|

|

| The Best of the Best | |

| by Barry Kalb, Hong Kong | |

|

Atlas F1 is proud to present a series of features on the all-time greatest drivers of Formula One, written by veteran journalist Barry Kalb.

This week's feature: Clark and Stewart In almost any racing season, there are one or two drivers who possess that extra amount of drive, that extra bit of racing sense, and above all - that extra bit of innate physical ability, that put them a cut above the rest. Year in, year out, these men will give their all virtually any time they step into a racing car; they will dominate a season when they are in a good car, and produce wins nobody thought possible in a mediocre car; they will turn in performances that racing aficionados talk about for decades to come. This is their story.

Clark was just as good against fellow drivers as against the clock. He was the first driver to break Fangio's record of 24 grand epreuve wins, chalking up 25 before his racing death in 1968. He was world champion twice, in 1963 and 1965, and would have won in 1962 had a small bolt in his engine not undone itself in the last race of the season, while he was in the lead. He changed the face of Indianapolis forever: he and his rear-engined Lotus-Ford almost won the legendary 500-mile race on the first try in 1963, did win in 1965, and in the bargain passed the death sentence to the old front-engined, Offenhauser-powered Indy racers.

A young Jackie Stewart was once watching Clark practice, going faster and faster, and as Clark sailed effortlessly around a corner and sped off down the straight, Stewart exclaimed: "He doesn't even use all the road!" Like a number of drivers, Clark likened racing at the highest level to an art form. "The supreme attraction of motor racing to me is driving a car as near the physical limit as possible without stepping over it," he wrote in his 1964 autobiography, Jim Clark At The Wheel. "It is like a born artist being able to place paint on canvas and make it a picture, whereas the majority of us would only make a mess. For I consider motor racing is an art." He continued, in a chillingly prophetic remark: "I have often said, and other drivers have also said this, that a racing driver only fears a mechanical failure in his car." He was killed in a Formula 2 Lotus during a non-championship race at Hockenheim in 1968, when the front end collapsed. Enzo Ferrari said of him: "Clark was without doubt one of the greats, one of those whom one counts on the tips of the fingers."

Stewart is remembered not only for driving ability, but for spearheading a movement to make racing safer. After a serious crash at Spa in 1966, he was appalled at the lack of safety features and emergency preparations at the world's leading tracks, and he began lobbying tirelessly to make safety a priority. "If I have any legacy to leave the sport, I hope it will be seen to be in an area of safety," he once said, "because when I arrived in grand prix racing so-called precautions and safety measures were diabolical."

There was a curious gap of 11 years, between Stewart's retirement in 1973 and Ayrton Senna's debut in 1984, during which, for the first time in motor racing history, there was arguably no driver of the very top rank who was active on the Formula One circuit. Ronnie Peterson, the Swede who drove during this period, was certainly very, good, and scored 10 grand prix wins, but he was never a serious contender for the top level of drivers. Another bright star who flashed briefly across the scene during these years was Gilles Villeneuve, father of the 1997 world champion, Jacques. There were those who ranked the elder Villeneuve among the greats, including Enzo Ferrari, who told this reporter and others that the Canadian was the only driver in a long time to remind him of Nuvolari. But there were also those who called Villeneuve simply a wild man. Villeneuve was killed in Austria in 1982, having completed only three full seasons, and his death did not surprise many people. He scored six wins in that short career, but it was too short a time to allow a lasting judgement. Alain Prost began his spectacular grand prix career in 1980, yet despite the fact that ended as the all-time leader in championship wins, podium finishes, fastest laps and points scored, despite his undeniable ability, Prost lacked the special spark behind the wheel that separates the great from the merely excellent. He has to be placed with several other drivers in the not-quite category.

|

| Barry Kalb | © 1999 Atlas Formula One Journal. |

| Send comments to: bkalb@asiaonline.net | Terms & Conditions |

Barry Kalb is a veteran journalist of 20 years' experience (the Washington Star, CBS News, Time Magazine) and a motor racing fan - especially Formula One - for almost 40 years. He currently resides in Hong Kong. | |

No driver ever displayed sheer, fluid driving talent, the ability to take a given car around a given track in the fastest possible time with less apparent fuss, better than Jimmy Clark. The slender Scotsman's record on pole positions, where a driver shows who can wring the last hundredth of a second out of his car, is testimony to his skill: Clark ran up 33 poles in 72 races, statistically second only to Fangio, and more in absolute numbers than anyone in his time. Only Ayrton Senna has since surpassed him (65 poles), but it took Senna 161 races to do so.

No driver ever displayed sheer, fluid driving talent, the ability to take a given car around a given track in the fastest possible time with less apparent fuss, better than Jimmy Clark. The slender Scotsman's record on pole positions, where a driver shows who can wring the last hundredth of a second out of his car, is testimony to his skill: Clark ran up 33 poles in 72 races, statistically second only to Fangio, and more in absolute numbers than anyone in his time. Only Ayrton Senna has since surpassed him (65 poles), but it took Senna 161 races to do so.

Clark's dominance of the 1963 season was phenomenal: out of 10 races, he qualified first seven times, second once. He won seven times, came second in one race, third in another, and retired in the remaining race while in the lead. He set fastest lap six times. At the U.S. Grand Prix that year, he was on the front row of the grid when his battery failed on the starting line; he lost a lap in the pits, and then worked his way steadily through the field to end up third, setting fastest lap in the process.

Clark's dominance of the 1963 season was phenomenal: out of 10 races, he qualified first seven times, second once. He won seven times, came second in one race, third in another, and retired in the remaining race while in the lead. He set fastest lap six times. At the U.S. Grand Prix that year, he was on the front row of the grid when his battery failed on the starting line; he lost a lap in the pits, and then worked his way steadily through the field to end up third, setting fastest lap in the process.

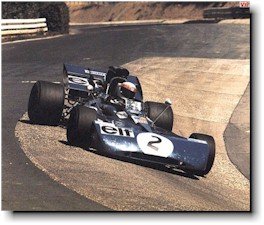

The next great driver to come along was Clark's fellow Scotsman, Jackie Stewart. Stewart started Grand Prix racing in 1965, as Number Two to Graham Hill at BRM, and scored his first championship win that same year in Italy. He later moved on to Matra and then Tyrell, and largely dominated Formula One over the six seasons after Clark's death, 1968-1973. He was a methodical, unspectacular driver, but like Clark, he ran up a stupendous record: out of 99 starts, 27 wins (a record that stood for 20 years; Stewart still ranks fifth in total championship wins). During those six seasons he was champion three times, in 1969, '71 and '73, and second in 1968 and 1972.

The next great driver to come along was Clark's fellow Scotsman, Jackie Stewart. Stewart started Grand Prix racing in 1965, as Number Two to Graham Hill at BRM, and scored his first championship win that same year in Italy. He later moved on to Matra and then Tyrell, and largely dominated Formula One over the six seasons after Clark's death, 1968-1973. He was a methodical, unspectacular driver, but like Clark, he ran up a stupendous record: out of 99 starts, 27 wins (a record that stood for 20 years; Stewart still ranks fifth in total championship wins). During those six seasons he was champion three times, in 1969, '71 and '73, and second in 1968 and 1972.

He has continued contributing to racing since his retirement, for several years as a television commentator, and, since 1997, as the head of his own grand prix team. But he will be remembered first and foremost for his driving ability. Enzo Ferrari said of Stewart: "He is entered with authority on the list of the greatest of all time."

He has continued contributing to racing since his retirement, for several years as a television commentator, and, since 1997, as the head of his own grand prix team. But he will be remembered first and foremost for his driving ability. Enzo Ferrari said of Stewart: "He is entered with authority on the list of the greatest of all time."