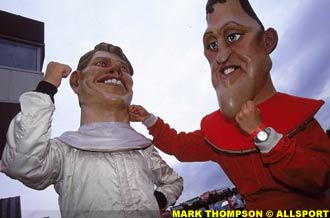

Quick question - which is the most dominant driver-duo of the past twenty years? Senna and Prost in the '88/'89 McLarens, right? Wrong. Senna and Prost won 25 of their 32 starts in those two seasons; since the start of 1998, Michael Schumacher and Mika Hakkinen have started 42 races together (discounting Schumacher's injury period in '99), and have won 33 of those starts. It's only a fraction of a percentage difference, but the Schumacher/Hakkinen rivalry is incredibly the more dominant, compared to the performance of the rest of the field.

Little wonder, then, that the bookmakers' odds refused to countenance the possibility of any other driver winning the 2000 World Drivers' Championship. After the comedy of errors which marked the Schumacher-less second half of last season, 2000 promised to be a momentous year. Whoever triumphed would enter the realm of legend - Schumacher for returning the World Drivers Championship title to Maranello after a 21-year wait, or Hakkinen for becoming the first driver since Fangio to 'three-peat' the coveted crown. In a perfect world, the pair would have dominated as they had in the past. But Formula One has more plot wrinkles (and almost as many lawyers) as a John Grisham novel...

Little wonder, then, that the bookmakers' odds refused to countenance the possibility of any other driver winning the 2000 World Drivers' Championship. After the comedy of errors which marked the Schumacher-less second half of last season, 2000 promised to be a momentous year. Whoever triumphed would enter the realm of legend - Schumacher for returning the World Drivers Championship title to Maranello after a 21-year wait, or Hakkinen for becoming the first driver since Fangio to 'three-peat' the coveted crown. In a perfect world, the pair would have dominated as they had in the past. But Formula One has more plot wrinkles (and almost as many lawyers) as a John Grisham novel...

Ultimately, it was poor timing on Hakkinen's and McLaren's part that sealed the Schumacher triumph. When Hakkinen was on top form, the car proved fragile. And when McLaren sorted out the reliability problem, allowing Hakkinen to record twelve straight trouble-free finishes, the Finn initially suffered a baffling and uncharacteristic slump in form.

In previous era, cars were usually either fast or reliable, seldom both. To win in modern F1, the champion car must have both qualities. Ferrari and McLaren have got it right, to the extent that together they scored nearly three times as many points this year as the rest of the field combined. No other team got even a sniff at a single pole position, let alone a race win. Yet, despite the continuing and lopsided nature of F1 competition, the 2000 season still produced some encouraging signs further down the grid.

Both Williams and BAR started to show the benefits of their associations with BMW and Honda respectively, and Benetton will surely follow suit. It's no coincidence that corporate players filled the top five constructors' slots in 2000, and the gap between the haves and the have-nots will only grow in the future. The nett loser was Eddie Jordan, although the Honda works engine deal for 2001 will have softened the blow. Even the humble Arrows outfit, for so long down at the whipping-boy end of the grid, turned up with an extremely pretty package that was also unbelievably fast in a straight line.

The jostling for position further down the grid held little significance for Ferrari and McLaren. For the whole of the 2000 season, they held centre-stage, bickering over the spotlight like theatrical prima donnas. And while the year's events only heightened the simmering and public hostility between the two giants, it also illustrated the respect which they have for each other's racing pedigree.

Both teams had spent the off-season working on their weaknesses rather than reinforcing their strengths, and statistically it showed. Over the previous two seasons, the Ferrari had been well off McLaren's pace in qualifying, only to claw back some of the deficit in race trim. For Ferrari, handing track position to the McLarens was a failing that could not be reliably countered, even by the tactical acumen of Ross Brawn. McLaren's raw pace advantage was offset in turn by engine and hydraulics fragility - at least three of Schumacher's six wins in 1998 had been gifted by McLaren unreliability.

