; Photography: LAT | |

|

What exactly goes on in the feared arena of the scrutineering bay? Ron Dennis flashes a wolfish grin. "In Formula One, the scrutineers are the equivalent of Customs and Excise," he says. "During any race weekend they can come on to your premises at any time, and as often as they want."

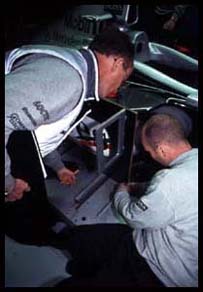

The scene is the pitlane at Canada's Circuit Gilles Villeneuve on the Thursday prior to the Canadian Grand Prix of 1998. A posse of FIA officials arrives at the McLaren garage where the trio of gleaming silver MP4-13s sits silently poised for action over the coming days. Before these cars can be allowed out on the circuit for even a single lap, they are obliged to be scrutineered in detail by officials from the sport's governing body to ensure they comply with the exhaustive safety regulations. It's part of an ongoing process throughout every Grand Prix weekend to check that every competing car strictly conforms with the regulations every second that it is on the track during practice, qualifying and the race proper. Scrutineering has come a long way over the years. Thirty years back, mechanics could get away with sitting on a rear wing in order to bend it back down to regulation height. There were ruses such as refilling oil catch tanks to the brim in order to bring the car back up to the requisite minimum weight limit. Not so these days. The modern scrutineers, headed by Charlie Whiting, head of the FIA's Technical Department, and Technical Delegate Jo Bauer, start by verifying every single item that could have an influence on the car's safety and security. Though the FIA has already given the green light to individual car designs by the imposition of pre-season crash tests, scrutineers still check that the MP4-13 nose sections have not been modified and that their rear impact structures remain the same as they were when originally tested (if they're modified, they must be resubmitted to the FIA). The scrutineers then examine the fuel filler, seat belts and even the fire extinguishers before checking that the car rear light and safety equipment is in order. Even at this stage, there is reason to ensure the cars meet rules on dimensional conformity. Practice may still be informal, but the FIA rules clearly state that cars must conform to all the technical regulations at all times. McLaren and rival teams take their cars to the scrutineering bay throughout the GP weekend to check the cars themselves with the same equipment that will be used in the official pre-race test. "The scrutineering bay is open from 7.30 in the morning until 7.30pm on all the days of a GP," says Steve Hallam, Head of Race Engineering. "In that time anyone can satisfy themselves at any time that their car conforms to the rules simply by pushing it down there and using the FIA equipment. When 7.30 in the evening arrives, they place a marker cone behind the last car in the queue so everybody knows not to bring any more cars up to the bay until the following morning.

