|

Atlas F1 Exclusive Bernie Ecclestone: The Interview |

| by Thomas O'Keefe, U.S.A | |

|

He says the idea to float F1 was not initiated by him but rather by the teams - primarily Ferrari

"Bernie Ecclestone: The Interview" all began with an extensive and critical profile of Bernie Ecclestone, called Formula Bernie (Tobacco + TV + Tracks = $2 Billion), published late last year at Atlas F1 and written by me, an American lawyer and Formula One journalist, who practices law in those two well-known hotbeds of Formula One activity, New York City and the U.S. Virgin Islands. I sent Bernie the article, which had been based upon what was available on the public written records, and requested a face-to-face interview to explore with him Y2K Formula One issues.

Bernie agreed to meet just after the New Year in his office in London and when we met we talked for an hour and twenty minutes: no ground rules were set, no time limits; no flaks, no intermediaries, no requirement that questions be submitted in advance.

When I arrived at the appointed hour and place, other than a tastefully understated modernistic office in a posh setting in London just off Hyde Park, there were few indicia of the trappings of wealth and power one might associate with Formula One's legendary impresario supremo and someone recently named Britain's richest person, now reportedly worth 2.4 billion pounds, just nudging Queen Elizabeth at a paltry 2.0 billion out of first place. No coterie of hangers on, gatekeepers, handlers and aides-de-camp were in evidence; just a pleasant and efficient receptionist who offered me tea and a guy out front washing down Bernie's Audi station wagon.

Instead of the dictatorial and calculating character I had heard (and written) about and expected to meet, what I found was a modest and unassuming man caught up in the frenetic pace of his business day, working as hard as if he was still earning his first dollar, passionate about perfection and about not wasting time, fully alert to all the goings on about him and able to flit in conversation seamlessly from what happened yesterday to what happened 50 years ago with wit and intelligence and an awesome command of his subject.

Did Bernie have a specific reason for granting me this audience the editors asked me? Was it because I was a lawyer who had written on the European Commission antitrust proceedings involving Formula One? Was it perhaps because I was an American Formula One fan, a still-uncommon breed, that Bernie invited me in to practice his Charm Offensive before taking it on the road to America? Or was it because I was a critic he couldn't resist tweaking? Or did he just like my "Formula Bernie" articles? (My preferred explanation, of course.)

As it turned out, he had read "Formula Bernie" and - perfectionist that he is - had a few corrections to discuss with me, in the manner of a stern schoolteacher. Luckily for me, however, by the time of our interview he had forgotten most of his objections, so, as he put it, "it's your agenda," which follows, in my words and in his.

In 1997, Sylvester Stallone announced that he had acquired the rights to do a film about Formula One after negotiating face-to-face with Bernie. Unfortunately, notwithstanding the best intentions of these two Titans in their own fields, there will be no film for us long-suffering F1 fans to look forward to. Unless something dramatic happens, it looks like we could all go to our graves watching re-runs of John Frankenheimer's 1967 racing movie classic "Grand Prix".

But, as Ecclestone emphasizes, the people from Hollywood seemed not to understand that they had not purchased the rights "to film a book" but had signed up to operate within the dynamic environment of the Formula One world, where, unusually, Hollywood would have to subordinate itself and take a Back Seat to the existing welter of hundreds of contractual commitments Formula One already has in place with sponsors, promoters, constructors and television producers that criss-cross but intersect on the grid of every Formula One race. Hollywood apparently had difficulties coming to grips with not being in the Driver's Seat.

Bernie does not pretend to know the movie business but has probably had more real life experience than most in making Formula One films, having worked with Al Pacino and Sydney Pollack on "Bobby Deerfield" and with John Frankenheimer and James Garner on "Grand Prix". Jochen Rindt, who Bernie managed at the time, was one of the drivers featured in "Grand Prix" and Bernie is intimately aware of the ups and downs of making that film. Indeed, Bernie says that when he looks at the film now he is amazed at the quality of Frankenheimer's "Grand Prix" since he knows the chaotic circumstances under which it was filmed, with limited budgets and mocked-up Formula Junior cars masquerading for the real thing. Bernie also points out that most filming was not done during actual races or race weekends, apparently one of the sore points with Sly's film lawyers and producers.

James Garner was recently quoted on the daunting logistical problems that faced Frankenheimer back then in trying to shoot around the Formula One world as it is, and he went about their respective businesses:

"We were five weeks at Monte Carlo [which produced the opening portion of the film with John Surtees and his Ferrari leading the pack in the opening laps and James Garner's BRM being launched into Monaco's harbor after crashing with his teammate], then two weeks at Spa [which was ultimately run in a horrific thunderstorm on race day, producing a spectacular series of accidents that were incorporated into the film], five weeks at Brands Hatch [where the real Ferraris chose not to run that year but had to be cobbled together from older Brabhams and Lotuses painted red to 'win' the British Grand Prix], about 10 days at Zandvoort [which captured on film forever the atmospheric Dutch seaside track no longer used in Formula One that runs amongst grass and sand dunes and is located a stone's throw from the North Sea], five weeks at Clermont-Ferrand [when the actual French Grand Prix that year was at Reims and which produced more of an arty dream-like sequence in the movie rather than a race], five weeks at Monza [which produced the spectacular marquee shots taken on the bumpy and dangerous Monza banking to which Frankenheimer was given special access]."

In all, "Grand Prix" took six months to make, a remarkable achievement that Bernie thinks turned out well, all things considered.

And now, given the lapse of time, a further problem has emerged: whatever "rights" were embodied in the "bit of paper" signed for Sly by Bernie at Monza have now expired. To make matters worse, Bernie says that the new financial people coming into Formula One, i.e., the investment banker types and their clients, the team owners and manufacturers, apparently believe Bernie's original terms with Sly were too generous to Sly and did not fairly reflect the true value of turning over the F1 franchise to Sly for his film. None the less, Bernie repeats his hope that "the film doesn't die" and hopes he and Sly would be meeting in the States soon for one last showdown.

For Sly's part, he announced after my interview with Bernie that he has given up on the Formula One movie and that he will instead convert his Formula One script to a movie called "Champs," about Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART), the American Indy car series.

Says Stallone: "I worked hard for two or three years in F1, but there's a certain individual who runs that sport that has his own agenda and made it impossible to do a movie . . . I thought we had a deal and every time I went to sign, Bernie would raise the price. It's all about money to him."

Putting the best face on a sad outcome Sly made a virtue of necessity. "CART is much more of a family atmosphere and the people are eager to do this project. Actually, this is a disaster that turned out in my favor. So thank you, Bernie; now take the hatchet out of my back." Well I guess that frees up another Pit Pass at the Grands Prix this season!

Why was Indianapolis, Indiana chosen as the permanent home for the U.S. Grand Prix over other potential venues Formula One racing fans might more instinctively favor such as Watkins Glen, Elkhart Lake, Laguna Seca, Long Beach or Las Vegas? "Indy is Indy," Replies Bernie. "When you go anywhere in the world, and you talk about Indianapolis, it is like talking about Coca-Cola or Rolls-Royce: everybody knows it . . . and we need to have that kind of place that our people [i.e. the sponsors] can bring their guests to." Picturesque road circuits set amongst trees in obscure parts of Wisconsin and upstate New York need not apply.

When we turn to a discussion of projected attendance figures for the Indianapolis Formula One race, Bernie reverts to the flinty-eyed number-crunching promoter in him that, as you might imagine, lies not too far beneath the surface. He seemed skeptical when told that the Indianapolis Motor Speedway is thought to have in the range of 350,000 to 375,000 paying ticket holders at each Indy 500, even during the Indy Racing League era. (A reported 375,000 people attended the 1999 Indy 500.)

Only back in the late 1930's in the heyday of the Old Nurburgring when the rear-engined Auto Unions faced off against the Mercedes-Benz team has Formula One ever approached attendance figures in the 350,000 range. Most Formula One races draw no more than 120,000 or so and many attract even fewer fans, although the ticket prices in Formula One are higher, thus providing higher profits for the promoter.

As if grasping for analogies as precedent for "first-time" events, Bernie recalls off the top of his head that the first Hungarian Grand Prix in 1986 had probably 160,000 in attendance (the official figures say 200,000). Although Bernie says he "does not know how many seats there are" at Indy, he seems conscious of the disparity between the numbers Indy typically attracts and the lower attendance figures at Formula One races, but he feels that Formula One is in good hands and that Tony George and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway "will look after us."

(Tony George himself is playing the "lowering expectations" game and has been quoted as hoping that 200,000 people show up for the Formula One race in its first year.)

For how long will the U.S. Grand Prix race be based at Indy? "I am sure as long as Tony George is alive and I am alive it is settled [as a permanent site.]" says Bernie. "And I am thinking of staying on a long time, although if my wife were to hear that she would not be at all happy but that's the way it is."

All this talk of attendance figures at Indianapolis leads to a digression over open wheel motorsport races at Long Beach, a venue that uniquely has had both Formula One cars as the U.S. Grand Prix West from 1976 through 1983 and subsequently the Indy cars, both types of races run under the tutelage of promoter Chris Pook.

Bernie and Pook have apparently had a friendly disagreement over who did what for whom when it comes to Long Beach, with Bernie arguing that Formula One in effect "made" the Long Beach venue and that despite the fact that Formula One ticket prices where higher, ticket sales dropped off after Formula One left in 1983. For his side of things, Chris Pook claims that he tried unsuccessfully to get Bernie to reduce his race fee and was forced to shut down Formula One at Long Beach in 1983 when Bernie refused to go along. It sounds like Bernie and Pook were a fair match. Says Pook: "You can't let him get ahead of you in negotiations . . . Once he does, you never catch up."

Speaking of attendance figures, has Bernie himself ever attended the Indy 500 or seen the newly-built Formula One track at Indianapolis tucked inside the infield of the famous 2.5 mile banked oval track? Interestingly, it turns out that Bernie has been to the 500 two or three times back in the 1970's and 1980's and believes that the event lives up to its self-proclaimed description as the "Greatest Spectacle in Racing." But he sheepishly, if candidly, admits that he doesn't recall actually sitting still for all three hours plus and 200 laps of any particular race "I used to last about twenty minutes, half hour!" he admits. Take no offense Tony George: you get the feeling that half an hour is about the limit of Bernie's attention span generally.

Is Bernie at all concerned about the 1909-vintage infamous low walls and catch fencing on the banked oval portion of the track and the absence of the runoff areas and gravel pits we associate with modern Formula One circuits? "The part we are going to use, we won't be subjected to [the centrifugal forces of a banked track] . . . it is not the banking as such . . . we will not be using that much of it, just the top of it," He replies. We shall see if the drivers have the same reaction as Bernie to this unique hybrid of a track, part banked oval, part straightaway, part road circuit.

Interestingly, of all the 22 Formula One drivers, only Jacques Villeneuve actually has raced at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway when he participated in the 1994 and 1995 Indy 500's, coming away the winner in 1995, before moving on to Formula One in 1996. But even Villeneuve doesn't have that much of an advantage since the Formula One track will run clockwise around the Speedway while the Indy 500 runs the other way around. Bernie also confirmed that Canadian-by-way-of-Monaco Jacques Villeneuve is as close to an American driver as will participate in the U.S. Grand Prix: there won't be any local "ringers" added by the teams to give the fans a local hero to cheer for as had been the practice years ago in Formula One.

But now that the Formula One track in the infield is built, will the US fans come? Bernie notes by way of precedent, that when Tony George first allowed the Speedway to host a NASCAR event in 1994, the Brickyard 400, Tony had the same concern as to whether people would come to Indy to see the stock cars and, if so, which people would come, Indy regulars or new people. Since the Brickyard 400 has been a smashing success since its inception (as an example, 320,000 people attended the 1999 race), those concerns about whether the magnetism of Indianapolis is transferable have been laid to rest and Tony George believes Formula One will also be embraced by the people who love to come to Indianapolis to watch racing and watch themselves, supplemented of course by the usual hard-core Formula One fans who already follow the races worldwide on television and will now have the chance to come to see a race on American soil.

Since rumors of Bernie's retirement seem greatly exaggerated and have been flatly denied by the man himself, what is all this talk that Formula One is for sale and that Bernie is getting out while the getting is good, by taking Formula One public on the London Stock Exchange? According to Bernie, this whole floatation of stock plan was not initialed by him but is the result of his co-partners in Formula One - the Team Owners, Ferrari prominently mentioned - constantly asking the following fundamental question: "the teams want to know, what happens if Bernie dies . . . or" - Bernie says wistfully with a glint in his eye - "runs away." Does Bernie mean the manufacturers? "No, I mean the teams," he says, and immediately adds: "like Ferrari."

So now that an Initial Public Offering ("IPO") has been decided on as the way to go, why hasn't it happened? And is the antitrust investigation commenced by the European Commission which charges that the contracts negotiated by Bernie and the FIA that control TV broadcast rights to Formula One violate the antitrust laws the reason for the holdup of the IPO, either legally or as a practical matter.

Bernie's answer is twofold (as it often is): first, the European Commission does not have formal regulatory approval over the IPO and Formula One could go out and float its stock tomorrow if it so wished. Except, he says, the forces of darkness in the City and on Wall Street that value stock have a way of discounting value when a Sword of Damocles like the European Commission investigation is hanging over a company that wants to go public: that's the reality of things. So if Formula One were to launch the IPO when the capital markets were still concerned about the outcome of the European Commission proceeding, Formula One could end up selling itself too cheap. Obviously, it's not Bernie's way.

Furthermore, according to Bernie, the European Commission - at least the current staff - have educated themselves about the FIA and the business of Formula One and he hopes that they are coming around to understanding that antitrust laws which are intended to protect against monopolies abusing their power to keep smaller competitors out of their market are simply not applicable to a sport like Formula One which is not a "market" within the meaning of traditional antitrust law.

"They say Formula One is a market which it can't be, obviously," Bernie says. "Our market is independent, it's a sport." Bernie is confident that once the European Commission absorbs the complexity of Formula One, the matter will be resolved to everyone's satisfaction. "They're getting to grips with it ," he adds, "and we're getting it sorted out."

How long it will take to sort things out is a matter of conjecture. Bernie projects that the proceeding will be over by the end of the 2000 Formula One season. According to sources close to the European Commission proceedings, however, the matter has only recently been fully briefed before the Commission and now that the issue has been formally joined, the Commission's schedule in Brussels and that of the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg take over. With trials and appeals ahead, the matter could drag on like the case of Jarndyce v. Jarndyce in the Dickens novel "Bleak House" - for 5 years or even more, not a time frame calculated to mollify those team owners and their bankers and financial advisors who are seeking certainty and stability in Formula One's financial structure.

If Bernie's prognosis is correct, the European Commission obstacle will melt away and the IPO can go out at full value within a year from now. But if the 'Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce' mode sets in, the investment bankers will be back to their calculators as to a valuation of Formula One. In a perverse and bizarre sort of way, if the 5 year trials and appeals scenario holds sway, then investors in Formula One will at least have the comfort and certainty in the medium term that the current prosperity of Formula One will continue unabated and unhampered by the regulators while the European Commission proceeding is pending.

As things stand, Bernie believes that the focus of the European Union should be to protect Europe but his view is that its policies and decisions seem to favor America and Asia to the disadvantage of Europe. The net effect: "they are getting rid of the entrepreneur," says Bernie, and making it difficult for Europeans to run their businesses in a competitive way vis-a-vis the rest of the world.

Why is it that there seems to be a qualitative diminution in the caliber of TV coverage that goes out from each Formula One race as the 'world feed', and what is the likelihood that better coverage will trickle down from the Bernie Digital Pay TV operation to those of us in the Great Unwashed who rely on the world feed?

First of all, digital TV will continue to be available only in what Bernie calls the Benelux countries (Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg) along with Germany, Italy and parts of France, still not in England until a contract is signed and not in the United States because of technical problems relating to digital capability.

So the next time we are following Jean Alesi's in-car and he goes out and there is no other in-car footage, complain to your world feed producer, not to Bernie, and tell them Bernie said so!

Since I notice that there is no computer or other electronic paraphernalia in sight on his elegant black desk, I take it that Bernie has yet to discover the joys of cyberspace and particularly the explosion of Formula One sites on the Web.

The new site will not be a revamping of the current FIA site but another one entirely. Bernie remains perplexed, however, about the proliferation of Formula One in the Web, fretting again on his constant preoccupation, the March of Time: "I don't know how people find the time to go to all these sites . . .there are millions of them," he says.

"I was never at war with Jean-Marie Balestre," Bernie acclaims, contrary to what is popularly thought. The so-called FISA/FOCA war was simply about the turbo faction (Ferrari and Balestre) vs. the impecunious non-turbos faction (Bernie and the English teams). After negotiations that took place elsewhere, a press conference was held in Maranello "to sign the bloody thing for PR purposes," as Bernie names it, with Enzo Ferrari presiding at the announcement by Bernie and Balestre, that ultimately led to the March 1981 Concorde Agreement, the single most important document that has shaped modern Formula One.

Bernie gets a respectful and far-away look in his eye when he talks about the Commendatore and his trips to Maranello: "you know, he never traveled and he never went to the races, only to practice;" nevertheless, "up until the time he died he knew what was going on in Formula One and at Ferrari." Bernie says he used to "brief [Enzo Ferrari] three or four times a year" on issues in Formula One, and, according to Bernie, "Ferrari was very supportive of me," as Bernie evolved from team owner to the chief impresario of Formula One. You get the feeling that he genuinely misses the Old Man and is bemused that he, Bernie, has somehow become the focal point of Formula One as the Commendatore once was in earlier times.

In the American Indy Car series, there have been notable women competitors like Janet Guthrie in the late 1970's and Lyn St. James in the 1990's and in the Year 2000, sprint car ace Sarah Fisher, all of 19 years old, will become a full-time driver in the Indy Racing League.

Formula One has not been as hospitable to women: the only woman to finish in the points was Lella Lombardi in 1975 who scored 1/2 of a point in a rain-shortened Spanish Grand Prix race full of accidents; more recently, a few women have been given chances to qualify a Formula One car but have been snake-bitten by having only lesser equipment available to them. While there are many women on the various Formula One teams in various support capacities, to date no women drivers. In recent memory, the most striking involvement of a woman in Formula One is the recent appearance of Supermodel Naomi Campbell on the arm of Supertec's Flavio Briatore at many Grands Prix! What does Bernie, father of two teen-age girls himself, think of the prospects for a woman driver in Formula One?

Bernie's views at first blush were disappointedly provincial and traditional but characteristically direct: "in all likelihood they will never get the opportunity because no one will ever take them seriously [or sponsor them financially] . . . therefore they're never ever going to get into a competitive race car." And besides, says Bernie, "where will they come from" since there is no existing pool of woman drivers to choose from?

When asked hypothetically, what if Oprah Winfrey, one of the world's wealthiest woman, ponied up the money to back a woman driver so that sponsorship was not the issue, what then? Still no dice: "Whoever she's got, it wouldn't make any difference . . . who is going to take a chance? Ferrari can't take a chance."

But, unfortunately, he is not expecting that welcomed multicultural sight to emerge on the grid at Monaco anytime soon. Time will tell of course but on this point, I somehow suspect Bernie will be proved wrong and that the legacy of former Formula One drivers Maria Theresa de Filippis and Lella Lombardi will be taken up sooner than he expects by some teenage girl like a Sarah Fisher who is now somewhere in Europe, America or Brazil, learning how to drive a go-kart under her father's tutelage.

|

||||

|

Bernie and Deaths in the Family

To this day, the names of Jochen Rindt and Stuart Lewis-Evans, both drivers that Bernie managed when they were killed in race cars, come to his lips quite easily and it turns out that Bernie was also close to Ayrton Senna and his family and still mourns that loss. When asked how one deals with such tragedies, Bernie turns stone-faced toward the window and is for the only time in our interview uncharacteristically mute.

Epilogue

I consider this encounter to be Bernie's interview with the Common Man and I think he treated it that way too, since I am by no means a renowned professional Formula One commentator or otherwise associated with any teams or sponsors of Formula One. I went in somewhat of a skeptic but came away convinced that Formula One is in good hands and that Bernie intends to stay as the head of Formula One at least through the conclusion of the IPO and European Commission proceedings - which is probably years away - and hopefully longer. I recognize that Bernie-bashing is almost as universal in Formula One circles as (Michael) Schumacher bashing and Bernie seems like he could care less about it: he seems reconciled to being the lightning rod for all that is wrong with Formula One. But though Bernie-bashing may make good newsprint and lively Bulletin Board, in Bernie's case, all things considered, I think it is difficult to make the case that is so often proffered that Bernie is Bad for Formula One. Based upon what I have seen of the other possible rivals to his power, we will likely rue the day when Bernie does pass the baton to other people or institutions. He strikes me as the type of man about whom it can be said that God broke the mold when he made him. We can only hope that Max Mosley's prediction will prove to be correct and that the 69 year-old Bernie will be with us in Formula One at least as long as was 90 year-old Enzo Ferrari.

|

The "Business" Of Grand Prix Racing

The Ecclestone Era

Reflections on a Monopoly

Pick 'n' Pay: a Viewer's Guide to Digital F1 TV

Bernie's Midas Touch Goes up in Smoke

Formula Bernie - Part I

Formula Bernie - Part II

Formula Bernie - Part III

Formula Bernie - Part IV |

|||

| Thomas O'Keefe | © 2000 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: okeefe@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |

What went wrong? According to Bernie, it all started well enough at Monza in 1997 with Bernie signing "a bit of paper," as he calls it, that Sly said he needed for the folks back in Hollywood, but then reality set in: people in the business have told Bernie that it was "film lawyers" and producers who bollixed up the plans he and Sly had for the film. Today Bernie recognizes that, "Sly has had to move on" but still "hopes the project doesn't die" and has "no problem with Sly . . . absolutely zero problem with Sly." Indeed, Bernie was emphatic that "if we didn't have the lawyers and we had Sly as the producer we could be filming by summer." Bernie claims to have bent over backwards to support the film project: "Sly knew that we couldn't be any more helpful than we were as far as production is concerned . . . he had access to everything we had (including the Digital TV production footage)."

What went wrong? According to Bernie, it all started well enough at Monza in 1997 with Bernie signing "a bit of paper," as he calls it, that Sly said he needed for the folks back in Hollywood, but then reality set in: people in the business have told Bernie that it was "film lawyers" and producers who bollixed up the plans he and Sly had for the film. Today Bernie recognizes that, "Sly has had to move on" but still "hopes the project doesn't die" and has "no problem with Sly . . . absolutely zero problem with Sly." Indeed, Bernie was emphatic that "if we didn't have the lawyers and we had Sly as the producer we could be filming by summer." Bernie claims to have bent over backwards to support the film project: "Sly knew that we couldn't be any more helpful than we were as far as production is concerned . . . he had access to everything we had (including the Digital TV production footage)."

