|

Saving the Best 'till Last |

| by Doug Nye, England; Photography: LAT | |

|

Strange though it might seem in the current climate of a jam-packed motor racing calendar, F1's closed season is more secure and longer lasting today than it once was. Take for example 1974, when January saw the new World Championship series open with the Argentinean Grand Prix, run on the Parque Almirante Brown Autodrome circuit in Buenos Aires. It was an important race for Team McLaren in several ways. Most significantly, it was its first race under the colours of a new sponsor, and it was also the first race with the former World Champions Emerson Fittipaldi and veteran Denny Hulme teamed together. Their racing cars were the year-old M23 chassis and in preparation for that early start to the 1974 Championship, new boy Emerson, fresh from Team Lotus, had been testing flat out through the autumn and winter at Ricard-Castellet in France. For the new year's racing, the already successful M23 design had been modified with a 3in longer wheelbase and a 2in wider rear track. In Argentina the GP was slated to be run on the longer new No.15 Autodrome circuit. Denny believed that Team McLaren might have been in with a better chance on the old, shorter one. "The longer course makes it a bit easier for the driver, because there's not much to do as you thunder down those long straights, but I figure the car has to work a bit harder..." In qualifying, he just managed to scrape into the top 10 bracket. "But I wasn't too worried about that." He tried out his M23 on full fuel tanks in the warm-up on race morning. "It was pleasant to find that only Carlos Reutemann of Brabham and Mike Hailwood in his Yardley McLaren M23 were any quicker."

In those days Latin American races seemed always to start with a multiple accident. "Mike Hailwood made a good start from alongside me," recalled Denny, "and we set off together. Then I was semi blocked off for a fraction, and I had to make up my mind whether I should try to go round Clay Regazzoni's Ferrari. The Ferrari was difficult to get off the line because of all the extra fuel it carried, and I didn't want to swerve past, because it might have squashed someone next to me. "Then I found I was sandwiched between Mike and Clay. Right away I backed off and at that moment Mike and Clay clashed in a sheet of magnesium sparks. Mike scrambled through, Clay swung to his left and I came through from behind to find Peter Revson's Shadow sideways in front of me. "He was heading for the infield, where I had decided to go. It now seemed inevitable that I'd run over his nose, but when there was no thump or thud, I knew I was clear..." Studying his mirrors, Denny saw nobody in his wake and assumed that there had been an almighty pile-up and that the race would be red-flagged. But it was not: the colliding cars had all spun clear onto the grass verge. "The accident had cost me a bit of time on the leaders, but I got most of it back through the Esses - the M23 appeared to be getting through the big, fifth gear loop at the end of the straight better than anyone else. By the end of the next straight I was right with the bunch, and it was then just a matter of picking them off bit by bit. James Hunt eliminated himself at the hairpin - all I could see was an airbox spinning off through the long grass.

Everyone else was left racing for second place in his wake. Ronnie Peterson held the position in his Lotus until brake trouble obliged him to move aside and let Denny move up. In the meantime, Emerson Fittipaldi had lost his initial third place when a spark-plug lead came adrift and he'd spluttered into the pits to have it replaced. He shot back out to rejoin, but within a few laps his M23's Cosworth-Ford engine abruptly cut out. He coasted to a halt, unsnapped his seat belts and began to climb out before he recognised the problem: he had inadvertently knocked off the ignition switch (on the M23's steering wheel) while changing gear! He flicked it on, restarted the engine - they had onboard starter systems in those days - but then had to call at the pits again to have his seat belts refastened. Behind Reutemann, Hulme and Hailwood in their McLaren M23s were running second and third until a leaking radiator forced 'Mike the bike' to ease back, allowing the Ferraris of Niki Lauda and Regazzoni to go past. "I was watching pit signals telling me that Niki had closed to within about five seconds," said Hulme, "but I stabilised the gap and held without too much effort."

The Brabham's airscoop shifted to a rakish angle without falling off completely, but then, more seriously, a plug lead came away from the distributor and Denny began to gain. "On the penultimate lap I breezed by. That was sweet - I was leading a GP with just a lap to go, and since I'd already more or less made up my mind that this would be my last year before retirement, I was happy to take the win any way it came." Thus Denny Hulme, the 1967 Formula One World Champion, won the 1974 Argentinean Grand Prix. Lauda took second for Ferrari. On the final lap, Carlos Reutemann's engine cut dead completely and long-suffering Argentinean marshals silently pushed it, and its stony-faced driver, on to the grass. Back in 1974, as now, there was nothing fair about motor racing. But Denny Hulme was not complaining: in sport, you make your own luck.

|

| Doug Nye | © 1999 Atlas Formula One Journal. |

| Send comments to: comments@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |

The article appears courtesy of TAG-McLaren Communications Office | |

It was Denny Hulme's final year of racing in F1, so when he saw a chance for one last win before retirement he didn't hesitate...

It was Denny Hulme's final year of racing in F1, so when he saw a chance for one last win before retirement he didn't hesitate...

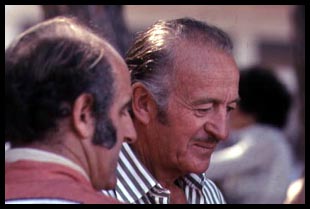

The start in those

days was signalled by flag; and the flagman at that race was none other

than five-times World Champion, Juan Manuel Fangio. Denny approved:

"Fangio didn't mess about with the flag, because he is an ex-race driver,

and he knew that these race car engines got damned hot if they're not

moving through the air. Even so, once we were on the grid, I had to take

it out of first gear for 10 seconds."

The start in those

days was signalled by flag; and the flagman at that race was none other

than five-times World Champion, Juan Manuel Fangio. Denny approved:

"Fangio didn't mess about with the flag, because he is an ex-race driver,

and he knew that these race car engines got damned hot if they're not

moving through the air. Even so, once we were on the grid, I had to take

it out of first gear for 10 seconds."

"Meanwhile Carlos

Reutemann had made a fantastic break and gone. It was his home track, and

he had a really good engine." In fact, Carlos was zooming away into an

ever-increasing lead. His fellow countrymen roared themselves hoarse,

chanting his nickname "Lole, Lole".

"Meanwhile Carlos

Reutemann had made a fantastic break and gone. It was his home track, and

he had a really good engine." In fact, Carlos was zooming away into an

ever-increasing lead. His fellow countrymen roared themselves hoarse,

chanting his nickname "Lole, Lole".

At two-thirds race

distance, Reutemann struck trouble. His Brabham's engine airbox started to

disintegrate and the Brabham designer/team manager Gordon Murray knew that

without an effective airbox, he would lose 200rpm down the long straights.

But his advantage over Denny was 30 seconds - there was time in hand.

At two-thirds race

distance, Reutemann struck trouble. His Brabham's engine airbox started to

disintegrate and the Brabham designer/team manager Gordon Murray knew that

without an effective airbox, he would lose 200rpm down the long straights.

But his advantage over Denny was 30 seconds - there was time in hand.