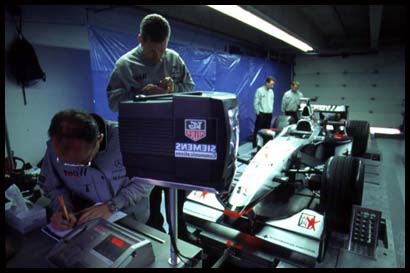

"Ron is quite correct to compare it to HM Customs and Excise. Right down to the onus being upon us as team entrants to prove our cars' conformity to the regulations rather than the other way around." On Friday the trio of MP4-13s is pushed up the pitlane to the official scrutineering bay to be checked over prior to official qualifying. The cars are pushed up on to a sophisticated weighing platform to ensure that they conform with the 600kg minimum weight limit, and at the same time a flat surface is raised beneath them to make a 'reference plane' from which all the car's dimensional measurements can be taken and precisely verified. As far as engines are concerned, the FIA couldn't possibly check every engine for every race and only rarely does it check bore/stroke dimensions to ensure they meet the current 3-litre capacity limit. In the past, FIA staff have examined bores with special instruments that could be inserted through the car's spark plug aperture. Instead, perhaps three or four times a season, scrutineers will randomly choose an engine to be sealed at the circuit and stripped down for detailed examination at the engine manufacturer's premises in the presence of the FIA technical staff. Like all its rivals, the West McLaren Mercedes team would be ready to comply immediately with any such request by the FIA should one ever be made. Of course, once practice and qualifying get underway at Montreal, both Mika and David are always aware that they may attract random checks by the scrutineers at any time. These can include fuel sampling, in which specimens of the MP4-13's Mobil fuel can be taken and put through gas chromatographic analysis, the results of which are compared to a 'fingerprint' of a sample held by the FIA. The scrutineers take a similarly rigid attitude towards checking the software systems that are part and parcel of every contemporary Grand Prix car. Responding to fears that it lacked the technology required to examine these systems fully in years past, the FIA has now evolved a comprehensive package to police this highly sensitive domain. It's done by pre-approving - versions of software submitted by each team in advance. This is checked at source code level to ensure that it cannot carry out any function that the scrutineers feel it should not - illegal traction control, for example - and a copy is duly taken. At any time during a race weekend thereafter, FIA personnel can descend on any car in the pitlane and request that the software is uploaded on to their own computer to be checked byte for byte against a reference copy lodged earlier. This takes only a few minutes, but it can still cause a crucial interruption to the team's technical set-up programme. "Only this Friday we had one of the FIA's scrutineers in our garage asking to upload the details of our software for one of their routine checks," says Steve Hallam. "Our first reaction, quite naturally I suppose, was 'Oh no, not now in the middle of a practice session'. To be fair, he did agree to wait until the cars had stopped running, although he insisted on remaining in the garage until then. Of course, this is quite within the scrutineers' rights and it's inevitable that when your car is competitive you expect it to be checked over pretty frequently - and believe me, it always is."

The final outcome of this, of course, is that sometimes a car and driver may go three races without being checked. Yet, by the same token, it's equally possible for one car to be checked three times in a single session. No wonder that the drivers approach the pitlane entrance with more than a degree of trepidation. No explanation of scrutineering would ever be complete, from the McLaren point of view, without reference to the 1992 Canadian Grand Prix, won by Gerhard Berger's MP4/7. At the preliminary post-race inspection, scrutineers found that the car's rear wing dimensions were right on the outer margins of acceptability for the regulations in force at the time. In those days the FIA scrutineers had no precise means of measurement with which to check a car's dimensions, so Berger's MP4/7 was examined at three different places in the pitlane before it was taken to one of the garages for a detailed, inch-by-inch inspection. Only after this was it finally pronounced legal. The episode was a perfect example of what Formula One engineering is all about: taking a set of rigorously specific regulations and then exploiting them up to the hilt. Maximising the car's performance potential without attracting the attention of those ever-vigilant individuals, the FIA scrutineers. Certainly, you don't want to break rules; but you want to come close.

The ones they caught out

|

| Nick Lewis | © 1999 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: comments@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |

| The article was prepared by and appears courtesy of TAG-McLaren Communications Office |

He's absolutely right, although there is one critical difference between

the scrutineers and Customs: the West McLaren Mercedes team and its

rivals actually expect the FIA enforcers to put in an appearance. No

ifs' only whens.

He's absolutely right, although there is one critical difference between

the scrutineers and Customs: the West McLaren Mercedes team and its

rivals actually expect the FIA enforcers to put in an appearance. No

ifs' only whens.

Another possible interruption comes in the form of a random pitlane

weight check. The FIA computer has a 'random generator' in its programme

that selects about one in four cars arriving in the pitlane. The

computer may say "weigh the third car to come in", which takes the

entire process beyond suspicion because no team knows which is going to

be the third car to enter the pitlane at any moment during a practice or

qualifying session.

Another possible interruption comes in the form of a random pitlane

weight check. The FIA computer has a 'random generator' in its programme

that selects about one in four cars arriving in the pitlane. The

computer may say "weigh the third car to come in", which takes the

entire process beyond suspicion because no team knows which is going to

be the third car to enter the pitlane at any moment during a practice or

qualifying session.