|

|

| The Best of the Best | |

| by Barry Kalb, Hong Kong | |

|

Atlas F1 is proud to present a series of features on the all-time greatest drivers of Formula One, written by veteran journalist Barry Kalb.

This week's feature: The Pre-War Drivers In almost any racing season, there are one or two drivers who possess that extra amount of drive, that extra bit of racing sense, and above all - that extra bit of innate physical ability, that put them a cut above the rest. Year in, year out, these men will give their all virtually any time they step into a racing car; they will dominate a season when they are in a good car, and produce wins nobody thought possible in a mediocre car; they will turn in performances that racing aficionados talk about for decades to come. It's not enough just to be fast: plenty of drivers are fast in a given race or a given car. But they rarely win, and very often they don't even finish. Drivers such as Jean Alesi or the late Jean Behra fall into this category. The truly great drivers have what Stirling Moss, who is most decidedly one of them himself, once described as "the indefinable quality I call race-winningness." Nor is enough just to win. Ten men have won more than 20 world championship grand prix races in their careers, yet of those ten, only five can indisputably be said to rank among the all-time greats. Drivers like the other five, including two of the winningest drivers in history, may become champion when they have the best car (and not even then in all cases), but they lack the spark of greatness; in some cases, put them in a second-rate car, and they fade into the pack, they even stop trying. A case in point was the miserable performance of Damon Hill in 1997, who stepped down from Williams to Arrows after winning the '96 championship, and turned in only one creditable drive the entire year. It is not even enough to be world champion. Quite a few champions, good as they were - men such as Nelson Piquet, or Jack Brabham, for example - were clearly not great drivers. And Stirling Moss, who every expert ranks among the best, never won the championship. There will always be disagreement in any sport over who was the greatest of all time, especially when athletes competed during different eras. Some people may argue that the following list is incomplete, that Alain Prost or Nicki Lauda or Alberto Ascari, for example, should be included. Perhaps there should be additions. But few people who know motor racing will suggest that the nine names that will be featured in the following articles, should not be there. If nothing else, statistics tell the story. In the matter of wins per start, poles per start, points per start, podium finishes per start, these are the men who stand at the pinnacle of their sport.

Enzo Ferrari raced against Nuvolari in the '20s, and later hired him to drive Alfa Romeo and Ferrari automobiles. Ferrari's involvement with motor racing and racing cars lasted 60 years, giving him a unique perspective on the sport and its participants. In his autobiography, "Ferrari 80", he ranked Nuvolari, along with Stirling Moss, as the all-around best the world had ever seen:

"...We find similar the styles of a Nuvolari and a Moss, men who in whatever type of car, in any type of circumstance and on any race course, give their all... I think of these two pilots because they seem to me to have personified the maximum expression of unqualified ability aboard a vehicle... whether they were piloting a closed car, a two-seater spyder, or a single-seater..."

Nuvolari is credited with perfecting the controlled four-wheel drift, the dominant method of cornering through the early 1960s, until modern suspensions, and later down-draft technology, changed the cornering characteristics of racing machines. He raced against the best drivers of his era in cars good and not-so-good, and he beat them all at one time or another. One of his greatest triumphs was his victory in the 1935 German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring in an aging Alfa-Romeo: through sheer driving skill, he beat the all-conquering and vastly more powerful Mercedes-Benzes and Auto-Unions.* His winning record during the '34-'39 period was second only to that of the German ace, Rudolf Caracciola. Nuvolari came second in the 1947 Mille Miglia after leading most of the way in an under-powered Cisitalia, and would have won the race had he not drowned the ignition going through a puddle, necessitating a 20-minute stop to get the car going again. Nuvolari won almost 200 races during his incredible career. When asked if racing did not frighten him, he replied: "Tell me, do you think you will die in bed? You do? Then where do you find the courage to get into it every night?" He died in bed in 1953. *The old 14.2-mile-long Nurburgring was perhaps the supreme driver's circuit, one of the very few places where the man could be more important than the car, where greatness was allowed to show itself. Moss duplicated Nuvolari's 1935 feat at the 'Ring in 1961 in a year-old, privately-owned Lotus, beating factory Ferraris that could run away from him on the straight. Juan Fangio's most magnificent win came at the Nurburging in 1957, a comeback victory after a long pit stop over the Ferraris of Mike Hawthorne and Peter Collins. Jackie Stewart rated his 1968 win at the track, in appallingly wet conditions, as the best drive of his career.

A bad crash at Monte Carlo in 1933 shattered his right hip and almost ended his career, but he eased back into racing in 1934, the year the new 750kg formula revitalized grand prix racing, and the awesome "Silver Arrows" of Mercedes and Auto-Union first made their appearance. Caracciola won the first European Championship, in 1935. He won the championship again in '37 and '38. He had 15 Grand Prix wins during the '34-'39 period, the most by far of any driver. His final win came at the Nurburgring in 1939, when he won the German Grand Prix for the sixth time.

Alfred Neubauer, the legendary Mercedes team leader and one of the few men who could equal Enzo Ferrari in motor racing knowledge, might have been biased towards a countryman and a driver with whom he shared Mercedes's glory years, but he said of Caracciola:

"...of all the great drivers I have known - Nuvolari, Rosemeyer, Lang, Moss or Fangio - Caracciola was the greatest of them all."

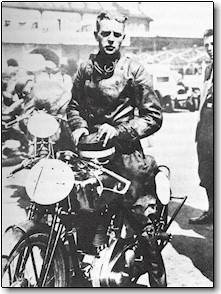

Yet Rosemeyer was such an immediate and spectacular success that there is little room to doubt his greatness. He came to Auto-Union straight from several years on motorcycles, a novice to car racing. It was suggested that the handling characteristics of the mid-engined Auto-Union were so unusual that only someone who didn't know how a car was "supposed" to handle could master it.

He won the European Championship in 1936 with five wins, including another exceptional race at the Ring: halfway through that race fog blanketed the track, and slowed everyone dramatically. Everyone except Rosemeyer, that is, who hardly slowed at all. At one point, he was lapping an incredible 30 seconds faster than the great Nuvolari. To Caracciola's Regenmeister, he became der Nebelmeister - the fog master. In all, Rosemeyer won 10 out of 33 championship starts, a better wins-per-start ratio than either Caracciola or Nuvolari. His greatness was beyond dispute. As author Chris Nixon wrote in "Racing The Silver Arrows", the story of that golden 1934-'39 era:

"...Bernd Rosemeyer was a true phenomenon - a racing driver of genius."

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Barry Kalb | © 1999 Atlas Formula One Journal. |

| Send comments to: bkalb@asiaonline.net | Terms & Conditions |

Barry Kalb is a veteran journalist of 20 years' experience (the Washington Star, CBS News, Time Magazine) and a motor racing fan - especially Formula One - for almost 40 years. He currently resides in Hong Kong. | |

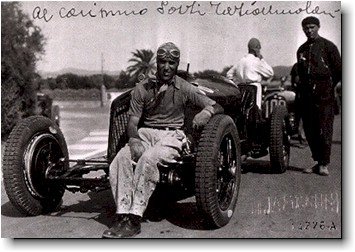

The first name on anybody's list of the greatest is Tazio Nuvolari, the legendary, lantern-jawed, ferociously intense man of Mantova. Nuvolari's racing career, which started with motorcycles, spanned the three decades from 1920 to 1948. The Italian drove during both the pre-war and post-war eras, and unlike most top-rank drivers, who taper off in their latter years of competition, Nuvolari was almost as much a threat at the end as he was at the start. He had already raced for 14 seasons when the golden era of pre-war racing - the 1934-39 period - began, and still he racked up 11.5 grand prix wins during that period (fractional points were given for shared drives). During his next-to-last year of racing, when he was 55 years old, he almost won the fabled Mille Miglia.