"Grand Prix" is not renowned for its script but apparently script issues have presented their share of problems in negotiating the ground rules for the Stallone film. Sly was quoted at the Hungaroring in August 1999 saying that there were "a few script issues with Bernie" but that "the script keeps getting better and better" based upon the actual 1999 Formula One season as it unfolded. Bernie confirms that, consistent with his contractual commitments to others, he did have the rights to approve the script to assure that the final result did not disparage Formula One. Giving an example of what he was worried about, Bernie says that "we did not want them having [a story line with] somebody on the Ferrari team running drugs."

"Grand Prix" is not renowned for its script but apparently script issues have presented their share of problems in negotiating the ground rules for the Stallone film. Sly was quoted at the Hungaroring in August 1999 saying that there were "a few script issues with Bernie" but that "the script keeps getting better and better" based upon the actual 1999 Formula One season as it unfolded. Bernie confirms that, consistent with his contractual commitments to others, he did have the rights to approve the script to assure that the final result did not disparage Formula One. Giving an example of what he was worried about, Bernie says that "we did not want them having [a story line with] somebody on the Ferrari team running drugs."

But what about Las Vegas, then, surely an entertainment Mecca? "I was disappointed that we didn't get the job done there," Bernie replies, surprisingly, and adds that he was very interested in running Formula One cars in Las Vegas and not, mind you, through pylons on a makeshift track in the parking lot of Caesar's Palace. "What I had in mind is [the race] running by the Bellagio [Hotel]." Bernie's idea was to Go Big and Flaunt It, but the casinos apparently would not go along; his Formula One circuit would have incorporated the actual Las Vegas Strip running past the major hotels as the main straightaway, a Mulsanne straight in the desert!

But what about Las Vegas, then, surely an entertainment Mecca? "I was disappointed that we didn't get the job done there," Bernie replies, surprisingly, and adds that he was very interested in running Formula One cars in Las Vegas and not, mind you, through pylons on a makeshift track in the parking lot of Caesar's Palace. "What I had in mind is [the race] running by the Bellagio [Hotel]." Bernie's idea was to Go Big and Flaunt It, but the casinos apparently would not go along; his Formula One circuit would have incorporated the actual Las Vegas Strip running past the major hotels as the main straightaway, a Mulsanne straight in the desert!

Bernie has not been involved in the Indianapolis Formula One track construction process but says he is "going there shortly" to see the new track in the flesh. From what he has seen of the track design which connects the twisty bits from the new infield portion to Indy Turns 1 and 2 and Indy's main straightaway, he likes the look of the track and thinks they have done "a super job".

Bernie has not been involved in the Indianapolis Formula One track construction process but says he is "going there shortly" to see the new track in the flesh. From what he has seen of the track design which connects the twisty bits from the new infield portion to Indy Turns 1 and 2 and Indy's main straightaway, he likes the look of the track and thinks they have done "a super job".

Although Bernie says, perhaps (and only perhaps) in a jocular vein that he intends to stay "forever", taking Formula One public is the mechanism chosen by the investment bankers increasingly populating the pit lane for regularizing the organization and valuation of Formula One. (By the way, Bernie says most of these investment bankers working on Formula One financial matters are motor racing buffs so we shouldn't think it is all bankers and lawyers in pin stripes who don't know or care about the sport that are determining the shape of things to come.)

Although Bernie says, perhaps (and only perhaps) in a jocular vein that he intends to stay "forever", taking Formula One public is the mechanism chosen by the investment bankers increasingly populating the pit lane for regularizing the organization and valuation of Formula One. (By the way, Bernie says most of these investment bankers working on Formula One financial matters are motor racing buffs so we shouldn't think it is all bankers and lawyers in pin stripes who don't know or care about the sport that are determining the shape of things to come.)

When Bernie is asked whether the phenomenon of antitrust proceedings being brought in America against Microsoft and in Europe against Formula One indicates that the trust busters in all places are going far afield from the railroad barons and oil cartels that were their traditional targets, Bernie's answer is not antagonistic but the calm resignation of an international businessman based in Europe who has made deals worldwide: "My answer has nothing to do with Formula One. What I think has happened in Europe is that business in general has moved on . . . and these European Treaties have not moved on. It's a worldwide phenomenon . . . people doing business with everyone . . . What we need now is a Treaty of the World not a Treaty of Rome [which originally created the European Union]."

When Bernie is asked whether the phenomenon of antitrust proceedings being brought in America against Microsoft and in Europe against Formula One indicates that the trust busters in all places are going far afield from the railroad barons and oil cartels that were their traditional targets, Bernie's answer is not antagonistic but the calm resignation of an international businessman based in Europe who has made deals worldwide: "My answer has nothing to do with Formula One. What I think has happened in Europe is that business in general has moved on . . . and these European Treaties have not moved on. It's a worldwide phenomenon . . . people doing business with everyone . . . What we need now is a Treaty of the World not a Treaty of Rome [which originally created the European Union]."

Second, Bernie refuses to take the heat from fans as to the lack of in-car cameras. Bernie wants you to know that those 6 in-car cameras made available to the Digital TV subscribers cost $10 -12 million per year and there has to be some differentiation between the world feed and Pay-TV customers for obvious reasons. But Bernie says that the blame for the apparently crimping down on in-car coverage cannot be laid at his doorstep: "the world feed producers have the right to use up to three in-car cameras . . . it is entirely up to the broadcaster . . . they get the choice . . . they can have the three cameras for the whole race if they want to."

Second, Bernie refuses to take the heat from fans as to the lack of in-car cameras. Bernie wants you to know that those 6 in-car cameras made available to the Digital TV subscribers cost $10 -12 million per year and there has to be some differentiation between the world feed and Pay-TV customers for obvious reasons. But Bernie says that the blame for the apparently crimping down on in-car coverage cannot be laid at his doorstep: "the world feed producers have the right to use up to three in-car cameras . . . it is entirely up to the broadcaster . . . they get the choice . . . they can have the three cameras for the whole race if they want to."

I ask him about it and he replies: "We are going to start whatever they call it [a Web site], a proper one, and on that web site I mean we will have things no one else has. We have been working on it for a year."

I ask him about it and he replies: "We are going to start whatever they call it [a Web site], a proper one, and on that web site I mean we will have things no one else has. We have been working on it for a year."

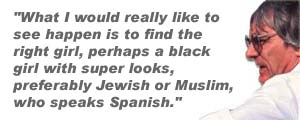

But then Bernie got to thinking about it and began warming to the theme, theorizing about the road a woman driver would have to travel to make it in Formula One, probably coming up through the ranks of Formula 3000. "She would have to be a woman who was blowing away the boys," he says, and, as he thought about it he finally settled on his perfect woman Formula One driver, obviously conjuring up in his mind a woman who looked like Naomi Campbell and drove like Michael Schumacher: "What I would really like to see happen is to find the right girl, perhaps a black girl with super looks, preferably Jewish or Muslim, who speaks Spanish."

But then Bernie got to thinking about it and began warming to the theme, theorizing about the road a woman driver would have to travel to make it in Formula One, probably coming up through the ranks of Formula 3000. "She would have to be a woman who was blowing away the boys," he says, and, as he thought about it he finally settled on his perfect woman Formula One driver, obviously conjuring up in his mind a woman who looked like Naomi Campbell and drove like Michael Schumacher: "What I would really like to see happen is to find the right girl, perhaps a black girl with super looks, preferably Jewish or Muslim, who speaks Spanish."