For the regulatory body of any sport, there is a fine line between accommodating technological innovation and preserving the 'purity' of that particular sporting code. For the FIA, that boundary is demarcated by traction control.

Tolerated up until the end of 1993, traction control was subsequently declared illegal from 1994. The FIA's rationale for banning traction control was simple: limiting wheelspin should be a driver skill governed by judicious throttle control, not by an electronic driver aid.

Tolerated up until the end of 1993, traction control was subsequently declared illegal from 1994. The FIA's rationale for banning traction control was simple: limiting wheelspin should be a driver skill governed by judicious throttle control, not by an electronic driver aid.

Now, in an abrupt about-face, the FIA seems once again willing to tolerate traction control and, provided the teams agree, traction control systems could be reintroduced early in the 2001 season. It's a proposal which has already ignited controversy and emotional debate, from drivers, fans, and engineers alike. While it may seem a uniquely F1-based dilemma, the traction control issue has obvious parallels in other sporting codes.

One example is tennis. During the 1960s heyday of Rod Laver and John Newcombe, wooden racquets were the only choice. Prone to cracking, and with a fist-sized sweet-spot, it took great skill to wield such an unforgiving tool effectively. The subsequent generation of Ashe, Connors, Borg and McEnroe brought the introduction of oversized and oddly-shaped racquets made from metal or graphite. Touted as being 'unbreakable' (although McEnroe quickly dispelled that notion), these monstrosities were despised by tennis purists. With a sweet-spot several times as large as traditional wooden racquets, these new-fangled devices would surely eliminate much of the sport's skill factor...

Golf has also seen pitched battles between purism and technological advancement. The grand old courses like St. Andrew's and Augusta were designed to provide a stern test for players armed with cane-shafted clubs and 'feathery' balls. Over the decades, golf ball design was refined to produce balls which fly further, straighter and spin faster than the featheries of yore. Clubs were enhanced firstly with steel shafts, then with exotic materials like titanium and graphite. Club heads were enlarged and perimeter-weighted to provide a bigger sweet-spot, and square grooves increased spin on the ball. Big-hitting modern pros like John Daly and Tiger Woods regularly crush the ball 400 yards and more, turning the feared classic courses of yesteryear into meek pitch-and-putt lambs. And once again, the purists were apoplectic at this heresy of technology.

In both tennis and golf, technology created forgiving tools for the players, enlarging the sweet-spot and reducing the negative effects of a mis-hit shot. Traction control is no different. By modulating the power delivered to the road wheels, traction control in effect creates a bigger throttle 'sweet-spot' for the drivers.

Naturally, the purists will be aghast, citing that Fangio, Moss and Nuvolari had no need for such artificial driving aids. But modern Formula One bears little resemblance to the sport practised in those halcyon days. For one thing, the legendary drivers of yesteryear were required to change gears manually, usually crash-changing without the aid of gearbox synchromesh. The modern driver is not even required to take one hand off the steering wheel, instead flipping a lever to change gears semi-automatically.

Naturally, the purists will be aghast, citing that Fangio, Moss and Nuvolari had no need for such artificial driving aids. But modern Formula One bears little resemblance to the sport practised in those halcyon days. For one thing, the legendary drivers of yesteryear were required to change gears manually, usually crash-changing without the aid of gearbox synchromesh. The modern driver is not even required to take one hand off the steering wheel, instead flipping a lever to change gears semi-automatically.

Clark and Co. had to learn throttle control, modulating the pedal as they went airborne at the 'Ring or Mosport, or risk blowing the engine from the resultant rev spike. Aerodynamic wings and rev limiters put paid to that aspect of driving skill. Modern-day drivers have endless technological aids and advancement to make their jobs easier. When Michael Schumacher suffered from an ailing engine at the 2000 Brazilian GP, Ferrari engineers were able to talk him round the track via radio, advising him how to minimise the problem. That was an aid which Fangio never enjoyed.

One of the major fears is that traction control will even out the differences in driving skill, allowing lesser drivers to compete on equal terms with the big guns. Nothing could be further from the truth. When traction control was allowed previously in 1993, did it rob Ayrton Senna of his legendary wet-weather advantage? Was Alain Prost's ultra-smooth style compromised? In both cases, the answer is a resounding 'no'. Those two dominated the sport, just as they had done before traction control.

Over-sized graphite tennis racquets didn't turn journeyman pros into Borg-beaters, nor did titanium shafts and two-piece golf balls allow weekend hackers to go out and shoot in the sixties at Augusta. It still required enormous talent, endless practice and fanatical dedication to succeed, and the cream inevitably rose to the top. The same will continue to apply in Formula One.

Technological innovations in tennis and golf were viable only because they were available to everyone, from weekend novice right up to the world's elite. And this is the most sane and pragmatic aspect of the FIA's traction control decision. Since 1994, there have been persistent rumours and cheating allegations, most of which have centred around traction control. However unproven, these allegations have harmed the sport's integrity, and it is time to create a level playing field for all contestants. Legalising traction control will end those allegations in one fell swoop.

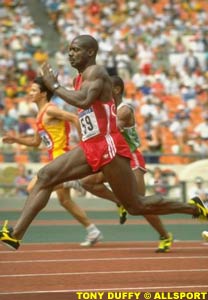

In that sense, the obvious parallel is with modern professional athletics. Only the terminally naive could believe that Ben Johnson was the only sprinter on steroids in that infamous 100m Seoul Olympic final in 1988. The Canadian sprinter's crime lay not in taking a banned substance. Instead, he committed the cardinal twentieth-century sin - he got caught in the act.

There is little doubt that many other athletes benefitted from steroids during that and subsequent Olympics. The sophistication of masking chemicals allows the cheaters to stay one step ahead of the Law. Again, there's an obvious parallel with F1. The ingenuity of software programmers has made it virtually impossible for the stewards to prove traction control allegations. As such, the rule is basically unenforceable.

There is little doubt that many other athletes benefitted from steroids during that and subsequent Olympics. The sophistication of masking chemicals allows the cheaters to stay one step ahead of the Law. Again, there's an obvious parallel with F1. The ingenuity of software programmers has made it virtually impossible for the stewards to prove traction control allegations. As such, the rule is basically unenforceable.

It would be difficult for an ostensibly healthy sport like athletics to legalise steroids. The chemicals may enhance performance, but at a price - potential heart problems, mood swings, and physiological changes are just three aspects of the downside. By contrast, traction control is not a health hazard, and should be allowed.

Ultimately, professional sports are not an end, but a means. Pro sports serve as a testing ground for innovations which ultimately filter down to the vast layman fan base. Such is the case with tennis and golf equipment, and many safety and engineering innovations pioneered in motor racing eventually became incorporated in standard road-going saloon cars.

Formula One should be about technical innovation, about brilliant designers and engineers pushing the envelope to go faster, further, better, cheaper. The restrictive current regulations mitigate against that. If the aim was to create parity in which a mega-budget team couldn't buy their way to the top, it's failed miserably. The last decade of F1 has provided the most one-sided racing in the sport's history - Williams, McLaren and Ferrari each taking turns to dominate.

With Ford, Toyota, Renault and Honda joining Mercedes and Fiat as the major corporate players, there will be no shortage of money in F1 for the immediate future. The sport doesn't need a narrow technological envelope in which the best Newey-clone design triumphs. It needs to open up the technological boundaries and embrace the sort of free-for-all innovation which marked the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies. Reversing the ban on traction control is a good way to start.