|

He is Lancelot to his teammate's Arthur. Or Han Solo to his Luke Skywalker, if you prefer movies to medieval poetry.

Whatever metaphor you choose, one thing is certain: as Michael Schumacher's on-track support system, Eddie Irvine has labored thanklessly behind his teammate, keeping his pursuers at bay so that Ferrari's Teutonic hero might grasp the World Championship.

The trouble is, time and again, Schumacher has proven himself not up to the hero's task. Last year at Jerez and again this year at Suzuka, he has failed in spite of his teammate's steady support. From his inexcusable tirade at David Coulthard in Belgium, to his arrogant pre-Suzuka statement that he would let Irvine win "if Hakkinen is no longer in the race," it is becoming increasingly obvious that Schumacher, like so many mythic heroes, suffers from the familiar tragic flaw of excessive ego. The trouble is, time and again, Schumacher has proven himself not up to the hero's task. Last year at Jerez and again this year at Suzuka, he has failed in spite of his teammate's steady support. From his inexcusable tirade at David Coulthard in Belgium, to his arrogant pre-Suzuka statement that he would let Irvine win "if Hakkinen is no longer in the race," it is becoming increasingly obvious that Schumacher, like so many mythic heroes, suffers from the familiar tragic flaw of excessive ego.

But, behind all the media focus on the German's blustering self-aggrandizement, a subtle breeze has begun to blow around the circuits of Formula One. Something the press has given only the slightest nod to, and something Ferrari hasn't even publicly acknowledged.

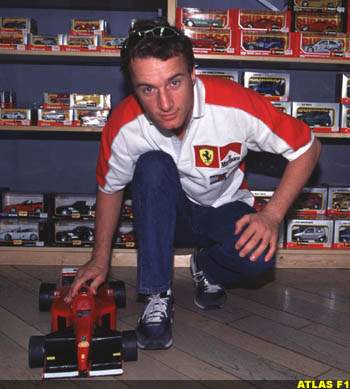

Eddie Irvine, a man once described as "reckless," "inconsistent" and even "disappointing," has quietly come into his own in 1998.

True, he has yet to win his first Grand Prix. But this can largely be attributed to the fact that his "arrangement" with Ferrari compels him to let Schumacher by if the German is in any position to win a race. Who knows what might have happened to Irvine's fortunes had he not sacrificed himself over and over to grant Schumacher a better position? He slowed up to let Schumacher by at Imola, and kept Hakkinen away from him in Montreal. He managed to run a similar kind of interference for his teammate at Magny-Cours, despite severe downshifting difficulties and a lake of oil on the track. And, of course, there was that dubious, uh, "brake failure" in Austria. However, Irvine gallantly demonstrated in race after race after race that he didn't mind this role.

Alas, all was not well in il Cavallino's paddock, despite outward appearances. Irvine's increasing frustration with his assignment began to bubble over in July at Silverstone, when he told Peter Windsor that he didn't join F1 to lose and that he felt he deserved to be an "equal number one" to Schumacher. Rumors began to fly that Schumacher's support structure was searching for a seat elsewhere. This frustration was almost certainly exacerbated by the fact that Irvine's self-professed goal for the 1998 season was to reach the top of the podium--a goal that Ferrari completely eclipsed in their madness to earn the title for Schumacher. Luca di Montezemolo's pledge to finish what Ferrari and Schumacher started next season has served to re-awaken Irvine's discontent, as his response to Ferrari's post-Suzuka promise indicates: "My chances of having a shot at the title or racing with Michael for victory are wrecked. It will now be the same deal, which means another year of helping Michael. It's not a nice experience and I wouldn't wish it on anyone."

Irvine, of course, is not Schumacher. The Irishman is still prone to careless mistakes: spinning off in Belgium, losing the lead in Luxembourg, bumping Fisichella in Spain. However, 1998 showed fewer DNS's for Irvine than ever and he finished well up in the points in all but two of the races that he completed. He also landed on the podium an unprecedented eight times - no mean feat, considering his spotty record in years past.

During the 1998 season, Irvine has demonstrated a steady increase in his skill and control. The start of the season was rather unremarkable for him, as he finished only fourth in Australia and eighth in Brazil. However, the next seven races saw him finish on the podium six times--as many as he earned in 1996 and 1997 together. He had a run of bad luck during the next few races - clearly his own fault in Belgium, and not so clearly in Austria. But for the remainder of the season, his performances continued to show a rather un-Eddie-like consistency and dependability, with two strong second place finishes - one of them behind Schumacher at Ferrari's all-important home Grand Prix at Monza.

By Suzuka, however, doubts were beginning to surface regarding Irvine's fitness when it came to light that he had been suffering from almost continuous back pain throughout the season, and rumors regarding his replacement abounded. A new seat was fitted to allay the problem; however, rather uninspired performances during Friday's free practices and Saturday's qualifying caused even Irvine to say, when asked how he planned to aid Schumacher's win, that "maybe I am the one who needs the help." For the first time in Irvine's career, the eyes of the world were on him, watching to see if he could measure up in this test of all tests: to fend off the sterling McLarens and help Ferrari's German hero earn the necessary points for the World Championship. As the pressure mounted, Irvine was found wanting and he doubted his own capabilities. "My role is the same as it is at every race... Obviously, all the focus is going to be on me trying to beat the McLarens, but I've only managed that twice this year." By Suzuka, however, doubts were beginning to surface regarding Irvine's fitness when it came to light that he had been suffering from almost continuous back pain throughout the season, and rumors regarding his replacement abounded. A new seat was fitted to allay the problem; however, rather uninspired performances during Friday's free practices and Saturday's qualifying caused even Irvine to say, when asked how he planned to aid Schumacher's win, that "maybe I am the one who needs the help." For the first time in Irvine's career, the eyes of the world were on him, watching to see if he could measure up in this test of all tests: to fend off the sterling McLarens and help Ferrari's German hero earn the necessary points for the World Championship. As the pressure mounted, Irvine was found wanting and he doubted his own capabilities. "My role is the same as it is at every race... Obviously, all the focus is going to be on me trying to beat the McLarens, but I've only managed that twice this year."

And so, Sunday dawned, and the world waited to see if Irvine would succeed in his quest to defend his team leader.

No one could have imagined a more shocking outcome. Not even Schumacher, with his pre-race premonitions that "something special" would happen at Suzuka, could have had this story in mind.

After two false starts, suddenly Irvine found himself third on the grid, with Schumacher eight rows behind. Ferrari's utter incomprehension of this possibility was revealed by Irvine after the race: "We had looked at every possibility except me at the front and Michael at the back." But, after the carbon dust cleared from the grid, Irvine showed the mark of the truly skilled professional: he made an instantaneous, independent, decision and was able to flex the plan to fit the situation. "It was strange to have Michael starting from the back of the grid, because suddenly I realized that it was down to me. I knew I had to get stuck in - it was almost like flicking a switch - and I made a fantastic start."

From that point on, the Japanese Grand Prix was all about Hakkinen and Irvine. True, Schumacher's charge from the back of the crowd was awe-inspiring up to the point of his tire failure, but let's face it: his shot at the championship was lost the minute his car stalled. And the rest of the field - including the usually ironclad David Coulthard (a brave supporting act in his own right, to be sure) - faded into obscurity. Eddie, it was clear, was aiming for his first win and proceeded to drive the cleanest, most serene race of his 1998 season. Only tire problems and his redundant three-stop strategy (ironically engineered to support the absent Schumacher) kept him from achieving his goal.

On the overall poetic scheme of things, of course, it was only right that the day and the race, should belong to Hakkinen. But Irvine crossed a threshold of his own at Suzuka. We saw him - and, more importantly, he saw himself - as something more than a prop for his double-World-Champion teammate.

Ferrari would do well to have a similar vision for him in 1999. After all, as long as the Prancing Horse wins, does it matter who rides him across the finish line?

|