|

| |||

|

Technical Focus: F1 and the Road Car | ||

| by Will Gray, England | |||

|

In a series of articles, Will Gray investigates the input of Formula One on the road car industry, and assesses whether the manufacturers are in it for its marketing or its development potential.

In the late 80's and early 90's, it was Ferrari vs. McLaren in Formula One. At the same time, both brought out road going supercars. Now they're challenging for the championship again, both companies are developing competing road cars. We take a look at the past and the future of the off-track Ferrari-McLaren battles.

Part III: Ferrari

Driven by customers asking why the company could not build something close to a Formula One car that could be driven on the road, the engineers at Ferrari began looking into the areas of their Grand Prix machine which made it just that. The power in their road engines, they decided, was enough, but it was concluded that it would be possible to bring across much of the technology of Formula One onto a road car.

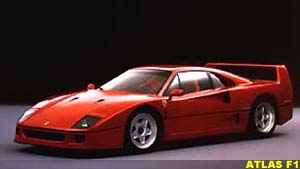

The Ferrari F40 (the car's predecessor) had looked as though it was a carbon fibre chassis, but this was not the case. It was simply a tubular frame chassis with carbon parts.

The second important area is the F50's much acclaimed 'Formula One derived' engine. This is based on the 3.5 litre V12 unit which powered Prost and Nigel Mansell in the 1990 season, but it's relations are loose. The road going powerplant took the F1's 65-degree vee, used the same 5-valve per cylinder design, and retained the block length. Everything else, however, is different. It had to be - although the F50 is a remarkable car, the requirement to replace an engine every 200 or so miles as in an F1 car would be ridiculous! Some of the exotic materials have made it onto the road engine, however, with titanium playing a part in the internals. The capacity was increased to 4.7 litres, and the engine hits the rev limiter at 8,700 rpm, quite some way short of the 14,000 attainable with the F1 engine - pneumatic valve springs made such revs possible, but these were too unreliable to be used due to air leakages (which have been often seen to cause problems in Grands Prix), and were replaced with steel springs for the road engine.

The engine is mounted directly to the carbon fibre monocoque, and this caused problems as carbon fibre is a great transmitter of vibrations and sound. An F1 driver is alright wearing a helmet and earplugs, but Ferrari felt it couldn't demand this of the road car driver! Some modifications were achieved, but the engine remains loud - so Ferrari used its raw, unrefined qualities as a selling point!

Part of this handling equation is the suspension, which is a unique innovation to have come across from Formula One. It uses independant double wishbone suspension, with pushrods connecting to inboard springs and dampers, just as Prost and Mansell's F1 car did. However, in standard road car design, rubber bushes are used to act as cushions at suspension mounting points, and reduce the transmission of road noise. These are to the detriment of handling, and for that reason, they do not exist in F1. There, the suspension is mounted directly to the chassis or gearbox with rigid ball joints (somewhat like a hip joint). Ferrari went with this method for the F50, deciding that as this is an F1 car for the road, handling could not be compromised - besides how could the extra road noise add anything to the sound of that beast of an engine sitting behind the driver! To the surprise of the industry, the suspension was a success, and the ride was not as harsh as expected, but despite this, we have not yet seen any other road cars use this technology.

The only compromises on this car were road legailties and driver limitations, and Ferrari see the F50 as truly an F1 car for the road. However, there are doubts over the future of these supercars, with stricter emissions legislations coming in all the time, so don't expect another monster like this one...unless F1 begins to require eco-friendly engines.

The supercar era is (unofficially) over, and now manufacturers are using F1 developments in more limited fashion. Ferrari's future, in the F360 Modena, shows that even in their 'non-exclusive' range, the F1 involvement comes through. The new car uses traction control, and drive-by-wire technology, as well as the (now mandatory on all sports cars) F1 style semi-automatic paddle gear change. Its performance, although road car bred, has benefited from the thoughts of the racing engine designers. Oh, and the paint job. It still looks best in red!

Previous Parts in this Series: Part I: Improving the Breed | Part II: Improving the Brand

|

| Will Gray | © 2000 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: gray@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |