|

This time, the second part of a look at the 1959 Season and Our Scribe ponders a few other items as well.

1959: Part 2, Monte Carlo to Aintree

The debut of the new Cooper 51 at the International Trophy at Silverstone was a revelation. Unlike previous Cooper designs - the 41, 43, and 45, whose handling characteristics could be summed up in one word: Understeer - the 51 was a very nice handling car. One reason was, that it could be made to understeer which greatly expanded its capabilities and made life easier for the drivers. It was also smaller and more aerodynamic than the other cars being campaigned that season. With a Climax FPF engine and the new gearbox that it built over the winter, suddenly Cooper looked like a contender.

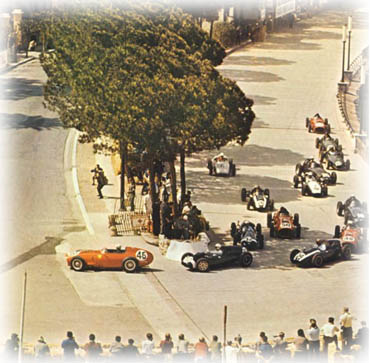

The tenth season of the World Championship finally got underway with the Grand Prix of Monaco. The race through the streets of Monte Carlo was 100 laps - almost three hours of gear changes, corners, and, well, things to hit. The tenth season of the World Championship finally got underway with the Grand Prix of Monaco. The race through the streets of Monte Carlo was 100 laps - almost three hours of gear changes, corners, and, well, things to hit.

There were 24 entries vying for 16 places on the starting grid, so practice was a complete shambles. Of the entries, seven were Formula Two cars. Of these, the 718/2 entered by the Porsche factory for Wolfgang von Trips and the Dino 156 entered by Ferrari for Cliff Allison attracted the most attention.

When the dust settled and the time ran out, it was the Usual Suspects on the grid for the most part. The front row had Stirling Moss on the pole in his Rob Walker-entered Cooper 51-Climax, with Jean Behra's Ferrari Dino 246 (or 256 since the V-6 had been enlarged from its original 246 cc displacement to a full 2.5 litres) and Jack Brabham in a works Cooper 51-Climax filling

out the front row. It is interesting to note that the second row of the grid was filled with the snub-nosed Ferraris of Tony Brooks and Phil Hill, both doing an excellent job of hustling their cars around the track.

As was the norm in those days, the period prior to the start was chaos. The drivers had a series of meetings and grip-and-grins with the famous and the notorious on the slope of the Palace Rock. There had been no end of confusion over badges and armbands all weekend. Somewhere along the way, Brabham had misplaced his armband. As Brabham crossed the Boulevard to enter the pits, one of Monaco's Finest pointed out that since he lacked the necessary armband, sorry, but no entry.

Without much patience for such nonsense in the best of times, much less before a race, Brabham had no inclination to watch the race from the Royal Box. He backed off, and then plunged through the police line! As he ran into the Cooper pits, pursued by a large number of unhappy members of Monaco's Finest, the mechanics formed a protective huddle around Brabham. Someone managed to find an armband and shove it into Brabham's hand. The irate leader of the band of uniformed officials, clubs at the ready to thump the offender senseless, demanded Brabham be offered up for justice. Brabham produced the armband and inquired if there was anything else he could help them with. The police retreated, albeit with great reluctance.

At the start, it was Behra making a rocket start into the Gasometre corner ahead of most and Brabham. The start/finish line was about where the exit from the swimming pool corner is today. It was essentially a drag race for several hundred meters and then a hairpin, the exit taking the cars past the current start/finish area and pits to St. Devote and so forth. Behra had the bit between his teeth and was motoring off into the distance, the pack nipping at his heels.

The same could not be said about the Formula Two race. Three of the Formula Two cars had qualified - von Trips, Allison, and Bruce Halford in a Lotus 16-Climax, entered by John Fisher. As he was exiting St. Devote heading up the hill to the Casino, von Trips hit some oil and spun. Allison initially seemed to be headed for the gap between von Trips and the wall, but ended up

hitting both. And then Halford managed to pile into them both. End of the Formula Two race on the second lap.

After 20 laps, Behra was in the lead, but as he exited the Casino down to the Station Hairpin and the tunnel, his engine started to tighten up. At the Chicane, Stirling Moss nipped by to take the lead. Behra pulled into the pits and soon afterwards retired. Brabham and Brooks were now trailing Moss. Unfortunately for Brabham, a design flaw of the Cooper 51 was beginning to cause him some serious problems. The heat from the radiator was heating up the pedals making them difficult to use. Although generous qualities of cardboard was applied to the area around the pedals, it was still too hot for comfort. Brooks and other Ferrari drivers were having to deal with the high sides of their cockpits which were turning to heat traps.

By the mid-point of the race, half the field had retired. Only Brabham and Brooks were on the same lap as Moss. It seemed to be heading for another Moss victory, until Moss pulled into the pits with less than 20 laps to go. He complained of a noise coming from the rear of the car. A quick inspection by Alf Francis, the head mechanic for the Rob Walker team, revealed nothing obvious and so Moss returned to the fray. As he accelerated out of Gasometre, he felt the gearbox give up and coasted to a stop on the road above the pits.

In the meantime, Brabham had swept by into the lead, followed by Brooks, and third was now Roy Salvadori in the Cooper 45-Climax entered by High Efficiency Motors, two laps arrears. That is, Salvadori was third until his gearbox took a hint from Moss' and packed up several laps later, barely a dozen laps left in the race. Although Brooks managed to close within ten seconds at the finish, Brabham held on for the win. Following Brabham and Brooks across the line was the other Rob Walker Cooper driven by the 1955 and 1958 winner of the race, Maurice Trintignant.

In the results, Jack Brabham is given credit for setting the fastest lap of the race on lap 83, 1:40.4, 112.771 kmph. There were those who somehow missed the lap time on their charts, and given the nature of how oily the track was at that point; Brabham's condition (his feet were in poor shape by the end of the race); and that it was Brooks gaining on Brabham - doubts were raised, but Brabham still got the point.

Although it was the third victory for Cooper, it was the first for the works team. With Monte Carlo considered a "Cooper Circuit," not much was made of the victory. The Learned Scribes of the days still tipped Ferrari as a sure

bet to take the Championship, especially now that Vanwall was gone. After Monaco, it was said, Ferrari would take charge and either Brooks or Behra would emerge as the Champion. Cooper, Brabham, and Climax were all just lucky. Wait until the "real" circuits came up.

The next two Championship events were a day apart: the Indianapolis 500 and the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. At Indianapolis, Rodger Ward guided his Leader Card Watson-Offy to victory by 23 seconds over Jim Rathmann. A new safety feature mandated for 1959 by the United States Auto Club (USAC) was a roll bar for the roadsters. The spate of accidents during 1958 led USAC to

add this to seatbelts and helmets as mandatory safety items. After a fire during practice, which claimed the life of Jerry Unser two weeks later, USAC also added the requirement for flame-retardant overalls. This latter requirement was effective immediately.

On the day following Indianapolis, the Grand Prix Circus raced at Zandvoort. Scuderia Ferrari was expected to dominate and soundly trounce the opposition. Only they forgot to tell the opposition. On the pole was the BRM P25 of Joakim Bonnier. A BRM on the pole was highly unusual and nothing short of amazing considering the miserable record the team had built up over the years.

Next was Jack Brabham's works Cooper 51 and filling out the front row was Stirling Moss in the Rob Walker Cooper 51. The first Ferrari Dino was Jean Behra on the inside of the second row, with Graham Hill putting Team Lotus on the outside of the row in a Lotus 16. The other Ferrari Dinos of Tony Brooks and Phil Hill were buried in the field. Buried along with them were the Aston Martins of Carroll Shelby and Roy Salvadori, making their World Championship debut.

Prior to the beginning of the season, both of the 1958 Cooper works drivers, Salvadori and Brabham, had indicated that they intended to accept drives with the Aston team. After all, it was a highly successful sports car team and they paid better than the Coopers. Brabham began to have cold feet as he watched the Climax FPF come to life. And the type 51 offered an excellent

platform for the new engine, and the new gearbox being made in-house would solve the transmission problems of previous seasons.

Whereas Brabham backed (messily) out of the Aston ride, Salvadori felt that he needed to honor his commitment and stayed with the team. With Salvadori going to Aston, John Cooper needed a third driver for the team. To Brabham and Masten Gregory, he added a New Zealander working in his shop who had "some talent," by the name of Bruce McLaren.

After seasons of trouble, turmoil, disaster and empty promises, the pole position was considered a major triumph for the Owen Racing Organisation. The team was determined to do well. Bonnier led from the start but was soon passed by Masten Gregory after the first lap. Bonnier passed Gregory after ten laps and assumed the lead. Then Brabham caught up with first Gregory and then Bonnier and went into the lead for four laps before Bonnier took back the lead. After being held up by Behra's extra wide Ferrari in the early going, Stirling Moss swept by Brabham and Bonnier for the lead.

The new Cooper gearbox was giving Brabham problems. He lost second gear and with the corners behind the pits needing second gear, he was slowly dropping back. Bonnier was wondering when the usual gremlins would strike and ruin the excellent run by the BRM. There had been brake problems earlier in the season that were serious enough to lead to discussions that unless they were resolved, the team would not come to Zandvoort. An unusual aspect of the BRM design was that there was only a single rear disc brake, which worked off the end of the rear-mounted transmission. Unorthodox and clever, it was also a point of concern, having not been very good at its job over time.

Then Bonnier flashed by the pits in the lead. Only a dozen laps from the end of the race, the transmission in the Moss Cooper failed. Bonnier sailed around for the final dozen laps, and gave BRM its maiden victory. Brabham kept his second place and was joined by his teammate Masten Gregory in third. The first Ferrari home was Jean Behra in fifth, one lap down. To add injury to the insult, Innes Ireland brought his Lotus 16 home in fourth place. The Scuderia was not happy with the results. Behra was furious with the clear lack of performance of the Dino. The point for fastest lap was initially split between Bonnier, Gregory, and Moss at 1:37.2, but later was corrected to one time of 1:36.6, 156.090 kmph, set by Moss on lap 42.

It was a popular win for the team from Bourne. After years as being the butt of no end of jokes, victory was sweet. The team had managed to find no end of new ways to lose races. The win was a much needed boost to a team in true need of a ray of sunshine. However, the team still managed to find a way to spread some gloom on things. The evening prior to the race, it was announced

that the Owen Racing Organisation was loaning two of its BRM P25s to the British Racing Partnership, a team run by Alfred Moss, the father of Stirling Moss, and Ken Gregory, Stirling's business manager. This did not go well within the BRM team. It was necessary after the win for Alfred Owen to remind certain members of the team that it was the OWEN Racing Organisation.

With the cancellation of the Belgian Grand Prix due to financial difficulties, the Usual Suspects next showed up at Rheims. The 8.3 km circuit was one of the fastest in Europe, being in competition with Spa-Francorchamps and Monza for that title. Essentially a series of connected straights on the edge of town with only one slow corner, the hairpin at Thillois, the corner leading to main straight. The Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France also carried the additional title of the European Grand Prix this year. The race meeting was held in unbelievable heat. The temperatures hovered at the 40°C mark the entire time and climbed to 43°C one day. It was sweltering. The Cooper team worked overtime to find some way to get some cooling for the feet of its drivers.

The Scuderia finally was in its element. Ferrari drivers filled three of the top five spots on the grid. Tony Brooks took the pole and the 100 bottles of champagne that went with it. Phil Hill was on the outside of the front row with Jean Behra on the outside of the second row. In the middle of the front row was Jack Brabham and on the inside of the second row was Stirling Moss

in the BRP BRM. The other two entries from the Scuderia for Dan Gurney and Olivier Gendebien were on the fifth row of the grid. The first six rows of the grid all broke the previous year's pole position time.

It was the usual shambles on the grid. When he dropped the flag, Toto Roche barely had time to scamper off the grid and into the pits. Tony Brooks and Joakim Bonnier both only narrowly avoided collecting Toto. Tony Brooks then motored off into the distance and was never really challenged until the flag dropped at the end.

