| ATLAS F1 Volume 6, Issue 40 | |||

|

Glory Beckons | ||

| by Timothy Collings, England | |||

Someone one said that winning a World Championship is winning a permanent place in the history books, but winning one for Ferrari is winning immortality. Michael Schumacher arrives at Japan with the first real chance of achieving just that. And yet, how well do we really know the German star? Timothy Collings writes about the enigmatic Michael Schumacher Someone one said that winning a World Championship is winning a permanent place in the history books, but winning one for Ferrari is winning immortality. Michael Schumacher arrives at Japan with the first real chance of achieving just that. And yet, how well do we really know the German star? Timothy Collings writes about the enigmatic Michael Schumacher

Another victory in his Ferrari on Sunday and he will join the pantheon of the sport's greatest drivers, a club stocked with triple champions like Juan-Manuel Fangio, Alain Prost, Jack Brabham, Jackie Stewart, Niki Lauda, Nelson Piquet and Ayrton Senna.

But the inner man, the Schumacher who grew up as the son of a bricklayer from Kerpen-Mannheim in the flatlands of northern Germany, remains relatively unknown. Few have been allowed close to the 31-year-old, or invited into his inner sanctum, let alone his home overlooking Lac LeMan in Switzerland.

Famous all over the world, he remains one of the most enigmatic of all those drivers whose singular speed has graced the sport. "I think I know him," said his former Ferrari teammate Eddie Irvine. "But I honestly couldn't say I do. In this business there are very few people you want to have knowing what you're really like. It's not in your best interests. If you're playing chess, you don't tell your opponent your next move beforehand, do you?"

In spite of this, no one really knows him in the way that many of the acclaimed are known. He is a working-class hero from humble origins, but not one who has had any need to shout about his feats.

Indeed, his only concession to media and public interest in his 'other' life away from the track is to train and, occasionally, play for his local village soccer team.

He is not by any means the Greta Garbo of the pitlane. But he is a man who has carefully planned, organised and structured his life to ensure that the professional side - his racing and work for Ferrari and the Michael Schumacher image - does not interfere with a private life that is as near to ordinary as possible for someone who reportedly earned more than $100 million last year. His family, he has often said, are most precious and private of all to him.

He is accessible to the media and he can be talkative. But he deflects those questions seeking to penetrate his personal and psychological armoury in a way that Senna, his immediate predecessor as a truly great world champion, would never attempt.

One-Liner

Where Senna embraced talk of philosophy, morals and the meaning of life, Schumacher shrugs and grins. A one-liner is the best a reporter can hope for, unless it is a topic close to his heart and external to his personal life.

He is never photographed, for example, at home and his true friends, from his private life, do not give interviews. He does not discuss his parents' divorce. He is rarely photographed with his own children. Yet he has worked for UNICEF and represents the drivers on safety issues in Formula One.

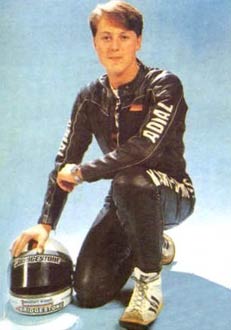

He rose through the ranks of international karting, Formula Ford and German Formula Three, on the way beating Mika Hakkinen in the blue riband Macau F3 'Grand Prix' race, after a controversial collision which left the Finn in the barriers. Schumacher grinned with pleasure at the recollection. "He should not have tried to pass me on the final lap," he said.

His genius for mechanical sympathy was apparent at a tender age as was his ability to instil loyalty and enthusiasm in a team around him. Lacking private funds (unlike Senna, for example) Schumacher needed sponsors to support his career. Men like Jurgen Dilk, who backed his karting, remain loyal and are rewarded. Dilk is the president of Schumacher's hugely-successful fan club in Germany.

Weber, like Schumacher, was clearly a man prepared to bend the rules if it suited him. At Benetton, this willingness to blend so-called professionalism, including on-track 'professional fouls', with his raw speed, shrewd racecraft and astounding car control in the wet, complemented the team's tactical acumen.

With Schumacher as their focus, Benetton collected the drivers' title in 1994 and 1995 and their only constructors' crown in 1995. Schumacher's teammates, however doughty, were also-rans.

Ruthless, but smiling, Schumacher was motor racing's 'baby-faced assassin' and not even the series of controversies that followed him in 1994 upset his concentration, as he collided with championship rival Damon Hill to secure the title in Adelaide. Humility, like humour, was not a natural Schumacher characteristic in his professional life.

This showed with various flashes of the ruthlessness on track long before the European Grand Prix of 1997, when he sullied both his and Ferrari's reputation by colliding deliberately with Canadian Jacques Villeneuve's Williams at Jerez. Schumacher lost everything in that move, including the title, but it revealed the singular win-at-all-costs racer who has always pushed to the limits of his fitness and his speed to succeed.

Since then his ambitions with Ferrari have been thwarted, most notably by a broken leg midway through the 1999 season. The experiences of disappointment, pain, acceptance that another driver, Hakkinen, has taken two successive titles, and an enforced absence from the track, have left the public in expectant mood. This Sunday, he has a chance to deliver himself from the past with a clean victory for Ferrari, one that will wipe clean his reputation and enter him into the company of the triple champions.

"I have come from nothing, with no money," he told James Allen for his book 'The Quest for Redemption'. "It makes me and my parents very happy about what we have achieved. Whether I have handled it well - personally, I think I have. But there will be people who think the opposite..."

|

| Timothy Collings | © 2000 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: comments@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |

The German, winner of the drivers' crown in 1994 and 1995, 42 Grands Prix and more controversy than any other driver around, knows that history beckons.

The German, winner of the drivers' crown in 1994 and 1995, 42 Grands Prix and more controversy than any other driver around, knows that history beckons.

Little is familiar about the private man who makes use of a personal jet to fly home to be with his wife Corinna and two young children, his pets and his 'toys', including an impressive range of cars and motor bikes.

Little is familiar about the private man who makes use of a personal jet to fly home to be with his wife Corinna and two young children, his pets and his 'toys', including an impressive range of cars and motor bikes.

For Schumacher, such pragmatism pervades all areas of his life. From his earliest racing to his last race, the United States Grand Prix in Indianapolis, he has demonstrated an utter willingness to compete to the limit, using every trick in the book and within his understanding of the rules, to maximise his hopes of winning. For him, nothing has come easy, on or off the track.

For Schumacher, such pragmatism pervades all areas of his life. From his earliest racing to his last race, the United States Grand Prix in Indianapolis, he has demonstrated an utter willingness to compete to the limit, using every trick in the book and within his understanding of the rules, to maximise his hopes of winning. For him, nothing has come easy, on or off the track.

It was Weber who guided him through the Mercedes-Benz junior team and into Formula One with Jordan in 1991. Aged only 22, he made his debut at the Belgian Grand Prix. He qualified seventh, broke the clutch at the first corner in the race, but did enough to convince the world he was a spectacular new arrival. At the next race, the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, he was driving for Benetton.

It was Weber who guided him through the Mercedes-Benz junior team and into Formula One with Jordan in 1991. Aged only 22, he made his debut at the Belgian Grand Prix. He qualified seventh, broke the clutch at the first corner in the race, but did enough to convince the world he was a spectacular new arrival. At the next race, the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, he was driving for Benetton.