1964: Racing The Way It Ought To Be

One of Clark's many rewards in 1963 was that he was featured on the cover of Time magazine, certainly a watershed accomplishment, then or now, for a mere Grand Prix driver.

The 1964 season proved to be more competitive than 1963, with Ferrari, Brabham, BRM and Lotus winning races and the Championship going down the wire to the last race in Mexico, with Clark, Surtees and Hill still in contention.

Indeed, in some ways the 1964 season is about as good a snapshot of what Grand Prix racing should be as you will ever find - it was international, the cars were beautiful, the rear-engined/monocoque technology was established but still evolving, both V12 and V8 engines were being used, the racing was competitive and the drivers were a brave and interesting lot. Honda, which it must be remembered was then still regarded as a motorcycle manufacturer which had only recently developed a modest sportscar, entered the Grand Prix fray (at the Nurburgring of all places), with the Honda RA271, an ear-splitting transverse-mounted V12, with American Ronnie Bucknum at the wheel, painted all white with a bright red rising sun on the scuttle. The BRM of that time, which epitomized the season was the monocoque BRM P261 V8, the svelte, deep green car with the orange stripe around its nose and Graham Hill's distinctive helmet, goggles and mustache peering out of the cockpit.

Australia's Jack Brabham had been fielding his own cars since 1962, but in 1964 would finally get his first victory, when on June 28, 1964, his driver Dan Gurney finished first in the French Grand Prix at Rouen in his tubular spaceframe Brabham-Climax BT7. Dan won again for Brabham in Mexico City in the last race of the season on October 25, 1964. This was also a time when short-nosed variants were developed by some of the constructors, giving rise to the snubbed nose BT7 especially designed by Brabham for the streets of Monaco, as Vanwall and Ferrari had done in the late 1950's.

Another unique feature of the 1964 season was that Ferrari, as a result of one of its periodic tiffs with the Italian racing authorities, departed from its traditional Blood Red paint scheme for the Grands Prix in North America, where the Ferrari 158 Aero V8 sported the blue and white American colors of NART, the North American Racing Team run by Luigi Chinetti, Ferrari's main man in the States.

As to drivers, 1964 was a crossover year: older drivers like Maurice Trintignant, then 47 years old, retired. Trintignant had begun his career in modern Formula One's first season, 1950, racing in the 1950 Monaco Grand Prix against the likes of Fangio, Farina, Ascari, Etancelin, Chiron, Sommer, Bira and Schell, a link with the Ghosts of Grands Prix Past. Phil Hill, World Champion with Ferrari in 1961, did not formally retire in 1964 but drove his last Grand Prix that year in Mexico City, driving the uncompetitive Cooper-Climax as a teammate to Bruce McLaren. By contrast, emerging drivers like Austrian Jochen Rindt and Swiss Jo Siffert were making themselves known in 1964 and Jackie Stewart showed up at a practice session for the British Grand Prix in mid-season and, with the help of fellow Scot Jim Clark, tried out Jimmy's spare Lotus 33 around Brands Hatch. Graham Hill, John Surtees and Dan Gurney and Lorenzo Bandini were all beginning to hit their stride.

And then of course there was Lotus and Jimmy Clark, running first the Lotus 25 and later on in the year the improved version, the Lotus 33. The 1964 Championship season began at Monaco on May 10, 1964, where Clark qualified on pole, was 3 seconds ahead of Brabham on the first lap and was to lead for the first 30 laps of the 100 lap race. But then handling problems developed when he damaged his rear anti-roll bar. After stopping in the pits for a check of the car, he was off again, embroiled in a three-way battle among Gurney, Graham Hill and Clark, which ended when Gurney and Clark had mechanical troubles, leaving Hill and BRM teammate Richie Ginther to finish first and second, Clark finishing fourth.

Less than a week later, on Saturday, May 16, 1964, Clark and Gurney were "Back Home in Indiana" with the Indianapolis Lotus Ford 34's where during qualifying Clark took pole position at 158.825 mph. Jack Brabham joined Clark and Gurney on this transatlantic extravaganza, with Brabham driving the Zink - Urschel Trackburner, a rear-ended Offenhauser-powered special designed by Brabham's friend and fellow Australian Ron Tauranac, who would later on run and own the Brabham Formula One team before selling it to Bernie Ecclestone.

Less than a week later, on Saturday, May 16, 1964, Clark and Gurney were "Back Home in Indiana" with the Indianapolis Lotus Ford 34's where during qualifying Clark took pole position at 158.825 mph. Jack Brabham joined Clark and Gurney on this transatlantic extravaganza, with Brabham driving the Zink - Urschel Trackburner, a rear-ended Offenhauser-powered special designed by Brabham's friend and fellow Australian Ron Tauranac, who would later on run and own the Brabham Formula One team before selling it to Bernie Ecclestone.

Having vanquished the regulars during time trials at the Brickyard on May 16th, Clark and his fellow travelers were back in Holland by Sunday, May 24, 1964, for the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort, where Gurney took pole position in his Brabham-Climax, and Clark set fastest lap and won by over a minute over John Surtees in the Ferrari 158: Gurney's steering wheel broke and he was out after 23 laps of the 80 lap race.

After Zandvoort, it was back across the Atlantic to Indiana for the traveling trio where, on Saturday, May 10, 1964, a horrific and fatal accident on lap 2 marred the 1964 Indy 500, killing Indy veteran Eddie Sachs and Indy rookie Dave MacDonald, knocking 7 cars out of the 33 car field and stopping the race for nearly 2 hours. Clark, Gurney and Brabham were clear of the crash.

It was unprecedented for an Indy 500 to be red-flagged and the way Clark composed himself as the dimensions of the tragedy became known was revealing of the incredible coolness of his demeanor. When the accident happened, Dave MacDonald's rear-engined gasoline-powered Mickey Thompson-Ford hit the wall on Indy Turn 4 and burst into flames, which spread across the entire 50 foot width of the track, creating a wall of fire just beyond the point where Turn 1 now is for the U.S. Grand Prix at Indy.

Characteristically, Clark had gotten a jump on the field as the white Ford Mustang pace car pulled off, setting record laps in his first two laps. Clark was already in Indy Turn 1 when the accident happened (the Indy 500 is run counterclockwise) and at an average speed of 154 mph Clark's Lotus arrived on the scene in short order, as the yellow lights came on and a huge plume of thick black smoke enveloped the Speedway, reducing visibility to zero at the scene of the crash. Clark came to a halt briefly and then slowly led the 26 remaining cars through the smoke, dodging burning cars and firefighters who were already on the scene.

According to the late Andrew Ferguson's account of this scene in his fabulous book, Team Lotus, The Indianapolis Years, after threading his way through the melee, Clark pulled his car to a stop, released his seat belts and slowly climbed out of the Lotus-Ford, sitting down on the surface of the track to await the restart, creating a makeshift backrest for himself by leaning back on his left front wheel next to the left side of the cockpit and the "Lotus Powered by Ford" stenciling, trademark dark blue Bell helmet and gloves still on, face still taped up to protect against stones and dirt, surrounded by Lotus-Ford crew members, who sat or kneeled around Clark, assessing his reaction to the horrors he had just witnessed and driven through. Jimmy read the looks of concern on the crew's faces and called Ferguson over and in an attempt to reassure everyone said: "Don't look so worried, it's only a sport."

Clark's philosophic and perhaps fatalistic view of motor racing would come in handy later on. After the race was restarted, Clark was back in the lead when, on lap 47, while in Indy Turn 4 at speed, his left rear Dunlop tire shredded which caused the suspension of the Lotus to collapse just as the car passed the Yard of Bricks. Clark brought the car to a halt in Indy Turn 1 and parked it. Again, Clark was outwardly unflappable, first asking to borrow Ferguson's Lotus Elan so he could leave the racetrack and then chatting up a girl Clark had spotted in the crowd and had befriended. As Ferguson watched, Clark and his Lotus Elan disappeared into Speedway, Indiana, Clark "[s]till in his overalls, and having put his crash helmet in the boot of the Elan, he drove off, accompanied by his friend."

While Clark was now free of the dangers of that ill-starred Indy 500, Gurney was still out there on the suspect Dunlop tires. By lap 96 of the 200 lap race, Gurney was up to fifth after making an ill-judged pit stop early in the race, and came into the pits for tires and fuel. After the pit stop, Colin Chapman examined the treads of the worn tires and detected signs of the chunking problem that had plagued Clark. Chapman gave the order to call in Gurney, ending Lotus-Ford's second attempt to win Indy, much to Ford's displeasure since it was Chapman who chose the British Dunlop tires over the American Firestone tires Ford would have preferred. The 1964 Indy 500 was the last Indy 500 won by a front-engined car, the Sheraton-Thompson Special driven by A.J. Foyt and running on Firestones.

As if Clark and Gurney had not had enough excitement for the summer of 1964, the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa on June 14, 1964 threw them back together again as they battled along with Graham Hill's BRM and Bruce McLaren's Cooper in the closing laps in one of those races where it appeared that no one wanted to win. Gurney in the Brabham-Climax BT7 was on pole, set fastest lap (137 mph) and had led laps 4-29 of the 32 lap race, when he heard the engine coughing and came into the pits for fuel. As happened to Gurney at Indianapolis 20 days earlier, it was an improvident pit stop because the Brabham pit had no fuel ready to give to Gurney. By the time Gurney had rejoined the race, Graham Hills BRM P261 was in the lead and Bruce McLaren's Cooper-Climax T73 was in second place, with Clark still behind Gurney, Clark having himself been delayed 30 seconds by pitting to add water to cool down the Lotus.

In the final lap of the 8.76 mile circuit, where it took about 3 minutes and 50 seconds to complete a lap, a concatenation of events unfolded that left all who were there dumbfounded. Hill's fuel pump in his reserve gas tank failed while he was still in the lead and he coasted to a halt. Then McLaren's Cooper died with electrical problems at the final corner, which was then the La Source hairpin, while leading, McLaren hoping literally to glide downhill from La Source to the finish line. Gurney had in the meantime used up his remaining fuel and stopped further back on the circuit at Stavelot, unable to overtake McLaren. Which left Clark, who passed McLaren after seeing him limping around La Source, thus winning the race, his third victory at Spa.

But Clark did not know he had won the race. And in the course of his cool down lap, Clark also ran out of fuel, coasting in to join his friend Gurney at Stavelot. Luckily for us, photographers captured this moment at Stavelot, where Clark, still in his car, looks quizzically up at a smiling Gurney who was now standing at Stavelot corner outside of his Brabham, Clark clearly asking, "So, who won."

But Clark did not know he had won the race. And in the course of his cool down lap, Clark also ran out of fuel, coasting in to join his friend Gurney at Stavelot. Luckily for us, photographers captured this moment at Stavelot, where Clark, still in his car, looks quizzically up at a smiling Gurney who was now standing at Stavelot corner outside of his Brabham, Clark clearly asking, "So, who won."

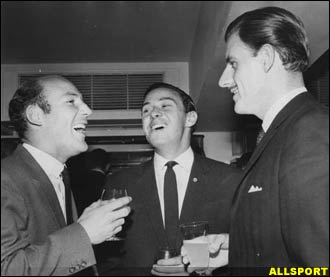

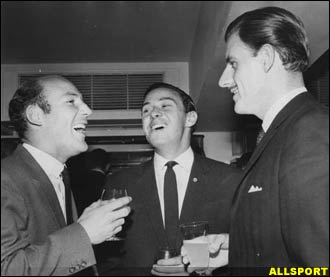

By the time Clark clambered out of the Lotus, the loudspeakers announced that Clark had won and Grand Prix photographer Geoff Goddard's sequence of pictures in his book Track Pass which capture Clark's astonishment, joy and beaming smile upon hearing the announcement are a window into Clark's character and the relationship between Gurney and Clark, rivals but friends. Befitting Clark's victory, Lotus teammate Peter Arundell stopped at the Stavelot corner to pick up Clark who rode to the victory rostrum on the back of Arundell's Lotus, astride the engine cover of the Climax engine, holding on to the roll bar hoop. Gurney walked back to the pits, another fine race torpedoed by the Fickle Finger of Fate.

The next race, the French Grand Prix at Rouen on July 28, 1964, would go to Gurney, who was second on the grid to Clark who had qualified on pole. Clark led until retiring on Lap 31, leaving Gurney's Brabham in the lead with Graham Hill's BRM breathing down his neck, finishing only seconds behind Gurney and just ahead of Jack Brabham, appropriately the Brabham team's first win. France seemed to be Gurney's lucky venue; he won at both Rouen and Rheims and had his 1961 slipstreaming battle with Baghetti at Rheims as well.

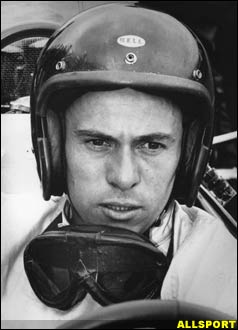

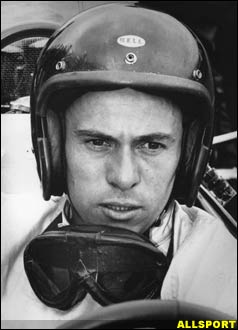

Brands Hatch hosted the British Grand Prix for the first time in 1964, where Clark and Hill qualified first and second and dueled throughout the race, only to finish as they began, Clark winning by a few seconds. But just before the 1964 British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch got underway, we got something of a glimpse into the duality of Clark's personality: cool, calm and collected at the wheel of his Grand Prix car but a shy, fingernail biting bundle of nerves outside the cockpit.

As the cars were being readied to be moved from the "dummy" grid to the real grid, all eyes were on Clark's Lotus 25, whose Climax engine was balking, which manifest itself during the reconnaissance laps. Clark sat in the cockpit, light blue Dunlop overalls and dark blue helmet with white brim on, goggles off, trying to look his imperturbable self for the cameras while his Lotus mechanics feverishly changed and tightened the spark plugs to the temperamental engine before the cars were ordered to the grid. Color footage of the race shows Clark's eyes darting back and forth looking first at his left mirror, then at his right, watching the progress of his mechanics in changing the plugs, ultimately pursing his lips as the engine cowling is put back on in time, then looking forward stolidly pinching his nose and pursing his lips, as if to say, "Right, then, that will have to do, let's hope this thing holds together for a change."

The opening laps of the 1964 British Grand Prix were a virtual summary of the 1960's. Clark started with a little wheelspin, Gurney to his outside getting the better start and coming alongside Clark at Druids challenging the Lotus there and in the first few corners of the opening lap until Clark established himself in first place, with Gurney in the Brabham and Graham Hill in the BRM tucked in right behind him. But again, as was typical of the era and of these two men, within a few laps, Gurney's hand went up to indicate a problem (this warning narrowly avoided his being hit by Surtees); Gurney slowed and headed back to the pits with the ignition system smoking.

Back in the pits, Gurney got out of the car and tried to discourage a fireman from dousing the whole car because Gurney sensed that the car was salvageable, but Gurney didn't yell at the poor fireman, just calmly explained that it was only a little electrical fire. In another revealing moment, Gurney stood toward the rear of his car, helmet still on and at the ready, resting his long right foot atop the left rear tire, anxiously waiting for the mechanics to change the rectifier, which took them four laps. Next to him, ever at the center of the action, stood Stirling Moss, now a commentator for ABC News, an American television network, following his career-ending accident at Goodwood in 1962. Such was the tension in the air that Moss and Gurney stood side by side, both intently watching the repairs, almost as if Moss were still a driver, no thought of Stirling doing a "so what's wrong with the car, Dan" interview.

Graham Hill was able to keep Clark in his sights in the elegant orange-nosed BRM P261, gradually catching Clark up after 8 laps in a thrilling nip and tuck battle until the BRM began to slow after 29 laps due to oil pressure surges in the corners, allowing Clark to extend his lead over Hill up to seven seconds. Towards the end of the race, Hill closed the gap and mounted one last challenge, to which Clark responded by posting the fastest lap of the race, ultimately crossing the finish line 2.8 seconds ahead of Hill in a race that epitomized an era.

By the time of the German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring on August 2, 1964, the reliability of the Ferrari engines was coming to the fore and Surtees finished first with teammate Lorenzo Bandini in third, Clark having gone out with engine problems at half-distance.

In a non-Championship race called the Mediterranean Grand Prix held on August 16, 1964, at the fast Enna-Pergusa circuit laid out around Lake Pergusa in Sicily, Clark found himself challenged as a driver for one of the few times in his career. Surprisingly, Swiss privateer and relative newcomer Jo Siffert outqualified the Lotuses in his Brabham BT11-BRM and fought a nerve-racking wheel-to-wheel slipstreaming duel with Clark around Lake Pergusa, with Innes Ireland in a BRP-BRM swapping the lead with Siffert and Clark for part of the race.

In a non-Championship race called the Mediterranean Grand Prix held on August 16, 1964, at the fast Enna-Pergusa circuit laid out around Lake Pergusa in Sicily, Clark found himself challenged as a driver for one of the few times in his career. Surprisingly, Swiss privateer and relative newcomer Jo Siffert outqualified the Lotuses in his Brabham BT11-BRM and fought a nerve-racking wheel-to-wheel slipstreaming duel with Clark around Lake Pergusa, with Innes Ireland in a BRP-BRM swapping the lead with Siffert and Clark for part of the race.

In the end, Clark was beaten fair and square, with the slipstreaming trio finishing as follows: Siffert finished first just 0.1 seconds ahead of Clark who finished 0.8 seconds ahead of Ireland. For a privateer to beat the reigning World Champion was as remarkable an achievement then as it would be now. Ironically, almost a year to the day later, Siffert did the same thing, again in Sicily, as he and Clark did a reprise of their 1964 slipstreaming struggle, Siffert once again besting Clark. So, the Great Scot could be beaten on occasion it seems, with lightening striking twice in the case of Jo "Sicily" Siffert, but it did not happen too often.

At the next Championship race, the Austrian Grand Prix at the Zeltweg airfield, Bandini won his only Grand Prix in the older V6 Ferrari when his adversaries and their cars shook themselves and their suspensions to bits on the rugged, washboard-like concrete runways.

For the Italian Grand Prix at Monza on September 6, 1964, Ferrari fielded a three-car team to enhance Surtees' growing prospects for the Championship. Surtees qualified on pole and set fastest lap but Gurney was right next to Surtees on the front row and challenged Surtees for the lead until lap 56, when Gurney began to slip back, ultimately finishing tenth. Neither of Surtees rivals - Clark and Hill - finished.

As the Grand Prix teams headed to North America for the U.S. and Mexican Grands Prix, the Championship was heating up and the teams were pulling out all the stops. On October 4, 1964, at Watkins Glen, when Clark's Lotus 33 retired at half-distance with fuel injection problems, Colin Chapman called in Clark's teammate, Mike Spence, and turned that car over to Clark with the express purpose of attempting to deny points to rivals Surtees and Hill; unlike the early days in Grand Prix racing, by 1964, a driver could not score points by co-driving a teammate's car.

In the end the ploy failed and the Spence/Clark Lotus finished seventh, Hill won his third U.S. Grand Prix and the blue and white NART Ferrari of John Surtees finished second, sending the three-way title battle to the last race in Mexico, with Graham Hill having 39 points, Surtees 34 and Jim Clark 30. Gurney's lackluster finishes in the latter half of the season left him well out of the running but he was anxious to finish his season strongly.

In Mexico City on October 25, 1964, Clark and Gurney found themselves once again on the front row for the Mexican Grand Prix. As the race developed, Hill was hit from the rear in a slow turn by Surtees Ferrari's teammate, Lorenzo Bandini, Hill was forced to stop in the pits to repair his crumpled exhaust pipes and was effectively out of the Championship. Clark did all he had to do to take the Championship by leading laps 1 to 63 of the 65 lap race, Gurney lying second; typically, Clark also set fastest lap.

But then Clark's Lotus 33 began to slow due to a loss of oil pressure, with just 2 laps (or four minutes!) to go to retain the World Championship he had won in 1963. In the next to last lap, Gurney got by Clark's limping Lotus in his Brabham to win the race. As Clark continued to circulate, Bandini was the next car up but he let teammate Surtees by so that Surtees could finish in second place behind Gurney and clinch the Drivers' Championship. With Bandini finishing in third, Ferrari also took the Constructors' Championship for 1964. As for Clark, in a repeat of the end of the 1962 season, the oil drained away (this time it was a rubber pipe fracture) and with it went his hope of a back-to-back Championship. But at least this time, in a turnabout from what happened at Spa, Gurney got his due and the victory.