However, the race was anything but a dull procession behind Brooks. Until mid-distance, there were a series of fights for second place involving Stirling Moss, Masten Gregory (works Cooper), Maurice Trintignant (Rob Walker Cooper-Climax), Jack Brabham and Phil Hill. At the mid-way point, Phil Hill muscled by Brabham and put a lock on second place.

The conditions were horrid. The cockpits were sauna-like torture chambers. The heat caused certain parts of the circuit to start breaking up - the Thillois hairpin in particular being very bad. All around the circuit stones were being tossed up the tires at drivers, spectators and the radiators. Holed radiators put Graham Hill and Dan Gurney out of the race. Masten Gregory was pulled from his Cooper on the verge of heat stroke. His Cooper sat in the pits for the rest of the race, only needing a driver. BRM team

driver Ron Flockhart had his goggles hit by a stone with a sliver of glass lodging in his eye. He drove most of the race like that, finishing second. Even Moss got caught out by the conditions: as he braked for Thillois, the previous driver through the corner had gone wide and scattered stones on to the racing line. Moss spun off, stalled, and was unable to restart the BRM.

Brooks, Phil Hill and Brabham all made it to the finish, but were nearing exhaustion. Brabham could barely stand since the heat had blistered his feet. Although the front-engined Ferrari Dino had emerged victorious, the fact that Brabham was in third wrote volumes about the future.

The next stop was Aintree and the British Grand Prix. The circuit and its environs had all the charm of a toxic waste dump. The contrast between the vineyard country surrounding Rheims - even when scorching hot - and Aintree were Noted By All, as several Continental Scribes crouched it in polite terms.

All the Usual Suspects showed up except for Scuderia Ferrari, who cited a metal-workers strike as the cause of their non-appearance. Strangely enough, Scuderia Centro Sud appeared apparently unaffected by the strike. Vanwall was back for a one-off, with Tony Brooks at the wheel. Aston Martin had skipped Rheims and was now back. To provide even more entertainment for the spectators and competitors alike, the organizers opened the 24 positions on the grid to Formula Two cars.

After the usual shambles came to a halt, the front row had Brabham on the pole, Roy Salvadori and an Aston Martin in the middle and the BRM of Harry Schell in the outside position. Moss could only place his BRP-entered BRM in middle of the third row. Both Masten Gregory (works Cooper) and Maurice Trintignant (Rob Walker Cooper) qualified ahead of Moss. Once again, the RAC timekeepers used hourglasses to clock practice, times being to 1/5 of a second.

When the flag dropped, Brabham shot off into the lead and the race was for second. Moss was in that position virtually the entire race with Bruce McLaren (works Cooper) emerging as the only one able to close in on him in the last dozen or so laps. A last minute stop for fuel allowed McLaren into second for a lap. Moss passed him and managed to keep him at bay, but McLaren's performance received considerable attention by the Scribes present. Moss and McLaren shared the fastest lap with a time of 1:57.0.

After Aintree, Brabham led Brooks 27 points to 14 points. This was not what the Scuderia has in mind at all. And the problems had already begun back at Maranello. After retiring from the race at Rheims with engine failure, Jean Behra and team manager Tavoni had a shouting match in the pits that spilled over into harsh words back at the factory. As a result, Behra was released

from this contract. An attempt by BRM to sign him after the race at Aintree got tangled up in some details and it was expected that by Portugal he would be part of the BRM team once more.

Next time: part 3 of the 1959 saga, from the AVUS to Sebring.

Scribbles from the Scribe

As mentioned earlier, I will be taking a look at the 1982 season in

the very near future. As I look at this season, I am amazed that so much

seemed to be happening both on and off the track. With luck, it will prove

worth reading.

Another story that needs to be told is the real story of the 1933

Tripoli race. It is one of those stories where the truth certainly isn't

pure and simple. The credit for this idea goes to Betty Sheldon whose

research into this fascinating chapter of racing history deserves broader

recognition.

Keep the cards and letters - okay, emails - coming folks. Ideas and

questions welcomed.

|

Rear View Mirror

Rear View Mirror

Rear View Mirror

Rear View Mirror