|

From the Banking to the Barricades: Protest Movements and F1 |

| by Mark Glendenning, Australia | |

|

Part Two: Save the Monza Banking

It's often said that Monaco is the jewel in Formula One's crown. Glamour has long been a part of Formula One, and there's no better place on the championship calendar than the Principality for those who want to compare Rolexes or be photographed with a rock/movie/catwalk star. Having a harbour full of large yachts, an extravagant casino, and a royal family that is quite partial to a few hundred horsepower doesn't hurt Monaco's prestigious reputation either. It is a tiny corner of the world that has become virtually synonymous with the notions of excess, indulgence, and obscene amounts of money - much like Formula One. And while most drivers hate actually driving there, it is a race that every one of them dreams of winning.

True, Monaco has a long tradition of its own - indeed, there are few circuits that have seen more Grand Prix racing than the race through the streets. But it is Monza that offers Formula One the most tangible link between the past and present. The fact that the circuit has seen almost 80 years of racing means that the history books read as a virtual encyclopedia of great drivers, teams, and battles. It has also hosted some of the sport's greatest moments - the closest finish in a Grand Prix, the fastest Grand Prix, the most lead changes in a Grand Prix; as well as some of the darkest. Jochen Rindt, Wolfgang von Trips, and Ronnie Peterson are just some of the drivers who have lost there lives there, and there have also been a large number of spectator fatalities. But even these don't tell the whole story. For that, you need to head across the infield until you encounter the historic banking.

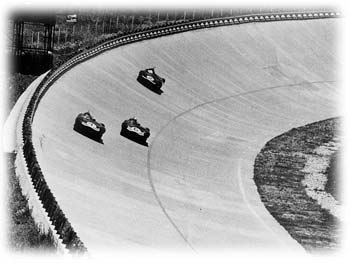

The original circuit configuration included two huge banked corners, although only the South banking was used between 1934 and 1950. The banked sections then lay dormant until 1955 and 1956, when both corners saw action. They then disappeared again, returning to use in 1960 and were finally retired from Formula One for good in 1961. The Mille Chilometri di Monza (1000km of Monza), a race for Sports Cars and GTs, used the banks between 1965 and 1969; several speed record attempts were made there in the mid-70s, and the Rally of Monza visited the banking annually from 1978 onwards. Nobody, though, has been able to agree upon a firm plan for the future of the banking. The announcement that the banked sections were scheduled for demolition, however, attracted condemnation from motorsport enthusiasts worldwide, and led to the birth of a grassroots movement devoted to the preservation of a rare link with motorsport of yesteryear.

The banking has actually been under fire since the late 1980s, when the Monza town council proposed that it be demolished in order to revive an older plan to construct a telescope in the park. The banked sections became further endangered when a technical committee found them to be dangerous to the public in 1993. The final order to remove the banks followed an agreement between the town council and the SIAS (Societa Incremento Automoblismo e Sport) over the future administration of the circuit.

In fact, the plans to demolish the banking are just the tip of the iceberg, for there are calls from certain groups to remove the entire Autodromo Nationale di Monza. Not surprisingly, the majority of the pressure is coming from environmental and political circles. Threats to end the Italian Grand Prix at Monza or close the circuit altogether are nothing new; indeed there have been several attempts in the last ten years alone. The wake of Senna's death in 1994, for example, saw the FIA make a number of demands upon Monza's administrators to modify the circuit in the interests of improving driver safety.

The required modifications to the circuit necessitated the removal of 300 trees. There was an instant outcry from the Lombardy Government (the Monza's regional government), the Italian Greens, and a coalition of local environmental organizations. Local businesses and the town council, however, supported the modifications. The subsequent stalemate led to a very real possibility of the 1994 Italian Grand Prix being cancelled, however the race was eventually rescued when a compromise was reached whereby only twenty-four trees were lost. Hostilities resumed in 1995, though, when further plans for modifying the circuit included the removal of 185 trees. Again, the race went ahead after an eleventh-hour agreement saw 115 trees relocated, and none destroyed.

You might, at this point, be wondering why those responsible for the circuit's layout don't pay greater attention to the environmental issues when they know that any plans that involve the mass felling of trees will bring trouble and slow the entire process down unnecessarily; particularly when the eventual compromises that are reached indicate that trees do not usually need to be removed on the scale that are initially suggested. It would be expected that a 'close-to-ideal' plan that could proceed without any problems would be preferable to an 'ideal' plan that causes no end of trouble, almost leads to the cancellation of the race, and invariably winds up being changed anyway; but I guess if I knew the answers I'd be making a fortune as a circuit designer.