Ferrari found the qualifying speed they sought, turning the 3-12 pole position deficit of 1998 into a 10-7 advantage in 2000. In return, McLaren improved their reliability, recording only four mechanical retirements all year. For the first time in three years, Mika Hakkinen had fewer DNFs than his main championship rival. The McLarens also showed an improvement in all-out race pace. Two years ago, Schumacher and Hakkinen each scored six fastest race laps over the season. This year, the Finn triumphed over the German by a staggering margin of 9-2. It's ironic that this season, rated by many to be Schumacher's finest, is also the only season in which he has scored fewer fastest laps than his teammate - two to Rubens Barrichello's three. Only once before (Canada 1999) had a teammate of Schumacher recorded a fastest race lap. Perhaps Ferrari's claims of 'equal treatment' for Barrichello weren't so far-fetched after all.

The turnaround in expected form also applied to single races and season segments as well. Traditionally, Schumacher suffers from a slow start, an outstanding mid-season stint at his home tracks in Europe, and a weak or error-prone finish as the F1 circus heads east for the season finale. In 2000, he started with a triple, suffered badly during the European leg, and then finished with a perfect quadruple. Normally, you could stake your bottom dollar on Schumacher triumphing at a damp Spa, and likewise for Hakkinen at Suzuka. Again, the 2000 results turned the form-book on its head.

If McLaren have a critical and long-standing weakness against their Ferrari rivals, it is in the wet. Or semi-wet, as Hakkinen has proved to be almost as fast as Schumacher in full wet conditions. Yet, in the sort of greasy conditions where teams and drivers are undecided between dry tyres or wets, the Ferraris reign supreme. Three times (Nurburgring, Hockenheim, Suzuka) Hakkinen lost a race lead to a Ferrari in semi-wet conditions. That weakness, even more than the 16 points lost to disqualifications during the season, ended McLaren's hopes of regaining the Constructors' crown they surrendered to Ferrari last year.

The Schumacher/Hakkinen duopoly cannot last indefinitely, however, and 2000 delivered some clear pointers as to their eventual successors. Jacques Villeneuve spent half of the year walking on water, and the other half out-braking himself. There's no doubt that the Canadian still has immense courage, and an unstoppable will to win. It remains to be seen whether he can keep his head in another tense championship finale.

Pedro de la Rosa also showed precocious talent, although it was difficult to judge his true worth in the iffy Arrows. Nick Heidfeld acquitted himself well in the worst car in the field, even though he and stablemate Jean Alesi occasionally gave the impression that teamwork is a contact sport. Jarno Trulli showed true star qualities, making Heinz-Harald Frentzen look pedestrian at times.

2000's biggest surprise was Williams's young English signing, Jenson Button. Williams have never been the most driver-friendly outfit (ask Alex Zanardi about that), and the team is clearly built around the needs of 'champion in waiting' Ralf Schumacher. Button not only out-qualified his highly-rated and vastly more experienced teammate, he did so at some of the most technical circuits on the calendar - Spa and Suzuka. Button did make some rookie mistakes, like the Monza safety car debacle and a pair of collisions with Jarno Trulli. But generally, he showed maturity and racing smarts well beyond his years. It wouldn't be a surprise in the least if Button also knocks a king-sized dent in Giancarlo Fisichella's reputation next season.

Like any great season, 2000 posed more questions than it answered. During the Benetton years, Michael Schumacher had won championships via loads of fastest laps, but relatively few pole positions. This year, he did it the other way round - nine poles and only two fastest laps. How exactly will he tackle next season? Will the fire still be there, or will the realisation of his dream take that vital few tenths off his performance? And what of Hakkinen? With the McLaren-Mercedes advantage nullified, can the Finn find the motivation to tackle his fourth consecutive championship campaign?

Only one thing seems certain - the World Championship title will go to either Schumacher or Hakkinen again in 2001. Even in the topsy-turvy world of modern F1, any other conclusion is so optimistic it's off the scale.