The first name on anybody's list of the greatest is Tazio Nuvolari, the legendary, lantern-jawed, ferociously intense man of Mantova. Nuvolari's racing career, which started with motorcycles, spanned the three decades from 1920 to 1948. The Italian drove during both the pre-war and post-war eras, and unlike most top-rank drivers, who taper off in their latter years of competition, Nuvolari was almost as much a threat at the end as he was at the start. He had already raced for 14 seasons when the golden era of pre-war racing - the 1934-39 period - began, and still he racked up 11.5 grand prix wins during that period (fractional points were given for shared drives). During his next-to-last year of racing, when he was 55 years old, he almost won the fabled Mille Miglia.

Ferrari added: "Numerous other racers of great fame, who otherwise demonstrated - like Fangio - sublime class in single-seaters, revealed uncertainty whenever they changed to different types of vehicles."

Ferrari added: "Numerous other racers of great fame, who otherwise demonstrated - like Fangio - sublime class in single-seaters, revealed uncertainty whenever they changed to different types of vehicles."

Caracciola was a German of Italian ancestry, Mercedes-Benz's great pre-war champion. His first major race was the German Grand Prix at Avus in 1926, and he won it in a driving rain. He won the first race held at the Nurburgring, a sports car event in 1927. He won the 1931 Mille Miglia, the only non-Italian aside from Moss (in 1955) ever to win that classic test of skill and endurance. He was called "der Regenmeister" (the rain master) because of his incredible ability to drive faster than everybody else in the wet - an ability later demonstrated by Moss, Clark, Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher.

Caracciola was a German of Italian ancestry, Mercedes-Benz's great pre-war champion. His first major race was the German Grand Prix at Avus in 1926, and he won it in a driving rain. He won the first race held at the Nurburgring, a sports car event in 1927. He won the 1931 Mille Miglia, the only non-Italian aside from Moss (in 1955) ever to win that classic test of skill and endurance. He was called "der Regenmeister" (the rain master) because of his incredible ability to drive faster than everybody else in the wet - an ability later demonstrated by Moss, Clark, Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher.

Caracciola sat out World War II in Switzerland, and then resumed driving for a while after the war. He finished fourth in the 1952 Mille Miglia, but for the most part his post-war career was lackluster and punctuated by serious accidents. Later in '52, he crashed during a sports car race in Bern, smashing his left hip, and finally ending his racing days at the age of 51. He died a natural death in 1959.

Caracciola sat out World War II in Switzerland, and then resumed driving for a while after the war. He finished fourth in the 1952 Mille Miglia, but for the most part his post-war career was lackluster and punctuated by serious accidents. Later in '52, he crashed during a sports car race in Bern, smashing his left hip, and finally ending his racing days at the age of 51. He died a natural death in 1959.

The only argument one could make for not placing Bernd Rosemeyer among the all-time great drivers is the shortness of his career. He drove the great, fire-breathing Auto-Unions for only two and a half seasons, 1935-'37, before being killed during a world land speed record attempt in January 1938. Normally, that would be too short a time to assess a driver's ability.

The only argument one could make for not placing Bernd Rosemeyer among the all-time great drivers is the shortness of his career. He drove the great, fire-breathing Auto-Unions for only two and a half seasons, 1935-'37, before being killed during a world land speed record attempt in January 1938. Normally, that would be too short a time to assess a driver's ability.

Rosemeyer, in any event, mastered the car magnificently: in his first race, the 1935 Eifel Grand Prix at the Nurburgring, he passed the great Caracciola and led the race until just before the very end, when Caracciola re-passed him to win by a scant 1.8 seconds. He had another second that year at Pescara, and two thirds, and then won his first grand prix in Czechoslovakia at the end of the season.

Rosemeyer, in any event, mastered the car magnificently: in his first race, the 1935 Eifel Grand Prix at the Nurburgring, he passed the great Caracciola and led the race until just before the very end, when Caracciola re-passed him to win by a scant 1.8 seconds. He had another second that year at Pescara, and two thirds, and then won his first grand prix in Czechoslovakia at the end of the season.