The view of the greens, or 'I verdi', is more as less as one would expect. Their primary concern is for the welfare of the remnants of the Bosco Bello (Beautiful Wood), a forest located within the Monza Park precinct that dates back several centuries. It is apparently these older trees that have borne the brunt of the circuit modifications over the years. The greens have employed a number of strategies to disrupt the redevelopment of the circuit, however the most effective has been through the legal system; where a series of injunctions and court orders have succeeded in slowing down construction work on the track on a number of occasions.

The political situation was, as always, a little more complicated. At the head of the political push to demolish the circuit are the Lega Nord, or Northern League. Some time ago, the Lega Nord held seats in the region of Lombardy. During this period, the party was an ardent supporter of the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, for it was appreciative of the global spotlight recognition that followed the Grand Prix into the region each year. The party was later voted out, and has since had a dramatic change of heart about the race. Once the pride of the region, Monza's Italian Grand Prix was now considered to be symbolic of the 'corrupt and totalitarian' Italian government; thus, the Autodrome was now regarded with the appropriate measure of contempt.

For the most part, the Monza residents themselves seem quite keen to keep the race where it is. To an extent this support would be commercially based, for there can be little doubt that the Grand Prix represents a significant injection into the local economy each year. It would a surprise if there was not a substantial amount of pride in there too though. To live in a town that hosts a Grand Prix is exciting enough, never mind one with the history of Monza. But if you're Italian, and you live within a stone's throw of Ferrari's home circuit, then that is something else altogether. It is ironic then, that if the demolition of the banking is to go ahead, it is the people of Monza who would be expected to meet the costs - a bill which has been estimated to top two million dollars.

So what's being done to save the banking? Most of the Formula One magazines ran some sort of news item when the announcement that the banking was under threat was made in 1998, but the weight of actually taking the fight to the authorities has fallen largely on the shoulders of Englishman Chris Balfe. Within days of hearing about the demolition plans, Balfe launched his 'Save the Monza Banking' campaign, a movement that is centered around a purpose-built website.

Besides providing news and updates about the status of the banking to racing fans, Balfe's site also contained a petition to save the banking. The petition was a remarkable success, attracting around 1500 signatures from almost seventy countries. Amongst the names were some of the most revered in the history of the sport, including such luminaries as Sir Stirling Moss, Sir Jack Brabham, Phil Hill, Jody Scheckter, John Surtees, and John Watson. John Frankenheimer, director of the film 'Grand Prix' (which used the banking for some scenes) also lent his support. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Balfe's calls to modern Formula One personnel went largely unanswered - of all that were contacted, only Jos Verstappen, Goodyear, and Tyrrell responded. None of whom, coincidently, are involved with the sport anymore (though Verstappen always seems to be lurking around the fringes somewhere). Elsewhere, the site also contains quotes from Jacques Villeneuve and Jean Alesi supporting the push to save the banking.

The petition was presented to Monza mayor Roberto Colombo in September 1998. Colombo welcomed the petition and announced his intention to support the cause, saying that he would attempt to persuade the town council to reconsider their position. A particular strength of the campaign is that it has not only successfully communicated the feelings of racing fans worldwide, but it has also created a proposal for a way in which the banking could be used in future. Balfe's idea is to use the banks as a centerpiece for a relocated motoring museum, which would be shifted to the site from Arese. The suggestion attracted the support of the president of the Regional Council, the head of Milan's engineering college, and the president of the Alfa Romeo racing team. The local press also backed the idea.

So where do things stand now? As is often the case when dealing with Italian bureaucracy, it's hard to say. For a long time it seemed that Balfe had won his fight, having been advised by the SIAS that the banking was no longer under threat. As recently as October, however, it seemed that the tide was turning once again, following an intensification of effort from the greens. There has been little word on the situation since.

It is impossible to imagine Formula One without Monza - it is a circuit that, more than any other, represents the tradition and passion that is at the heart of F1. In a sport that faces constant accusations of becoming cold, commercial, and impersonal - heartless, in other words - Formula One needs Monza the way yaks need mountains. What is the FIA's stance on the whole thing? Who knows? And even if they do support the retention of the banking (and indeed of the whole circuit), does Bernie's power stretch far enough to influence the Italian government? I'd personally be surprised to see the circuit disappear, but then again, this is Italy. Time will tell.

* Some of the information contained here was based upon the contents of the Save the Monza Banking website. The site can be found at http://wkweb5.cableinet.co.uk/ferrari/monza_camp.htm

|

| Mark Glendenning | © 2000 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: glendenning@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |